Working 'The Corner'

Neighbors and officials plan one more effort to save the neighborhood around 12th and Chicon

By Jordan Smith, Fri., July 13, 2012

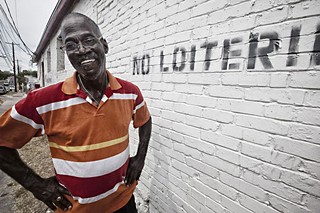

Lee Sherman was cleaning catfish in his backyard when he heard someone walking up the gravel path toward his neighbor's house. Sherman lives on New York Avenue, in Central East Austin, about a block south of the intersection of East 12th and Chicon streets, the city's most notorious corner for open-air drug dealing and the kind of crime – prostitution, burglary, assault – that a marketplace for addicts attracts. Sherman's neighbor's car had recently been broken into and his wife's gym bag full of clothes had been stolen. The neighbor asked Sherman if he'd keep an eye out – his wife was pregnant, her due date near, and the neighbor was vigilant about keeping her safe. Sherman agreed.

So on that Monday, Memorial Day 2011, Sherman looked up when he heard the footsteps next door; there was a woman walking toward the house. She was well-dressed and seemed to know where she was going. Sherman knew that his neighbor, a small-business owner, often worked from home and on occasion had employees drop by. The woman, he thought, was likely an employee. "The person was dressed pretty nicely and all, so I was like, whatever," Sherman recalls. "But I was watching and she walked through his gate and starts walking toward his car, and I had known that someone had broken into his car." Seconds later, Sherman heard his neighbor yell: "'Hey! What are you doing in my yard?'" Moments later, the wife chimed in: "'Those are my shoes!'" Sherman recalls hearing. "'And that's my shirt!'" The woman walking toward his neighbor's house was the same woman who'd broken into the neighbor's car, Sherman realized. "And now she's back, in broad daylight ... wearing the shoes, wearing the shirt."

Sherman heard his neighbor and the woman arguing; the neighbor didn't want to let the woman leave until the cops could get there, and the woman was not interested in sticking around. Sherman picked up his phone and dialed 911. The woman saw him, Sherman says, and started to panic; she tried to push past the neighbor, but "he wouldn't let her go." The two fell to the ground, and the neighbor started to yell: "Lee, help me out! She's biting!" Sherman ran over to help pull the woman off his neighbor. When he did, he saw blood "running down" his neighbor's chest; the woman, later identified as 47-year-old Cassandra Brooks, had bit him right through the nipple. When the police came, they found a crack pipe and assorted stolen items in Brooks' bag, Sherman recalls. "And they hauled her off to jail."

Roughly a month and a half later, Brooks was arrested again, just blocks to the north, for theft and possession of drug paraphernalia. Two months after that, she was picked up again, right at the corner of 12th and Chicon, for marijuana possession; less than a month later, she was popped once more, several blocks west of The Corner, for burglary. In all, between February 2007 and October 2011, Brooks was arrested 35 times, on 69 charges – including 11 cases of drug possession, six cases of theft, three cases of burglary of a vehicle, and two cases of prostitution – the vast majority of those arrests happening right around 12th and Chicon. Yet Brooks has been prosecuted just four times in the last five years, most recently for the October 2011 burglary, which netted her 12 months in jail, by far the longest sentence she received during that time period, according to court records. She has not been prosecuted for biting Sherman's neighbor.

Brooks has the kind of record that Sherman and many other residents near 12th and Chicon know all too well – and they're frustrated by the revolving door that they believe is a hallmark of criminal justice related to a corner where drug deals happen in the open and where people hang around hustling all day long – drinking, selling and using drugs, prostituting to earn money for their next fix. "It's like skid row," says Keri Slater, another neighbor just to the south, who has lived within a quarter-mile of 12th and Chicon for 11 years. "If you sit there for 10 minutes, you see drug deals in the middle of the day. It's known that this is where you come to get drugs."

The issues of crime and drugs at 12th and Chicon are not new; it is a place that criminal justice officials have long known as an open-air drug market bustling with associated crime, some of it violent. Veteran Austin Police officers and longtime residents say the culture of The Corner has been the same for nearly 40 years. Both old and new residents are tired of the crime and blight that the drug market brings with it, and they're frustrated that city and county officials have never made the kind of commitment to the neighborhood that it would take to clean up the area.

Few know this fight better than Scottie Ivory, who has lived three blocks from 12th and Chicon for more than 60 years. "It's the same thing" year in and year out, she says. "The real truth is that I don't feel like they" – anyone, really, from the police to elected city officials, she says – "care that much about it."

The frustration quickly seeps into any conversation about the possibility of real change at 12th and Chicon; even more problematic is that there is no real consensus about what it would take to make that change. Sherman and a group of residents have begun to press officials – primarily District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg and brass at the APD – for help cleaning up The Corner.

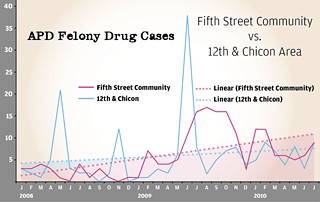

The latest push was largely prompted by the recent success in another part of town, using what is known as "enhanced prosecution" – a focused effort to deal swiftly and sternly with those responsible for drug and related crimes, and bringing maximum prosecution for repeat offenders, such as Brooks. Such an effort successfully shut down an open-air drug market that in 2009 had developed Downtown, along East Fifth Street (see "The 5th Street Posse"). That this tool and others – like the city's "no sit, no lie" ordinance that prohibits sleeping or sitting on sidewalks in certain parts of town – aren't being used at 12th and Chicon irritates Sherman and his neighbors. "If any area needs these tools, it's ours. So, at the end of the day, you look at 12th and Chicon and you don't have sit-lie ... you don't have enhanced prosecution," says Sherman. "We just don't have the kinds of tools that other problem areas have in place. And [can] you tell me why that is? I don't know exactly."

Whether enhanced prosecution (or sit-lie, for that matter) could work at 12th and Chicon is a matter of debate – and beyond that, the idea of rounding up and sending to prison every bad actor associated with that corner isn't universally appealing to neighbors or local officials. For too long, rounding people up – including many young, black males – was the only approach used at 12th and Chicon. It hasn't exactly had any lasting effect, except to brand a large number of people as felons, making it even harder for them to find a way off The Corner.

So the question facing neighbors and public officials remains: What would it take to clean up 12th and Chicon and improve the quality of life for everyone once and for all?

Weeding Without Seeding

There was a time when 12th and Chicon was at the center of the Eastside universe, a vibrant hub for the city's African-American community, a place where arts, commerce, and daily living fit seamlessly together. "We used to be self-sufficient in East Austin," says Ivory. "The only time we needed to go to Congress Avenue was to buy shoes or clothing." Those days are gone. Although the city finally got around to paving streets here in the late Sixties, many of the businesses began to close as the city moved to desegregate, and the old neighborhood began to lose cohesion.

Now, there isn't much left. There's a "prayer cafe" operated by the Mission: Possible! ministry, where, when volunteers are around and the place is open, a person can go and pray in exchange for a cup of coffee. There's a liquor store on Chicon, a small pool hall (rumored to host a robust backroom gambling operation) across the street, and a couple of clubs (including the Legendary White Swan) along the north side of East 12th on either side of Chicon. There are barber shops and Galloway's Sandwich Shop, just west of Sam's BBQ. There are plenty of people around, making the street look more prosperous than it is. And there is a sort of prosperity, if you include the drug dealers – some of whom live in the area, but many more come here to work, making a daily commute like thousands of other Austinites.

Indeed, the area does have a serious drug problem, say Austin police and many residents and other community stakeholders. Most of it operates in the open along both sides of Chicon, north of 12th Street, spilling into the alley between East 12th and 13th. People gather here in all weather and at all times of the day and night, selling or buying primarily crack cocaine and marijuana, says APD Sgt. Robert Jones, who supervises the Central East Metro Tactical Unit that leads most of the drug sting operations in the area. Jones has been working in this neighborhood for most of the 17 years he's been with APD, and he believes that although progress is slow, things have actually gotten better over that time. The open-air drug dealing and related crime, he says, "has decreased over time; however ... if I lived in that particular block, I would not be satisfied with the rate of change."

There have been many attempts to speed things up. For years police have done sting and long-term undercover drug operations here; they've netted many arrests but generated no long-term change. There was the Central East Austin Weed & Seed Initiative, a federally underwritten effort to reduce crime, improve social services and other community resources, and concentrate community policing efforts, in order to maintain police visibility and strengthen the community-police partnership.

Whether Weed & Seed had any positive effect on 12th and Chicon depends on whom you ask. There were plenty of "weeding" arrests, but not so much "seeding" – at least as Robert Love sees it. Love, a former addict who has worked with HIV-positive and drug-addicted people for nearly two decades, is quite familiar with the dynamics of 12th and Chicon, where he used to run the county mental health service agency's Community AIDS Resources and Education drop-in center a half-block north of The Corner. For five years, he and the CARE center were a resource for the drug users in the area, a place where they could come for HIV testing, drug-treatment referrals, a cup of coffee, a clean bathroom, and the friendly ear of someone like Love, who worked hard to get people off the corner by connecting them to the social services that would help them to do so. "We got a lot of people tested and into [drug] treatment and referrals" for other services, he says.

That ended, however, when Weed & Seed started. After a wrangle between the APD and the county's mental health provider (now Austin Travis County Integral Care), the drop-in center was shut down. "The [police] said we were attracting all the addicts, that we were part of the problem" at The Corner, Love recalls. Love strongly disagrees; the reason the drop-in center was located there, he insists, was because that's where the need was – and even after Weed & Seed burned out (the program was eliminated earlier this year), that's still true. "The issue there is they really don't have any services," Love says. "They get stuck on that corner and can't seem to get out of it." The CARE program moved to East Second Street, but the addicts from 12th and Chicon have not followed, Love says.

The policing statistics remain dispiriting. Consider this: In a recent three-week operation, Jones' officers arrested 35 individuals for drug dealing at 12th and Chicon; collectively, those 35 people had been charged with roughly 3,000 crimes over the course of their criminal careers. Whether any of them will be off the street for long isn't clear – even to Jones. "Repeat offenders are arrested on a regular basis," he says, cycling in and out of jail and back to the street, regardless of the severity of their offenses.

In a recent sting, one of Jones' officers bought drugs from a dealer on The Corner; when the cop went to arrest the man, he ran down the alley. Officers chased him and had to use a Taser to get him under control and arrested; the very next day, police caught him slinging dope again. After another undercover buy, the man again ran, this time fighting with officers before being taken into custody. "Is it frustrating? Very much so," says Jones. In 2011, police made a total of 610 arrests for 939 offenses at and around the intersection of 12th and Chicon; in the first six months of this year, they've made 251 arrests – including many of chronic offenders – for a total of 376 offenses.

The situation frustrates many neighbors, says Keri Slater. "I love my neighbors, I love my neighborhood. ... It's the most diverse place you can live in Austin," she says. "If [there were this many arrests] for drugs or prostitution in Hyde Park," something would be done, and quickly, she believes. "If somebody wanted to do something about [12th and Chicon], they would've [already]." Sherman and others point Downtown – there, when an open-air drug market took hold in 2009, neighbors rallied and D.A. Lehmberg responded, instituting the swift justice of enhanced prosecution to close down the dealing. If that approach is good for Downtown neighbors, he wonders, isn't it good for Central East neighbors too?

Finding Another Way

In December 2011, the Austin American-Statesman reported the success of the 5th Street Community project, and Lee Sherman took notice. He contacted community activist Madge Whistler, asking her if she thought that enhanced prosecution could work at 12th and Chicon and how, exactly, the Downtown neighbors achieved their goal of shutting down the open-air drug dealing so quickly. Work with your beat cops, Whistler told him – "because they're the people who are going to make a difference for you every night out" – and work with your neighbors. Those relationships, she says, were the keys to the project's success. And she told him she believed the success of the 5th Street Community would be replicable in neighborhoods all over the city.

However, a crucial difference in the Fifth Street and 12th and Chicon situations is the nature of the two neighborhoods and therefore the impact of the drug scene. Downtown, the dealers and their customers were almost exclusively considered outsiders by the residents, themselves mostly relative newcomers to the neighborhood. But 12th and Chicon is embedded in an Eastside neighborhood with a historically ambivalent relationship with police and public officials. The drug market itself includes both hardcore criminals and neighborhood residents caught up in the life for lack of other opportunities and resources. As a result, addressing the problem would seem to require both a more nuanced and more comprehensive approach than simply more arrests and prosecutions, "enhanced" or otherwise.

In that context, Lehmberg thinks there may be a better way to address the chronic problems at 12th and Chicon. She'd like to try the High Point Drug Market Intervention program developed in North Carolina (in part by former APD Assistant Chief Jim Fealy), which has been used across the country with impressive results. The Corner is "pretty clearly an open-air drug market. And you know, one of the things I've been told by so many people, including the police, is 'we have tried every initiative – we've had stings, we've had special operations, we've had everything,'" and yet the problems persist. "That's one of the reasons I started looking at the High Point solution, because it is specifically marketed [to combat] open-air drug dealing, and it has had a lot of success. ... I mean, there's nothing about High Point that isn't enhanced prosecution; it's just got a different name." And a different, more nuanced, approach.

What recently retired High Point, N.C., Police Chief Fealy knows about drug-law enforcement he learned as a cop in Austin (where he worked for nearly 30 years) and with the help of lifelong Eastside resident Scottie Ivory. In the late Eighties, when Fealy was in charge of mid- and street-level narcotics enforcement, he was approached by Ivory and her daughter. "They said, 'we're sick and tired'" of the open-air drug dealing at 12th and Chicon, "and we want you to do something about it." Fealy agreed and wanted to help, so he put together Operation Rock Crusher. "It was very secretive, and it went on for months and months," he recalls, culminating in 100 indictments, state and federal. "We arrested a lot of people," he says.

As soon as it was over, the criticism began, with a group of West Austin residents arguing that Rock Crusher was nothing more than another example of the APD "picking on a black neighborhood." Fealy was offended – and so was Ivory. She called a press conference and told reporters that the neighbors had asked for the help and that Westsiders should butt out. "When the cameras clicked off," Ivory turned to Fealy. "'Lieutenant, you guys are almost as bad as the drug dealers,'" he recalls her telling him; he was stunned. "I said, 'What do you mean?'"

Ivory asked if Fealy recognized her grandson – yes, he said – and if Fealy knew he wasn't a drug dealer. Yes, he knew that, he said. Then why, she wanted to know, was her grandson repeatedly harassed – "slammed" against cars, frisked, and regularly jacked up – during the drug operation? "You guys are unfocused," he recalls Ivory saying. If the cops had continued much longer with Rock Crusher, she told him, the neighbors would begin to wonder who the real bad guys were. The words stung, Fealy said, but he took them to heart.

Fealy says he had learned that traditional law enforcement actions, such as Rock Crusher, do nothing to end the open-air drug trade. "Not only is that approach not sustainable, but it gets the community to hate us." Thus, when he moved to North Carolina in 2002 to take over as chief of police in High Point, which at that time had a violent crime problem disproportionately high for its population of 107,000, he knew he needed to do something to shut down the city's five open-air drug markets, and that it would require an entirely different approach.

Fealy teamed up with David Kennedy, a professor and director of the Center for Crime Prevention and Control at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. Kennedy was well-known in law enforcement policy circles for his direction of the Boston Gun Project and as the designer of the gun-violence intervention model known as "Ceasefire," responsible for a 60% reduction of youth homicides in that city. Fealy and Kennedy adapted the Ceasefire strategy to an intervention designed to address open-air drug dealing, and then applied it to the entrenched drug markets of High Point, creating what is now nationally known as the High Point DMI.

The strategy is a radical departure from traditional policing methods. Essentially, it goes like this: Police identify the main drug dealers in an open-air market; for those truly bad actors, particularly dealers with histories of violence, police build cases in a traditional manner and prosecutors throw the book at them, taking them out of the picture and placing them behind bars – akin to straightforward enhanced prosecution.

But for the lower-level dealers, the endlessly replaceable ones, police build cases but stop short of filing them. Stakeholders – police, prosecutors, neighbors, and social service providers – work to identify a support structure for those dealers (a mother, grandmother, brother, or cousin) and then reach out to those people and to the dealers themselves. They're asked to attend a police "call-in," with the promise that the dealers will not be arrested. At the meeting, police lay it on the line: Cases have been built but not filed, the dealers are told, and they're given the choice to keep dealing – and have those cases filed and prosecuted to the full extent of the law – or get off the street now. If they choose the latter, the former dealers are offered the kind of wraparound services (job training and placement, for example, as well as drug treatment) that could help them start a new life.

In High Point, the initiative has reportedly been a rousing success. "It's redemptive. So many times the police and the community don't see eye to eye, but on this we could. We're working together like we never have in our lives," High Point Rev. James Summey said of the project in a report disseminated by the U.S. Department of Justice. "This is the most fantastic thing I have ever seen." The drug markets have closed, and many of the dealers have not reoffended. Moreover, data collected in High Point reflects that not only did the open-air markets close – they did not reappear in other parts of the city. In short order, High Point went from being one of the most dangerous cities in North Carolina to its second safest.

"Nobody believes it" will work when they first hear the DMI design, but it does work, Fealy says. Since retiring, Fealy has been consulting with cities across the country that have already implemented the DMI, or want to – among them Los Angeles, New Orleans, and now Austin, where he arrived this spring to deliver a presentation on the DMI to police, prosecutors, and neighbors. And local officials – including APD Chief Art Acevedo – say they're ready to give it a chance. "I am completely supportive" of the idea, he says. But, he notes, the neighbors are going to have to get in there and help to make it a success – much the way the Fifth Street neighbors dove in to work with police to drive the drug trade off their streets. "It is a shared responsibility. It can't just be us working our asses off."

A Tailored Approach

Although she hasn't ruled out any approaches, Lehmberg is increasingly convinced that some form of DMI is the best way to address the tensions between those neighbors who believe that only hard-nosed prosecution will end the lawlessness and those (including many longtime residents) who are wary of the kind of round-'em-up justice that's been employed in the past. Lehmberg says that specific tension became especially apparent to her during her recent long and tough primary campaign fight with former Judge Charlie Baird, and she believes the DMI is "tailored" to address the competing desires of residents. "There's always going to be some tension about who should go to prison. I feel like if you have someone who really displays a genuine interest in rehab, we owe it to them to try it."

Sherman would frankly prefer to see the enhanced prosecution program that aided Whistler and her Downtown neighbors, but he understands that the DMI better reflects the current neighborhood perspective, and he's cautiously optimistic that it could work. He's still frustrated, he says, that it's taken months of dogging the D.A.'s Office and other public officials in order to get them even to consider doing something. "Everybody knows [what goes on there]; it's no secret. So do something about it already," Sherman says. "It shouldn't be my responsibility to kick you in the ass. At the end of the day, I think those [problems] crop up in areas where people allow [it]. And I don't think that any area should allow it."

Ivory is equally frustrated by the problems at The Corner, but she's also quite skeptical of the motives of the folks who now seem so eager to fix things, and she thinks that the only reason there's any push to do so now is because of neighborhood gentrification. There is no doubt that Central East Austin is changing, and that eventually East 12th and the area around Chicon will change too. Indeed, APD's Sgt. Jones says that in his time working in East Austin, he's seen firsthand that "revitalization" encourages "long-term problem-solving." Consider the corner at East 11th and Lydia streets, he says, which once was a destination for homeless addicts and hosted an equally entrenched open-air drug market. Now it's a thriving corner, where cafes and condos have replaced empty lots and decrepit structures. (It remains true that neighbors still avidly debate whether the 11th Street development has sufficiently benefited longtime neighbors, or if it's mostly for the newcomers.)

Some change is already in store for 12th and Chicon, with the construction of a roughly 45-unit development of affordable, owner-occupied housing and ground-floor retail being built by the Chestnut Neighborhood Revitalization Corporation, an affordable housing non-profit that bought several lots along Chicon between East 12th and 14th streets. Demolition of existing structures is likely to happen by the end of the month, and Sean Garretson, CNRC president, says the units should be ready for move-in by fall 2013. "That was once a center of activity," he says. And now the CNRC wants to "help re-create that area."

That's one thing that everyone here has in common: a desire to see real and lasting change – though what that looks like, and how it can be accomplished, is still very much up in the air, a circumstance that will have to be solved if there's any hope for success. Nelson Linder, head of the Austin NAACP – its offices just west of 12th and Chicon – says he believes the DMI could work, but only if the other problems that have led to the long and complicated life of The Corner – and in the larger area – are solved as well. "Address poverty, education" and bring in jobs, he says. "You need a comprehensive approach." Sherman agrees, and says that everyone who cares about the future of the area needs to get involved. "We need some more leaders to step up and take the ball," he says. "If you care, you need to step up. You don't have to do it all, but you have to do something."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.