Working 'The Corner'

Neighbors and officials plan one more effort to save the neighborhood around 12th and Chicon

By Jordan Smith, Fri., July 13, 2012

(Page 3 of 3)

What recently retired High Point, N.C., Police Chief Fealy knows about drug-law enforcement he learned as a cop in Austin (where he worked for nearly 30 years) and with the help of lifelong Eastside resident Scottie Ivory. In the late Eighties, when Fealy was in charge of mid- and street-level narcotics enforcement, he was approached by Ivory and her daughter. "They said, 'we're sick and tired'" of the open-air drug dealing at 12th and Chicon, "and we want you to do something about it." Fealy agreed and wanted to help, so he put together Operation Rock Crusher. "It was very secretive, and it went on for months and months," he recalls, culminating in 100 indictments, state and federal. "We arrested a lot of people," he says.

As soon as it was over, the criticism began, with a group of West Austin residents arguing that Rock Crusher was nothing more than another example of the APD "picking on a black neighborhood." Fealy was offended – and so was Ivory. She called a press conference and told reporters that the neighbors had asked for the help and that Westsiders should butt out. "When the cameras clicked off," Ivory turned to Fealy. "'Lieutenant, you guys are almost as bad as the drug dealers,'" he recalls her telling him; he was stunned. "I said, 'What do you mean?'"

Ivory asked if Fealy recognized her grandson – yes, he said – and if Fealy knew he wasn't a drug dealer. Yes, he knew that, he said. Then why, she wanted to know, was her grandson repeatedly harassed – "slammed" against cars, frisked, and regularly jacked up – during the drug operation? "You guys are unfocused," he recalls Ivory saying. If the cops had continued much longer with Rock Crusher, she told him, the neighbors would begin to wonder who the real bad guys were. The words stung, Fealy said, but he took them to heart.

Fealy says he had learned that traditional law enforcement actions, such as Rock Crusher, do nothing to end the open-air drug trade. "Not only is that approach not sustainable, but it gets the community to hate us." Thus, when he moved to North Carolina in 2002 to take over as chief of police in High Point, which at that time had a violent crime problem disproportionately high for its population of 107,000, he knew he needed to do something to shut down the city's five open-air drug markets, and that it would require an entirely different approach.

Fealy teamed up with David Kennedy, a professor and director of the Center for Crime Prevention and Control at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. Kennedy was well-known in law enforcement policy circles for his direction of the Boston Gun Project and as the designer of the gun-violence intervention model known as "Ceasefire," responsible for a 60% reduction of youth homicides in that city. Fealy and Kennedy adapted the Ceasefire strategy to an intervention designed to address open-air drug dealing, and then applied it to the entrenched drug markets of High Point, creating what is now nationally known as the High Point DMI.

The strategy is a radical departure from traditional policing methods. Essentially, it goes like this: Police identify the main drug dealers in an open-air market; for those truly bad actors, particularly dealers with histories of violence, police build cases in a traditional manner and prosecutors throw the book at them, taking them out of the picture and placing them behind bars – akin to straightforward enhanced prosecution.

But for the lower-level dealers, the endlessly replaceable ones, police build cases but stop short of filing them. Stakeholders – police, prosecutors, neighbors, and social service providers – work to identify a support structure for those dealers (a mother, grandmother, brother, or cousin) and then reach out to those people and to the dealers themselves. They're asked to attend a police "call-in," with the promise that the dealers will not be arrested. At the meeting, police lay it on the line: Cases have been built but not filed, the dealers are told, and they're given the choice to keep dealing – and have those cases filed and prosecuted to the full extent of the law – or get off the street now. If they choose the latter, the former dealers are offered the kind of wraparound services (job training and placement, for example, as well as drug treatment) that could help them start a new life.

In High Point, the initiative has reportedly been a rousing success. "It's redemptive. So many times the police and the community don't see eye to eye, but on this we could. We're working together like we never have in our lives," High Point Rev. James Summey said of the project in a report disseminated by the U.S. Department of Justice. "This is the most fantastic thing I have ever seen." The drug markets have closed, and many of the dealers have not reoffended. Moreover, data collected in High Point reflects that not only did the open-air markets close – they did not reappear in other parts of the city. In short order, High Point went from being one of the most dangerous cities in North Carolina to its second safest.

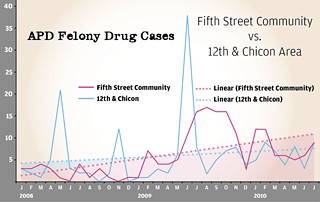

"Nobody believes it" will work when they first hear the DMI design, but it does work, Fealy says. Since retiring, Fealy has been consulting with cities across the country that have already implemented the DMI, or want to – among them Los Angeles, New Orleans, and now Austin, where he arrived this spring to deliver a presentation on the DMI to police, prosecutors, and neighbors. And local officials – including APD Chief Art Acevedo – say they're ready to give it a chance. "I am completely supportive" of the idea, he says. But, he notes, the neighbors are going to have to get in there and help to make it a success – much the way the Fifth Street neighbors dove in to work with police to drive the drug trade off their streets. "It is a shared responsibility. It can't just be us working our asses off."

A Tailored Approach

Although she hasn't ruled out any approaches, Lehmberg is increasingly convinced that some form of DMI is the best way to address the tensions between those neighbors who believe that only hard-nosed prosecution will end the lawlessness and those (including many longtime residents) who are wary of the kind of round-'em-up justice that's been employed in the past. Lehmberg says that specific tension became especially apparent to her during her recent long and tough primary campaign fight with former Judge Charlie Baird, and she believes the DMI is "tailored" to address the competing desires of residents. "There's always going to be some tension about who should go to prison. I feel like if you have someone who really displays a genuine interest in rehab, we owe it to them to try it."

Sherman would frankly prefer to see the enhanced prosecution program that aided Whistler and her Downtown neighbors, but he understands that the DMI better reflects the current neighborhood perspective, and he's cautiously optimistic that it could work. He's still frustrated, he says, that it's taken months of dogging the D.A.'s Office and other public officials in order to get them even to consider doing something. "Everybody knows [what goes on there]; it's no secret. So do something about it already," Sherman says. "It shouldn't be my responsibility to kick you in the ass. At the end of the day, I think those [problems] crop up in areas where people allow [it]. And I don't think that any area should allow it."

Ivory is equally frustrated by the problems at The Corner, but she's also quite skeptical of the motives of the folks who now seem so eager to fix things, and she thinks that the only reason there's any push to do so now is because of neighborhood gentrification. There is no doubt that Central East Austin is changing, and that eventually East 12th and the area around Chicon will change too. Indeed, APD's Sgt. Jones says that in his time working in East Austin, he's seen firsthand that "revitalization" encourages "long-term problem-solving." Consider the corner at East 11th and Lydia streets, he says, which once was a destination for homeless addicts and hosted an equally entrenched open-air drug market. Now it's a thriving corner, where cafes and condos have replaced empty lots and decrepit structures. (It remains true that neighbors still avidly debate whether the 11th Street development has sufficiently benefited longtime neighbors, or if it's mostly for the newcomers.)

Some change is already in store for 12th and Chicon, with the construction of a roughly 45-unit development of affordable, owner-occupied housing and ground-floor retail being built by the Chestnut Neighborhood Revitalization Corporation, an affordable housing non-profit that bought several lots along Chicon between East 12th and 14th streets. Demolition of existing structures is likely to happen by the end of the month, and Sean Garretson, CNRC president, says the units should be ready for move-in by fall 2013. "That was once a center of activity," he says. And now the CNRC wants to "help re-create that area."

That's one thing that everyone here has in common: a desire to see real and lasting change – though what that looks like, and how it can be accomplished, is still very much up in the air, a circumstance that will have to be solved if there's any hope for success. Nelson Linder, head of the Austin NAACP – its offices just west of 12th and Chicon – says he believes the DMI could work, but only if the other problems that have led to the long and complicated life of The Corner – and in the larger area – are solved as well. "Address poverty, education" and bring in jobs, he says. "You need a comprehensive approach." Sherman agrees, and says that everyone who cares about the future of the area needs to get involved. "We need some more leaders to step up and take the ball," he says. "If you care, you need to step up. You don't have to do it all, but you have to do something."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.