APD's Sleep Disorder

Detective Amy Lynch was a highly praised veteran officer – until she told her bosses she'd been diagnosed with narcolepsy

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Aug. 24, 2012

(Page 2 of 3)

The Diagnosis

Finally, in late 2009, Lynch was diagnosed with narcolepsy – a chronic condition marked by excessive daytime sleepiness, irregular nighttime sleep, and some degree of cataplexy – a sudden loss of muscle power, often "in response to emotion, usually humor," says Mali Einen, the clinical research coordinator at the Stanford School of Medicine's Center for Narcolepsy. Stanford researchers have demonstrated that narcolepsy is actually an autoimmune disorder, akin to juvenile diabetes, in which the body has erroneously destroyed a specific group of cells; in the case of narcolepsy, those cells produce the hormone hypocretin, which promotes wakefulness. There is no cure, but the disease is manageable with medicine and often with accommodations, such as scheduled naps. Because narcolepsy is generally diagnosed later in life – beginning in late adolescence – sufferers, like Lynch (and Einen herself), have often been branded as lazy or become frustrated with their perceived shortcomings long before they learn of their condition. "I do think it is largely misunderstood," says Einen. "People think, 'Well, I'm sleepy too, I know what narcolepsy is,'" but "falling asleep during a meeting or while watching TV" is not narcolepsy, she says.

When Lynch was diagnosed, she was surprised and relieved; it seemed to explain all her symptoms. (Lynch does not suffer from full-body cataplexy – wherein sufferers are momentarily paralyzed but fully aware of what's going on around them – but she does exhibit milder symptoms, including a drooping left eyelid.)

She immediately told her colleagues – "I was stunned [at] the diagnosis and ... didn't know anything about narcolepsy," she wrote in a recent email. "I definitely wasn't ashamed of it though; I was so relieved to put a name to what had been going on [with] me." And, she says, at the time she felt OK about sharing the diagnosis with her colleagues. Indeed, Lynch believes she is not the only member of APD who suffers from a sleep disorder. In a study reported in the December 2011 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, researchers found that 40% of nearly 5,000 cops studied suffer from at least one sleep disorder. Roughly a third suffer with sleep apnea; 7% suffer from severe insomnia. Nearly 30% reported "excessive sleepiness," and nearly half reported having fallen asleep while driving.

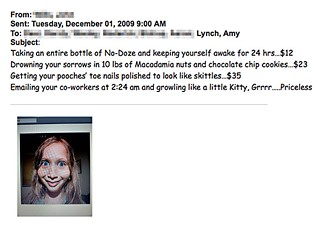

In retrospect, Lynch believes her disclosure might've been a mistake. After emailing a colleague late one night that she would be late to work because of sleep difficulties, she arrived the next day to find a snarky email in her inbox, addressed to her and three other colleagues. The email, which included the distorted face of a woman – her mouth in a wide closed-lip smile, her eyes bulging out of their sockets – parodied MasterCard's "priceless" ad campaign in several lines of text: "Taking an entire bottle of No-Doze and keeping yourself awake for 24 hours ... $12; Drowning your sorrows in 10 lbs of Macadamia nuts and chocolate chip cookies ... $23; Getting your pooch's toe nails polished to look like skittles ... $35; Emailing your co-workers at 2:24 am and growling like a little Kitty, Grrrr ... Priceless."

The Doctors in OCD

In spring 2010, Lynch was called into a meeting with Fuentes, veteran supervisor Sgt. Jesse Vasquez (now retired, but who then oversaw one of the OCD narcotics squads), and Cmdr. Chris Noble. She was being transferred to Vasquez's narcs team – a move considered "voluntary," she was told, a way for her to get out of the "hostile work environment" that she'd complained about. She agreed to the transfer, though she wasn't exactly thrilled about the idea of being pushed onto another team instead of being selected after applying for the job. And the move did not make things better. For starters, while she was happy to have the narcolepsy diagnosis, getting settled on the proper medication and dosage was difficult, and she endured a string of med changes and complications from side effects, while her symptoms persisted and continued affecting her work.

Among those who seem to have misunderstood her diagnosis was her new supervisor, Vasquez. When Lynch requested several days off to stabilize her medication, instead of sending her to the department's human resources folks to get her signed up for Family and Medical Leave Act benefits (which she and her attorney, Greg Placzek, believe he was required to do), Vasquez instead notified the APD's Risk Management Division, and attempted his own diagnosis. In June 2010, he wrote to Noble to explain that the supervisors in RMD had requested a memo regarding Lynch, as it would "be important to address the issue of documentation concerning Det. Lynch's statements concerning the disease of Narcolepsy" (emphasis in original). Vasquez went online to "briefly research" the chronic disease, which he defined only as excessive sleepiness. "Amy has been under my supervision only for a few months and in that time period I have not observed Detective Lynch to exhibit any of the signs of Narcolepsy."

Lynch says that Vasquez had her under a microscope throughout 2010. He texted her while she was off work and on vacation out of state; at one point he called her doctor on the doctor's private cell phone number, she says (how he got the number, she does not know), to inquire about Lynch's medical status and narcolepsy diagnosis. When Lynch found out, she was livid and complained about the violation of privacy; you brought it on yourself, she says she was told.

As Lynch recounts it, that was the attitude of everyone in her chain of command as she struggled to get her medical condition under control while attempting to remain focused and determined at work. By the end of 2010, Lynch was facing reassignment within OCD to the Firearms Review Unit, under then-Sgt. Patrick Connor.

Connor initially agreed to allow Lynch to arrive at 10am instead of 9am (a change she explained as a way to avoid commuting traffic), but he soon rescinded approval and eventually told her he would need her to come in at 8am instead – so that he could better monitor her work, he wrote in a series of notes he made about Lynch while she was assigned to his unit.

By mid-March 2011, Lynch was at her wit's end. She had been told repeatedly by her supervisors that her work was inadequate – most directly in an audio-recorded meeting with Connor and the rest of her chain of command, during which she was given a litany of examples of how she'd screwed up investigations and had been generally unreliable. Although the allegations were serious, they were never made the subject of a formal complaint for Internal Affairs; rather, it seems Connor kept notes regarding her shortcomings which were then detailed in the meeting. Lynch says she was blindsided by the weight of the allegations and unprepared to defend herself.

Lynch believed that her issues in OCD, including with Connor, could be explained by her medical issues and the department's misunderstanding of them. At the end of March, Lynch filed for extended leave under the FMLA, and when that ran out, for long-term disability. Both were approved. But when she eventually was ready to return to work – her physical symptoms had been stabilized – she learned that the department was, in essence, done with her.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.