Two Schools of Thought

Austin Community College and Austin ISD face board elections and distinct institutional challenges

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., April 30, 2004

Two boards, two educational systems, two sets of challenges – on May 15, voters will choose trustees for the boards of Austin ISD and Austin Community College in two coinciding but very different elections. The AISD board (see p.28) is, by most accounts, an agreeable place to hammer out the headaches in managing the underfunded 107-campus system, and the mostly uncontested races to fill four of the positions of the nine-member board reflect this steadiness. (They may also reflect the increasing public and financial pressures on what are essentially pro bono, unpaid positions.)

On the other hand, there will be two new trustees at ACC, where the board has endured an acrimonious and often grueling two years. Six candidates are competing for the seats of two members who opted not to run for re-election; only board Chair Rafael Quintanilla chose to weather another term, and he's running unopposed.

But even should both boards become paragons of political harmony and civilized debate, Austin's rampant growth combined with generally flat or decreasing state and federal support means that neither group – or institution – has an easy road ahead.

ACC: Collegiality, Accreditation – and Money

Whichever of the six candidates win the two open slots on the nine-member ACC board, where all seats are elected at-large, they'll have to keep one thing in mind: In recent years the job, with rare interruptions of accomplishment, has been very difficult. While the current board has made great strides in the last year in addressing many chronic woes, matters will still be at least somewhat sticky for the trustees who will step into the shoes vacated by Beverly Watts Davis (Place 4) and Beverly Silas (Place 5).

In 2003, the highs were particularly high and the lows very low for ACC, a seven-campus college with a $111 million budget. The Legislature, as it did to every state agency last year, cut community-college allocations by 7% (in midyear, doubling the effect) as well as cutting health benefits to part-time employees, exacerbating two previous years of budget shortfalls. Later, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, the accreditation agency for community colleges, took the college to task for improperly credentialed teachers and for what they described as too much direct trustee meddling in more properly administrative affairs. Two weeks ago, SACS again cited ACC on the credentialing issue, and the administration is scrambling to respond.

On a positive note, despite the college's acknowledged problems, in May of last year voters passed a $99 million bond initiative for capital improvements and a second proposition allowing trustees to raise property taxes, which they did by 2.7 cents, to 7.7 cents per $100 of assessed value. (The state average for community colleges is 15 cents.) The college also raised tuition by $3 per credit hour – a move actually endorsed by the student government. The financial boosts allow the college to begin digging out of its overall financial predicament, to give faculty a 3.5% raise, and to offer health benefits to some adjunct faculty who met specific criteria. Finally, the resignation of Richard Fonté – announced prior to last year's bond election – whose relations with the board and staff were notoriously acrimonious, cleared the way (and the air) for the board to offer the job last week to Robert Aguero, a vice-chancellor in the Dallas Community College system. (At press time, Aguero had not yet accepted.)

In the coming months, though, the board will face fresh challenges that the budget increases and the fresh administrative faces will not directly resolve.

First, there is the accreditation issue – endangered accreditation in theory threatens the credentials of every student who might enroll at the college. ACC will face a SACS review in September, in hopes of removing the school from the list of those on the agency's "warning" status. The board must show it has learned from the March 2003 SACS report that cited trustees for improper meddling in personnel and other administrative matters. But teacher credentials are the real problem. SACS wants teachers of degree-earning courses to have either a graduate degree or 18 hours of grad coursework in the subjects they teach. SACS allows exceptions for professionals – for example, allowing an undegreed IT professional to teach a computer course – but ACC hired 145 of its 1,600 faculty under such exceptions, and the agency wants ACC to be more restrictive with the exceptions.

If SACS refuses to compromise, the college may have to dismiss some faculty and move others among courses or departments. (In some cases, administrators may just need to confirm that the proper transcripts and documents are in teachers' files; faculty have complained that the human resources department occasionally loses transcripts.)

Another urgent issue is growth. Last spring's tax-rate increase is designed to keep ACC afloat, not to accommodate future growth. But a state-mandated "Closing the Gaps" initiative to make higher education more accessible set the goal of bringing an additional 500,000 Texans into higher education by 2015, and ACC should expect to serve 10,000 of those, a one-third increase over its current student body of 29,000 college-credit students.

Closing the access gap will require closing the funding gap. Currently ACC receives about a third of its funding each from the state, student tuition, and local taxes. Since those sources are largely static, the most realistic option is to expand the number of people ACC can tax within its wide-ranging service area. Currently, only three of the 30 school districts in ACC's area – Austin, Manor, and Leander – pay taxes to ACC; convincing other areas to join the college district is thus of paramount concern.

As a first step, voters in Del Valle ISD will vote in May on whether or not to join ACC's taxing district. That would mean a $70 annual property-tax increase for the average Del Valle homeowner, but it would give Del Valle residents, many of whom live literally across the street from the ACC Riverside campus, the right to pay in-district tuition – a savings of $1,560 a year for a full-time student. All the current board candidates agree that passing this Del Valle initiative – and others down the line – is vital to increasing revenues.

Furthermore, many faculty remain unhappy with ACC's pay scale, since a raise granted last fall only began to address the board's declared goal of bringing ACC salaries up to the state average over three years. "People say, 'Oh, you got this big raise last year,' but they forget that we hadn't been getting them for many years," says faculty senate President Daniel Traverso. "If we're the excellent faculty that state data shows and the board likes to tout, we would like to be paid better than just average."

Another issue is health benefits for the two-thirds of ACC teachers classified as adjunct professors, meaning (in theory) that they teach part time. "The people I feel sorry for are those who have been teaching a full-time load for years as adjuncts," said Caleb Buckley, president-elect of the adjunct faculty association, who plans to push for about $500,000 in the 2004 budget to extend health benefits to roughly 100 adjuncts who teach at least three courses a semester.

Several board candidates say ACC also needs to build additional bridges with AISD, where only three-fourths of high school students graduate, let alone pursue higher education. In May, ground will be broken on a new South Austin facility whose location was chosen in part for its proximity to Travis and Crockett high schools. "Having the campus right across the street from Crockett is one way to promote higher education for students for whom it isn't necessarily being promoted at home or in school," said Victor Rodriguez, an AISD parent who served on ACC's South Austin Campus Advisory Committee. "But there's more that can be done."

Rodriguez says ACC needs to do more to promote programs like Early College Start, a controversial program which allows high schoolers to earn high school and college credit simultaneously. This, says Rodriguez, will build expectations for – as well as ease the transition to – higher education.

Finally, the battles between ACC trustees, administrators, and employees have left wounds that are not totally healed. Buckley and Traverso say they are "optimistic," a sentiment now echoed by other college employees and officials. Whether that optimism is matched by positive action will in large part determine ACC's abilities to meet its numerous challenges.

AISD: Consensus Amid Looming Challenges

As ACC trustees look toward a fresh start, they might consider as a model the current incarnation of AISD, which over the last few years has generally moved from scandal and strife to harmony and stability. That's not to say that all is smooth sailing for the nine-member board that oversees 107 campuses and a $737 million budget. But as AISD trustees weather the winds of tight finances and demographic change, at least they're not beating each other with the oars as they move forward.

Two incumbents, Rudy Montoya (District 2) and Johna Edwards (District 3) are running unopposed. In District 5, Ingrid Taylor is stepping down, and community volunteer Mark Williams is the only candidate for her slot. In the at-large Place 8, Vice-President Doyle Valdez is being challenged by perennial Austin candidate Jennifer Gale, who has run unsuccessfully for at least 15 public offices in as many years and whom Valdez easily defeated in 1998.

The immediate challenge for AISD trustees is settling on the details, and then building support for a $420 million bond package to fund capital improvements that is expected to go before voters this fall. Pending voter approval, the bond issue, the first since 1996, would fix many of AISD's older buildings, suffering from age and long-deferred maintenance. The colonies of portables jamming campuses in the South, Southwest, and Northeast neighborhoods would be replaced with actual buildings – five new elementaries and one new middle school. The bond will also improve sports facilities and add new safety equipment, in part a reaction to the 2003 murder of Ortralla Mosley at Reagan High.

But passing the bond is only the first hurdle. AISD cannot raise property taxes beyond its current rate of $1.50 per $100 of assessed value, so barring a dramatic increase in revenue coming out of the Lege's special session on school finance (like a vision of piglets aflight over Town Lake), budgeting will continue to require funding one worthy program only at the expense of others. Teachers, in particular, feel they have been getting the short end of the stick. In the 2003 budget, they ended up with a de facto pay cut (all employees got a $410 raise but lost $500 in health benefits), which they hope the district will remedy this year. Trustees say that developing a compensation package will include the understanding that "compensation" includes nonfinancial factors like health benefits and working environment, but that won't satisfy everyone.

"We are very concerned about intermingling wages, hours, and working conditions," said Bruce Banner of Education Austin, the union representing most AISD employees. "It's not like they can say, 'Oh, we'll give you a 1 percent pay raise, but we'll give you a card on your birthday.'"

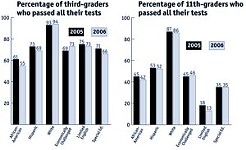

State accountability requirements also impose challenges, particularly on low-performing schools. To ensure that district schools all pass state tests, the administration implemented its own set of benchmark tests, weekly ones at low-performing schools. This system is designed to ensure that teachers can tailor their lessons to those test questions that students are not yet mastering, and by some measures is yielding results. This year, 91% of AISD third-graders passed the TAKS in reading, compared to last year's 86%. But many wonder if such gains in test scores come at too high a cost. Critics say that students would benefit more from a rich and varied curriculum that teaches thinking rather than memorization; they also say teacher turnover and the dropout rate go up under this system. (Despite improvement in recent years, AISD's high school four-year completion rate remains just 75%.)

"Kids who are not completing high school are the ones who are not doing well," said Don Loving, executive director of Communities in Schools, a nonprofit devoted to dropout prevention. "So there's this high emphasis on test results, which stresses kids out, and we can't give them the counseling and extra supportive services they need because it takes away from test prep time."

And looming over all that is demographic change. More students are living in outlying areas of the district, and more students are bilingual. The number of immigrant students, most of whose first language is Spanish, has doubled in the last five years, to 5,017 students.

Despite all these challenges, most observers heap praise upon the board and Superintendent Pat Forgione for facing their dilemmas and inevitable conflicts with an attitude of cooperation and open communication. Education Austin President Louis Malfaro acknowledges that the mostly uncontested May races reflect the board's success.

"I love a contested election because I think it's good for democracy," said Malfaro. "But I don't see any significant constituency that's unhappy with the job the board is doing."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.