CodeNEXT Wrecks Austin

Or did Austin wreck CodeNEXT?

By Sarah Marloff, Fri., May 25, 2018

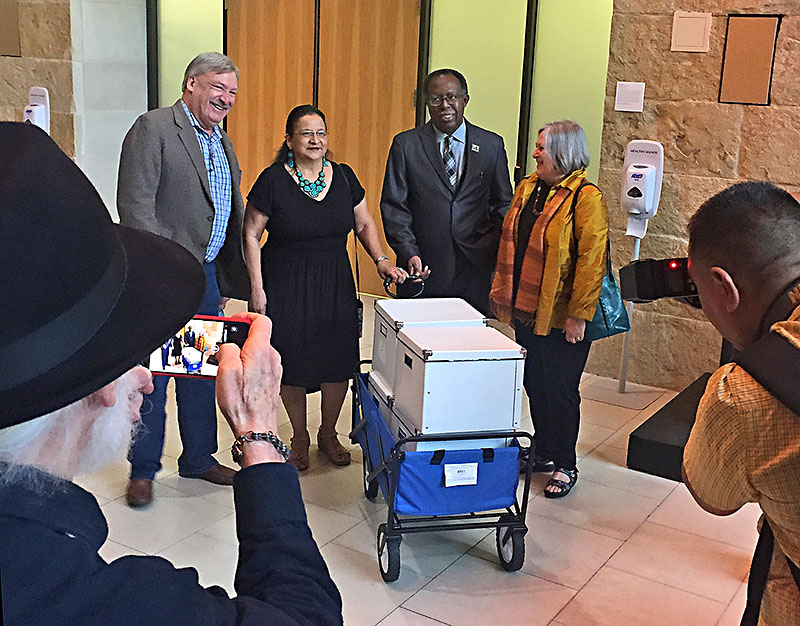

CodeNEXT's delivery to City Council is now imminent; the body's deliberations begin with the first of two public hearings this week. And after six years, three drafts (well, three and a half), $8.5 million spent, and three project leads, too many people have cast off hope for the zoning project.

But pay attention to that word: "project." Because when we talk about CodeNEXT, we're talking about a project. CodeNEXT, as an endeavor, concerns local zoning laws and regulations; its intention is to modernize those laws, and in the process evolve into the "compact and connected" city idealized in the Imagine Austin comprehensive plan. But CodeNEXT is not the code itself. It is the process of that code, its schedule and checkpoints on the road map. And after all this time, and all this money, and all this talk, it's becoming obvious that no part of the next few months will go to plan.

Drive through the city today and you'll spot "CodeNEXT Wrecks Austin" signs staked into neighborhood lawns. It's an overstatement, sure, but evidence of how low support for the rewrite has been since the first draft was released last January. That support has only diminished over the past 16 months. Even hopeful holdouts like Zoning & Platting Commission Vice Chair Jim Duncan have grown disillusioned with the process. In March, Duncan, a nationally renowned planner who oversaw implementation of the current code in the Eighties, declared the third and final draft to be "the worst code I have ever seen."

Duncan's rejection was perhaps the final straw for the land use commission on which he sits – one of two charged with reviewing the rewrite, and drafting recommendations for City Council. ZAP's commissioners have grown increasingly frustrated over the last several months, and on May 9 voted 7-4 to recommend Council "immediately terminate the CodeNEXT project." A damning indictment of the beleaguered endeavor, but not one the commission appears to be alone in making. Between election petitions and legal challenges, anti-CodeNEXT troupe Community Not Commodity has done what it can to shut down the project. Former City Council Member Laura Morrison is also campaigning for mayor on an anti-CodeNEXT platform, which she's accused of "making things worse" for the city. Following February's release of the final draft, the Austin Neighborhoods Council called the proposed language a significant threat to Austin homeowners, a "disaster for neighborhoods," and a "giveaway to large land developers." Social justice nonprofit PODER has accused the rewrite of furthering Austin's legacy of "racism in land development planning" by intensifying East Austin development.

And yet CodeNEXT continues, with plans now for Council to host their forums on Tuesday, May 29, and Saturday, June 2. Meanwhile, ZAP finds itself in uncharted territory: Following their recommendation, staff pulled the commission's standing agenda item from their May 15 meeting, believing ZAP had washed its hands. But the commission's officers say that's not true. Included within their recommendation was an alternative: Council does away with CodeNEXT and refocuses its efforts on fixing the "top 10" problems in the city's current code. The agenda item got reinstated for their next meeting, June 5, after staff, the mayor, and Council received a barrage of emails from angry commissioners.

It's uncertain how ZAP's input will be received, but the city's Land Use Commissions Liaison Andrew Rivera confirmed that if ZAP provides additional recommendations, staff will still forward their feedback to the city clerk, who disseminates them to the mayor and Council.

A messy situation, but it's only the beginning.

Getting to Today

CodeNEXT was born from Imagine Austin, the city's 30-year comprehensive plan, adopted by Council in 2012. The plan envisions a city that is at once inclusive, safe, livable, affordable, accessible, engaged, and healthy. The zoning rewrite is one of IA's eight core projects, and should lay the groundwork for the city to achieve its long-term goals in the places where the current code falls short.

Today's code, which determines what can be built and where, was adopted in the Eighties, when the city's population was under half of today's, at around 447,000 people. Consultants have repeatedly explained that Austin's current zoning is not designed to handle its growth rate (at about 2.9%, one of the fastest in the U.S.). The outdated code contains hundreds of amendments and an overabundance of conditional overlays, a tool to restrict land use by providing standards tailored to individual properties combined with the base zoning; there are roughly 4,000 of these in effect.

Consultants say those overlays are too often used because the current base zoning doesn't provide appropriate restrictions on its own. It's "patchwork," said ZAP Commissioner Sunil Lavani. Frequent users of the code say it's all but unnavigable to a layperson looking to pull a permit for anything from a new build to a small addition.

Civil engineer Mike Wilson told me that our current code was designed largely for greenfield, or undeveloped land. Today, Austin has almost run out of greenfield space. "Maybe it made sense in the Eighties," said Planning Commissioner Greg Anderson, but not for the city's future. Eric Bramlett, founder of Bramlett Residential Real Estate, with a background in residential development, called the code unnecessarily complex. He recalled one instance of a recent project in Pemberton Heights, where his team had to submit two sets of plans to the city after the first set was rejected due to a specific overlay having to do with garage setbacks buried within the code. According to Lavani, the development and permitting process has gotten worse "even in the last three years."

That's an unfortunate timeline, considering the Zucker Report that was also released three years ago. The report was produced by California's Zucker Systems following its biting analysis of Austin's Planning & Development Review Department. It identified a laundry list of issues that plagued the since-reorganized office. (PDRD split into two: Planning and Zoning, the department responsible for CodeNEXT, and Development Services.) Zucker slammed PDRD for overdocumenting "everything." It cited "no overall strategy to address employee concerns," and "no clear focus on customer service" – indeed, a customer survey yielded the most negative scores the group had seen in all its studies – and a "lack of clear and effective management."

Which leads to another area of CodeNEXT concern: One of Austin's biggest undertakings in decades has ultimately been overseen by the same department that received such low marks from Zucker. Wilson, though he's unhappy with the status quo, also doesn't believe the proposed code will improve current conditions. Both he and Bramlett say staff are partially responsible for the inefficiencies because the code is "coupled with the process." In Wilson's experience, much of the permitting process is subject to whichever staff member is reviewing it. Bramlett concurs, citing the remodel of his Allandale home: A framing inspector instructed him to pass the plumbing and electrical inspection first, but once that was completed another inspector informed him the first was wrong and delayed the project by a month.

Greg Guernsey, director of the Planning and Zoning Department, began his career as a city planner three decades ago in Austin. Prior to heading PAZ, he oversaw PDRD. Meanwhile, CodeNEXT's other lead staffers, Jerry Rusthoven and Jorge Rousselin, have been with the department for years, long before the Zucker Report. Duncan harbors concerns that the department, responsible for many of the ongoing code amendments, hasn't improved since the Zucker release: CodeNEXT, he said during ZAP's May 9 meeting, was developed by the "same people who created" the "mess" we have today.

ZAP's recommendation argued that the problems highlighted in the 2015 report remain overlooked and unaddressed. In an emailed response, staff cited a two-year progress report, updated last September, tracking which of the 418 "action steps" have been addressed and what has been subject to budget constraints. It documents what's been accomplished – such as hiring additional staff and plans in the works, and what could not be achieved, including hiring "contract staff" to help clear the city's site plan backlog. According to the progress report, Austin's current code is "too complex" to hire temps to review applications.

As for CodeNEXT, staff have been grappling with a massive amount of feedback. Over 2,500 comments were made on draft two's text and map, and as of May 11, an additional 600 on draft three. Guernsey admits that many people are making "very good points," and concedes the new code won't leave everybody content.

"We had an open house on Feb. 12 for draft three's release," he said. "One person told me how happy he was about the new ADU [accessory dwelling unit] flexibility, and reduced parking requirements.

"Then two people later told me I was going to bring all their neighborhoods down by allowing ADUs in neighborhoods by bringing in renters and clogging streets. And that's a pretty simple topic."

Public Hearings, Public Fears

"After two days of public hearings it was clear that there is minimal community support for CodeNEXT."

That's the opening line from ZAP's recent call for termination. About 150 residents spoke at those two hearings, set up by the land use commissions. (The Planning Commission held a third, on May 22, that was attended by four people.) Neighborhood preservationists in particular came out against the new code, which they believe is too appealing to developers. It wouldn't protect landowners, they said, and would displace the city's less fortunate. One woman brought several handwritten notes from her East Austin mailbox. "Hello, I'm interested in buying your home," read one. The phone number was from Los Angeles. She said notes like that were commonly found on her block.

But those who wish to see neighborhood change occur also raised concern with displacement and housing shortages. Members of AURA and Friends of Austin Neighborhoods worried that the code wouldn't go far enough in providing the amount and diversity of housing needed to keep Austinites living within the city. Many, arguing for greater upzoning of central neighborhoods, insisted it's a supply and demand issue: more development will bring in more housing. Others cited gentrification as a cause of drastic change.

The two conflicting opinions have been ongoing, and often spoken past each other – enough so that Stephen Oliver, who chairs the Planning Commission, recently wondered to me whether two wrongs for once make a right. If urbanists are upset because the proposed zoning is too similar to what we have today, and preservationists think there's too much change, "does that mean that it's actually somewhere in the middle?"

Does Oliver have a point? Guernsey said, "That's up to the commissions and Council to decide." (And one of those three bodies already has.) Guernsey is city staff, so he's going to be guarded, but he did make clear: Despite the boundless opposition, the city's land use code still needs a thorough revision. The proposed code, he insists, is "a far improvement from what we have today."

Fixing What's Been Broke

If the land use commissions' public hearings made anything clear, it's that the city has cozied itself into an unenviable situation: a simultaneous need to plan for and manage the city's rapid growth while protecting some semblance of the status quo.

CodeNEXT has become the scapegoat for both sides' fears. But the effort can also be the city's savior. The rewrite has been burdened with the impossible task of fixing everything from affordability to flooding to gentrification to transportation. While each issue represents a real concern deserving city attention, a land use code – especially in Texas – can only do so much. The state prohibits rent control, affordable housing linkage fees, and inclusionary zoning, the tools other states rely on to guarantee low-income housing and retain long-term residents.

Preservationists are calling for limited change, or "managed growth," as Laura Morrison puts it, specifically within the city's core. Even in the final quarter of the process, many are still suggesting small area plans be used to gradually implement code changes rather than remapping the entire city in one fell swoop. (Though a May 11 memo Guernsey sent to Council attempted to dash that hope: With the department's existing resources, he said, Planning and Zoning can complete about one to two small area plans a year, meaning it would take roughly 50 years to complete a full enactment of the new code.)

Meanwhile, urbanists demand higher housing density, and believe that's the only way to meet Austin's growing housing shortage, lessen traffic woes, and perhaps decrease the city's reliance on cars. CodeNEXT, aside from simplifying the current code and embarking upon developing an Austin that the city has imagined, is tasked with helping to create 135,000 housing units – 60,000 of which must be affordable – before 2028, under the city's Strategic Housing Blueprint. Each draft of the code has tried to increase housing capacity. The second upzoned a swath of the city's core to infill mostly single-family neighborhoods with missing-middle housing, but Guernsey said that raised "a lot of concern" that the rewrite put too much strain on central neighborhoods.

The current draft takes some of that pressure off neighborhoods and pushes the bulk of new housing density to the corridors defined by Imagine Austin. The reshuffle angered those fighting for more housing and a greater diversity of units, and put Guernsey in an "uncomfortable" position: Developers are complaining that the corridors, now zoned mixed-use, don't offer enough incentives or transition into neighborhoods, while residential property owners maintain that code will decimate certain areas of the city.

So no one's truly happy. Following draft three's release, the Statesman suggested that the draft "might give a sigh of relief to neighborhood activists," but naturally there was clapback: ANC accused the daily of not reading the lengthy draft, and said it poses "significant threats" to homeowners, renters, and businesses within the city's neighborhoods. Meanwhile, urbanist group Friends of Hyde Park argued the exact opposite, claiming draft three will force new development into already gentrifying neighborhoods, increase rents and intensify the city's housing shortage by limiting housing supply while demand is at an all-time high, and encourage "environmentally damaging sprawl."

It's the proverbial rock-and-hard-place deal, and no one seems to know the best way to move forward. ZAP stands by its recommendation to terminate the whole process, but that doesn't mean they want to withdraw from the conversation. Commissioners have reaffirmed their commitment to finding the "best possible regulatory tool" for implementing Imagine Austin, and the commission hopes to "identify and shape" their proposal in the coming weeks.

The Planning Commission, meanwhile, remains committed to forming their own detailed recommendations, which we can expect to be both long and (they hope) completed this Friday, May 25. When all is said and done, PC will have held seven meetings since May 1, totaling nearly 60 hours. Unlike ZAP, PC has generally been more supportive of the rewrite. Commissioners have offered and attempted to tackle nearly 1,000 draft amendments. Those that have been approved will form the body's recommendations, which state law requires Council to consider before moving forward.

Kick It To Council

Council officially begins CodeNEXT deliberations on Tuesday, May 29, via the first of two public forums. This week, during a work session on Tuesday, PAZ proposed members spend June 5 and 12 discussing the draft, and to consider June 13 and 21 for first reading. Those dates will be considered at the Council meeting today, but Mayor Steve Adler has already said he hopes to spend June digging into the "thorniest" issues of the rewrite to work toward a consensus. Adler has suggested not setting dates for first, second, or third readings; and to instead "talk at the end of June as to what happens next."

Council has yet to hold official discussions on the rewrite, though through discourse and a few proxy wars, the battle lines may already be drawn, with Greg Casar, Delia Garza, Pio Renteria, and Jimmy Flannigan favoring density and diversity of housing, and Mayor Pro Tem Kathie Tovo and colleagues Alison Alter, Leslie Pool, and Ora Houston taking a more preservationist approach. Casar, Garza, and Renteria have spent part of the past months pushing the Housing Justice Agenda, which they believe can slow displacement, while the latter four have sponsored a resolution on today's agenda that would direct the city manager to prepare draft language for any necessary ordinances, actions, and approvals necessary to put Community Not Commodity's petition onto the November ballot.

Standing between the two factions are Mayor Adler, Ann Kitchen, and Ellen Troxclair (currently on maternity leave), three of Council's six members (along with Tovo, Houston, and Renteria) who are up for re-election in the fall. Mayor Adler, ever searching for some compromise, has already drawn his ideological antithesis in candidate Laura Morrison, though opponents mounting challenges against the five CMs haven't been as outspoken against their incumbents' zoning ideals. But one can bet that if CodeNEXT extends into election season – and here's betting it will – each race will in some form serve as a referendum on the rewrite.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.