Cold as ICE

Sheriff Greg Hamilton stoutly defends the 'Secure Communities' deportation mill. But growing public and official opposition is working to shut down the line.

By Tony Cantú, Fri., July 4, 2014

Immigrant rights advocates keep a running tally.

There's Carmen, whose husband was deported last February, leaving her to care for and support a 3-year-old son and 15-year-old daughter by cleaning houses; her daughter suffers from depression, and after her father's deportation, attempted suicide. There's the married couple reported by neighbors for a loud argument, nonviolent but leading to the husband's arrest for domestic abuse and, ultimately, his deportation, leaving his wife to work two jobs to support the household. There's Margarita Campos, mother of two, stopped and detained for driving 10 miles an hour over the limit, already overwhelmed by the imminent deportation of her husband – following his own minor traffic violation, he was found to be undocumented.

These are among the proliferating narratives of those ensnared by the county's Secure Communities program – "S-Comm," as it is familiarly known – established by the Department of Homeland Security to help enforce U.S. immigration law. The initiative is designed to identify and hold deportable detainees in the U.S., with participating law enforcement officials submitting fingerprints of detainees not only to FBI criminal databases (as has long been standard practice), but also to immigration databases. The information-sharing enables Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials access to information on detainees and gives them 48 hours to assume custody – yielding a technological if not physical presence for ICE in America's prisons and jails.

DHS and ICE remain convinced of the program's usefulness in protecting homeland security and in deporting undocumented immigrants – even if those immigrants have lived peacefully and productively in the U.S. for many years, and even if they've been apprehended for an otherwise minor infraction. But public support for S-Comm – including, or even particularly, in Austin – is waning.

Austin's Chief of Police, Art Acevedo, dislikes the program; local immigrant rights advocates have galvanized in opposition; and throughout the country, acknowledging the potential for human rights and constitutional violations, once enthusiastic S-Comm participants are dropping their voluntary compliance.

On Thursday, City Council moved to have the city of Austin join the growing list of jurisdictions opting out of the program. Council members voted unanimously to approve a resolution aimed at convincing the sheriff's department to stop using the program, which has become a deportation launching pad for detainees arrested for even minor infractions. (Margarita Campos was among those who recounted to the Council the program's collateral human damage.)

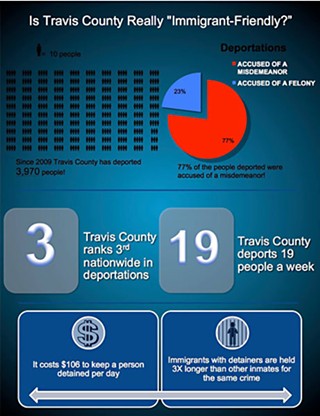

But Travis Co. Sheriff Greg Hamilton, responsible for operating the program, remains its staunchest local supporter, justifying compliance – effectively deporting an average of 19 people a week – with questionable data and unpersuasive arguments. He dismisses the widespread criticism of S-Comm, insisting on the program's necessity and legality. "My job is to ensure that the community as a whole is safe," he said during a recent interview. "People need to know who's in their community." Following up on last week's City Council action, Travis County Commissioners have announced that they're working on their own resolution asking Hamilton to pull out of the program, though it's unclear what effect even that would have, because the sheriff is an independently elected official who doesn't directly answer to the Commissioners (see "Hamilton Digs In: Won't End 'S-Comm.'"

The Sheriff's Defense

Secure Communities was piloted in 2008, with a $200 million congressional appropriation and 14 jurisdictions initially recruited as participants; fiscal years 2008-11 brought $750 million more. By March 2011, the program had expanded to more than 1,200 jurisdictions; ICE now is able to include all 3,181 jurisdictions – states, counties, jails, and prisons. Travis County joined in 2009.

Since signing on to S-Comm, Travis County has grown to be one of the nation's most prolific participants. Aggressive implementation by the sheriff's office – resulting in almost 5,000 deportations since 2009, establishing that average of 19 per week – has created a division in the community: Supporters cheer the program for weeding out criminals, while immigrant rights advocates decry the collateral damage to families as well as the corollary threats to constitutional rights.

Designed, in theory, to accomplish the laudable goal of identifying serious felons for deportation, S-Comm has devolved into a wide-ranging dragnet apparently motivated more by immigrant complexion than reasonable suspicion of criminal wrongdoing. More often than not, civil libertarians say, the county's burgeoning Hispanic population is effectively targeted. Motorists stopped for "driving while brown" for something as incidental as a broken taillight enter the gateway for a full-fledged, ICE-sanctioned review for documentation. Immigrants' rights advocates estimate that nearly 75% of the detainers in the last two years were issued for people who had never been convicted of any crime.

It was this "broken taillight" scenario – in fact a reality for at least some detainees – that opened a recent phone conversation with Sheriff Hamilton. He doesn't buy it. "The troubling aspect is, that is the mantra being used across the country," he said of the broken taillight tale. "That's a national mantra of some of these groups out there. I'm not saying it happens, or doesn't happen, but I've never arrested someone for a broken taillight. When people talk about people being deported for minor offenses or Class C misdemeanors – they might have gotten a ticket for a broken taillight, but there are more offenses there than a broken light."

Sheriff Hamilton then asks, "Are you at your computer?" Moments later, a list of detainees on "Immigration and Naturalization Service" detainers who have been held in the Travis County jail arrives in my inbox. The list appears to be a Who's Who of serious criminals, detainees incarcerated for heinous crimes: aggravated sexual assault of a child; aggravated assault with a deadly weapon; murder; driving while intoxicated (several); terroristic threat of family/household; improper photography or visual recording; arson. There are dozens on the list, recounting a chilling litany of crimes.

Yet on further review, the list yields more questions than answers about S-Comm as it is practiced in Travis County. For one thing, the detainees are not listed by name, nor are their countries of origin provided, making it impossible to tell which minority group is most targeted. Then there's that anachronistic "INS detainer" assigned to each inmate, rather than an ICE detention that would more precisely reflect S-Comm.

In the post-9/11 world, the INS no longer exists. In March 2003, INS functions were placed under three agencies with the then-newly created DHS: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; Immigration and Customs Enforcement; and Customs and Border Protection. Given such inconsistencies and omissions, Hamilton's list doesn't make the case for S-Comm's success. It is instead a nameless roll call of those currently incarcerated – but in fact doesn't demonstrate whether these criminals had been taken off the streets thanks to the workings of S-Comm.

Asked if the list in fact is a compilation of those captured as part of S-Comm – "No," Sheriff Hamilton responds via email. "As I have explained in our telephone conversation, the reason for the list was to show you the seriousness of the crimes that people with ICE detainers are being arrested for in Travis County." So is Travis County safer because of S-Comm? Or does the list of those apprehended by traditional law enforcement reflect that S-Comm is in fact extraneous?

Indeed, the sheriff acknowledged, there's no comparable list for those detained solely under S-Comm. Absent such a list, could he point to hardened criminals who have been taken off the streets thanks to S-Comm? On the phone, his answer was speculative, touching on the criminal element that could – in principle – be targeted through S-Comm. He cites a handful of horrific examples of cases involving people initially placed on ICE detainers but released before adjudication, only to later commit heinous crimes: a detainee released who later killed a mother and her daughter; another detained on a DWI charge who later killed a family on the highway; another detainee released only to learn he murdered his girlfriend.

As it turns out, however, none of those crimes actually occurred in Travis County. Perhaps nearby in Texas? Had Hamilton said "Caldwell County"? "The examples I told you about were from Cook County, Illinois, not Caldwell County," the sheriff writes in an email clarification. Unasked, he adds helpfully, "All County Jails in Texas honor ICE Detainers."

When I first spoke to the sheriff in May, I asked him about a recent ruling by the U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals – that federal detainer requests are in fact not mandatory, as Hamilton had previously insisted. He responded that the 3rd Circuit is a northeastern court; the 5th Circuit has jurisdiction over Texas. Yet the examples of serious crimes associated with S-Comm detainees he offered were from Illinois. I referenced the growing list of cities and counties pulling out of S-Comm as further evidence of its disfavor: Arlington; Va.; Baltimore; Berkeley; Chicago; New York City; Philadelphia; Newark; New Orleans; Washington, D.C.; Alameda, San Diego, and Santa Clara counties in California. All told, some 112 jurisdictions and counting have opted out of participating in S-Comm, either by refusing ICE detainer requests without subpoenas or through the enactment of resolutions or ordinances. In rebuttal, the sheriff had provided the "INS detainer" list.

Amelia Ruiz Fischer, an attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project, said she's familiar with Hamilton's list of dangerous felons with "INS detainers." She said the sheriff started providing the list earlier this year, after immigrant rights groups called for more transparency.

"That list is bullshit," she says, and "disingenuous." She said TCRP's statistician reviewed it and found further flaws. For one thing, she says, the window of time during which the tallies are taken – at 6am during recording days – doesn't allow for the brief time some S-Comm detainees are held before being subjected to ICE deportation proceedings, leaving those detainees off the list. That inevitably weights the list toward those held for longer periods.

"He only started gathering the data after our protest in April," Ruiz Fischer continues. "You look at the time he's gathering it – of course people who are going to be there on a daily basis, held on the more serious charges, are the ones that are going to appear. The person who is there every day is used as a tally, or a percentage point, for every day. Some people are in one day and gone the next, so that person only gets one tally. ... That's going to make the people there longer counted more [often]."

Thus, she says, the count is skewed toward the arrestees held for longer periods because of an inability to post bond – due to the severity of the crimes for which they were initially apprehended, unrelated to their immigration status. Consequently, it sheds little or no light on the effectiveness of the S-Comm program in Travis County – ostensibly practiced to weed out the worst offenders. Moreover, it does not address at all the human toll of family separation often spurred by arrests for minor charges nonetheless submitted into the whirlwind of the federal deportation system.

Acevedo Weighs In

Austin Police Chief Art Acevedo isn't a fan of S-Comm; in an interview, he described the fear and distrust it creates in the Hispanic community. Many opt not to report crimes, creating a roadblock for his officers, he said. Acevedo believes the matter should be addressed through national immigration reform – which could include an updated bracero (guest worker) program – rather than programs like S-Comm, which only serve to alienate and marginalize entire communities. In a May meeting with President Barack Obama and other national officials, he expressed his hopes for reform, under the auspices of Bibles, Badges, and Business for Immigration Reform, a national network of faith, law enforcement, and business leaders. "Immigration reform is almost universally supported by law enforcement, the clergy, and the American people," he said at the gathering. "The time to act is now."

Returning after that D.C. meeting, he expressed his disapproval of the program in general and its lack of transparency in particular. "No one is providing data to prove or disprove who is being deported," he said – although he was reluctant to criticize Sheriff Hamilton directly. "I talk to the sheriff on who ICE is putting a detainer on, and he does not see anyone being detained who is not one of two things: a violent criminal, or someone engaged in a pattern of serious offenses, including burglary of habitation. He has yet to see anyone in jail not there for anything less than a serious offense."

But when pressed, Acevedo acknowledged he's never actually seen tangible data from Hamilton. "I take it at his word," he said. "I've never had a reason to mistrust him."

Rights Violations, High Costs

Alejandro Caceres, co-executive director of the Austin Immigrant Rights Coalition, believes S-Comm procedures violate the U.S. Constitution; he says the 48-hour hold on detainees to check immigration status appears to violate the Fourth and 10th Amendments. "They're violating people's constitutional rights when incarcerating people," he said. "It's like holding them for another charge, but without due process or reasonable suspicion."

Moreover, advocates point out, the hold sometimes goes beyond the official 48 hours, as weekends and holidays aren't counted. Cities closer to the border with a robust ICE presence (such as San Antonio) typically discharge detainees more quickly. In Travis County, a minimum 48-hour hold is a foregone conclusion, as jailers wait for immigration officials to become available to pick up detainees. Immigrants who have arrived seeking work to support their families find themselves incarcerated for minor offenses and facing deportation – meanwhile languishing in detention. "Travis County is deporting people at a more alarming rate," Caceres said, "and it needs to be addressed immediately."

In its unyielding support of S-Comm, Caceres adds, the county opens itself up to legal liability, pointing to the growing list of detainer-related lawsuits in other municipalities. Arguably the most prominent case was filed in February 2012 against the Connecticut Department of Corrections, for holding individuals solely on the basis of unexpired immigration detainers.

Hamilton is unmoved. "Once someone has told me that it is a violation of the Constitution, then we will take a real close look at that," he responded. "But I don't know anyone that has said definitely that's a violation."

Caceres and the AIRC are calling for an immediate end to S-Comm. "This program has caused enough damage in Travis County. What we need to do is continue to value our immigrants' rights, and everything they've done for Travis County." S-Comm opponents question the value of deporting a head of household for reasons of immigration status, leading not only to human suffering among separated family members, but also to additional drains on taxpayer money, as families must avail themselves of social services and emergency rooms in order to stay alive.

And that's just the tip of the financial iceberg. Noralba De La Rosa of the Austin Immigrant Rights Coalition notes that Travis County is not reimbursed by the federal government for the full cost of honoring ICE detainers. Instead, the feds only partially reimburse the county jail for costs associated with detaining certain immigrant arrestees, through the Department of Justice State Criminal Alien Assistance Program. SCAAP covers only correctional officer salary costs, and restricts the types of inmates it will credit the county for reimbursement.

According to figures compiled by the AIRC and other advocacy groups, in fiscal year 2008 the county's housing of ICE detainees – detained amid immigration questions prior to the county's formal participation in S-Comm – cost $1,313,862. Using county data, the AIRC learned that 3,094 people were held in the Travis County Jail with ICE detainers in 2011, with an average stay of 32.03 days (versus the average stay of 13.06 days among those without a detainer). Those extended, ICE-fueled stays translated into an additional 58,693 jail days, at a personnel cost of $60.59 per day. The upshot: ICE detainers created an additional detention cost of $3,556,220 for the fiscal year. SCAAP reimbursed $683,501.

Hamilton's Isolation

Chief Acevedo agreed that the cost to run the program is antithetical to running a detention center. "We don't need another unfunded mandate," he said of S-Comm. "It's counterintuitive." Hamilton didn't dispute the numbers, but says they reflect expected costs of running a jail. "There is a cost for public safety," he said, citing examples when inmates are held for extended stays for myriad reasons. "No one talks about that. The 48 hours could be held up, but many are removed the same day."

Hamilton argues he is required by law to comply with Secure Communities. But that federal appeals court has ruled otherwise, and other jurisdictions have begun to leave the program. Last Thursday, Austin joined the ranks of those jurisdictions attempting to leave the program. In a 7-0 vote, Council members passed a resolution aimed at forcing the sheriff from exercising the S-Comm effort so aggressively. The resolution has three aims: opposing the use of Travis County resources for the implementation of the S-Comm program; urging the Travis County Sheriff's Office to stop complying with ICE detainers by holding people in its jail targeted for ICE custody; and directing the city manager to research options to minimize or completely replace the city of Austin's use of the Travis County Booking Facility (a significant source of the jail's income) until such time S-Comm participation is terminated.

City Manager Marc Ott will report to the Public Health and Human Services Council Committee and the Joint Public Safety Working Group prior to delivering a formal report to Council in the next 90 days.

In a morning press conference ahead of the Council vote, Council Member and resolution sponsor Laura Morrison said, "It takes a toll on broken families, it erodes trust in law enforcement and policing efforts, it's costing the taxpayers, and it's not an effective mechanism for taking serious criminals off the streets."

Even the DHS has acknowledged that the program has not been carefully rolled out or precisely administered, as concluded in a March 2012 report by the Office of Inspector General. "We did not find evidence that ICE intentionally misled the public or states and local jurisdictions during implantation of Secure Communities," investigators wrote. "However, ICE did not clearly communicate to stakeholders the intent of Secure Communities and their expected participation. This lack of clarity was evident in its strategic plan, its outreach efforts, memorandums of agreement signed by states, and its responses to inquiries regarding participation."

Moreover, investigators found, ICE leadership failed in its guidance efforts to participating jurisdictions. "ICE senior leadership also missed opportunities to provide clear direction to its officials implementing Secure Communities," the report states. "As a result, 3 years after implementation began, Secure Communities continues to face opposition, criticism, and resistance in some locations."

In its own April 2012 report, ICE addressed the issue of detention priorities. "ICE agrees that felons should be a higher priority than misdemeanants and civil immigration law violators, although certain serious misdemeanants and egregious civil immigration law violators are priorities as well," wrote ICE officials. "The Civil Enforcement Priorities memorandum states that ICE's top enforcement priority includes aliens convicted of crimes, with higher priority given to individuals convicted of more serious crimes. The memorandum also states that some misdemeanors are relatively minor and do not warrant the same degree of focus as others, and that ICE agents and officers should exercise particular discretion when dealing with minor traffic offenses such as driving without a license."

To a person, immigrants' rights advocates have voiced support for weeding out serious offenders, even if they are found within the minority communities they represent. But for those on the front lines in defense of immigrant rights, deportation seems not just reserved for hardened felons, but for all undocumented immigrants captured as part of S-Comm, regardless of the severity of their transgressions.

Sheriff Hamilton remains unmoved. Despite growing opposition to S-Comm, he remains the initiative's most ardent local supporter. While even fellow law enforcement officials condemn the practice, he champions it. "The one person who has the power to change it is the sheriff," Caceres said. "And he's dug in his heels."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.