AISD High Schools Flunk Real-World Test

Audit says district poorly prepares grads for college or careers

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., Oct. 22, 2004

If a good friend is one who is honest about your faults, then AISD has no better friend than the Southern Regional Education Board, which last week issued a less-than-rosy audit – commissioned by AISD – of the district's ability to prepare its graduates for college and careers. The solutions the SREB offered will shape several months of discussion and planning in the AISD community – and then the future of AISD high schools.

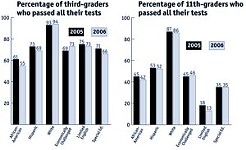

First, the bad news. According to the SREB, too many ninth-graders aren't ready for high school; four years later those same students aren't prepared for college. Ninth-grade failure rates are "disturbingly high," with 34% failing Algebra I, 62% failing physics/chemistry, 29% failing biology, and 25% failing English. Most students take as little math as possible; current career and technology offerings are for the most part "extremely poor in quality." AISD's 11 high schools are too big and impersonal. And, in a finding that would shock many an Austin teenager ... too much of high school is irrelevant to the real world.

The SREB argues that AISD can turn things around – the key is breaking big high schools down into smaller, career-focused institutes. While all AISD high schools have some career education courses, in areas like communications and business, the district has only two full-fledged career institutes (according to AISD's career and technology education head Mark Kincaid): culinary arts at Travis and health services at Lanier.

The SREB report argues that AISD needs more such institutes – done properly, they tie academic subjects to real-world applications, prepare students for higher education or industry certification, and make high schools less impersonal. However, they require a total school overhaul. "There are some really neat things in these reports," said Bowie HS principal Kent Ewing at the SREB's report presentation. "There are some things that make you quake."

The SREB audit suggested the district group its students into career concentrations, with a target ratio of 20% of students in a math/science concentration, 20% to 30% in the humanities, and the rest in more tightly focused career and technical programs. Such groupings, he argued, enable schools to better tailor academic classes to real-world applications, and vice versa. Currently, he explained, academic subjects like biology or math are taught as self-contained bubbles with no real-world application – as in a traditional math class that consists primarily of abstract drills. "That's good enough to pass the test on Friday, but not to teach you reasoning skills," said the SREB's Gene Bottoms.

On the other hand, students in a well-defined concentration like health services could focus on health-related projects in English or math class; at the same time, their teachers can incorporate reading and math activities into their health services classes. In this way, rigor is an across-the-board expectation, literacy and numeracy are reinforced, and students stay engaged. "When you take a kid's interest in a specialty area, and you find ways to connect it to the academic courses we all have to take, it makes education come alive," said Kincaid.

Plus, creating career groups breaks down large schools into the "smaller learning communities" that are all the rage in the educational world. AISD has already started SLC experiments in several high schools – Travis, for example, is already broken into several "houses" of around 350 students each, while some poor-performing students have blossomed after moving to Garza Independence HS, an alternative high school with fewer than 300 students. The idea is that students learn best when they know their teachers and their teachers know them – something that's impossible when teachers teach 120 different students each year – and the SREB encouraged AISD to keep moving in this direction.

Of course, the idea of turning AISD high school campuses into conglomerates of schools-within-schools is sure to meet some bumps. First, there's the issue of preparing students for diverse career paths while also preparing them for standardized tests, on which many AISD schools already underperform. This won't be a problem, argues AISD Associate Superintendent Rosalinda Hernandez, because the skills tested in the state TAKS tests are those students have to learn anyway. "The TAKS tests are essential for all students, so it doesn't make a difference what career pathway they're interested in," she said.

Another issue is that of pigeonholing students too early in life. On the benign end, this could just lead to confusion when a student who signs up for a culinary track in ninth grade realizes by her junior year that she really wants to be an investment banker. Kincaid says the institutes will plan for this kind of youthful exploration. "Everything will be driven by student interests," he said. "So if their decisions or directions change, we will have built-in flexibility."

A more troublesome take on the issue is that the institutes sound uncomfortably like the bad old days when "smart kids" took calculus and "dumb jocks" took shop. But Kincaid argues that the newest programs offer rigorous career preparation totally unknown to the generation for whom "tech ed" meant auto shop. Whether their focus is construction or math, he says, all students will receive an equally rigorous education. "The old blow-off, take-it-because-your-buddies-are-taking-it wood shop days are gone," he said. "Our career and technology curriculum has to be rigorous, and it has to be relevant. You don't get that building birdhouses."

The public will have numerous opportunities to comment on the planned redesign throughout the fall. The SREB audit, plus an additional report by UT researchers, is available on AISD's Web site, www.austin.isd.tenet.edu.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.