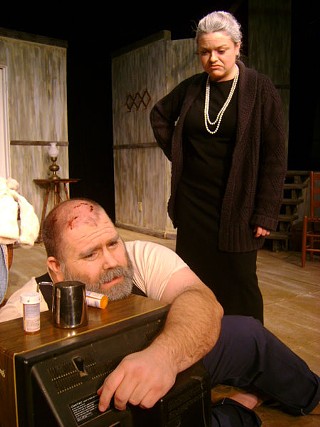

Buried Child

Despite rough edges, City Theatre's staging stays centered on the play's ideas

Reviewed by Elizabeth Cobbe, Fri., Feb. 19, 2010

Buried Child

City Theatre, 3823 Airport, 524-2870, www.citytheatreaustin.org

Through Feb. 21

Running time: 2 hr, 10 min

There are two ways to see Buried Child. Either you know the secret this family is attempting to conceal or you have to figure it out along the way. Everybody should experience Buried Child ignorant once, just to grasp the horror of it.

I've already had my first Buried Child experience, and seeing another production is like observing a freight train on its way into the side of a mountain – unless the production rises to the level of poetry, where the humor and balance built into the words and images keep the show from devolving into a crazy hate-fest. Under Caleb Straus' direction, City Theatre Company's Buried Child approaches that level of artistry, but it has much room to grow.

The script is part of a body of American literature built around what might be termed "the effed-up farm family." It's something that even the most citified among us relate to, given that most Americans are no more than a few generations removed from the farm. In this case, playwright Sam Shepard shows us how the incubator of the family farm – its isolation and the toughness it demands – has turned one family in on itself. The patriarch, Dodge (Wray Crawford, who spends much of the play hacking up a lung in character), is infantilized by poor health and his own resentfulness. His wife, Halie (Samantha Brewer, with an out-of-place Southern-ish accent), exudes a youthful energy that stems from a remarkable capacity for denial. Their grown sons, Bradley (Errich Peterson) and Tilden (Rod Mechem, at his best when he appears as a quiet, wounded animal), are damaged in ways both physical and emotional.

Then along comes Tilden's son Vince (Stephen Cruz) and Vince's girlfriend, Shelly (Keylee Paige Koop). Vince has been struck by a sudden urge to reconnect with his heritage, and poor Shelly comes along for the ride, only half-willingly. What happens next is like what you'd see if you were to throw solvent over a Norman Rockwell oil painting: Everything dissolves into a sad, ugly mess.

It's a play that is obsessed with manhood, fatherhood, and family memory. It's also a challenging play to direct. Each of the characters operates in his or her own world, and bringing all performances to the same level is not easily done. In this production, the cast is tuned to within a half-step of one another, but they haven't quite agreed on a common note.

It should also be said that the choice not to have Tilden ascend the staircase at the end is like watching Stanley whisper instead of yell "Stella!" It's expected that directors ignore most stage directions in a script, but that one's pretty central to how people remember the play.

Buried Child is a difficult play to produce, and it can be a difficult play to watch. Despite its rough edges, City Theatre's production succeeds in keeping the play centered around the troubling yet profound ideas at its core.