La Onda Chicano

Sunny Ozuna, still talking – to you, me, and Texicans everywhere

By Greg Beets, Fri., July 21, 2006

Despite the October demise of the city's last Tejano radio station ("Outlaw Onda," Music, February 17, 2006), the sticky-hot spring night of Saturday, April 22, unquestionably constituted a banner moment for Tejano music in Austin.

As the sun receded behind the UT Tower, thousands of Tejano fans filed into Bass Concert Hall for "Los Grandes de la Música Tejana." The gala concert brought "Little Joe" Hernández, Austin's Ruben Ramos, and Sunny Ozuna together on one bill to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the university's Center for Mexican-American Studies. Backed by an orquesta drawn from Hernández's La Familia and Ramos' Mexican Revolution, these three pioneers of "La Onda Chicana" broke ground once more by playing the first-ever Tejano concert at UT.

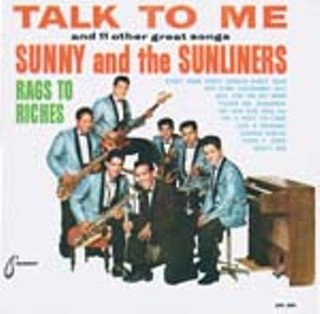

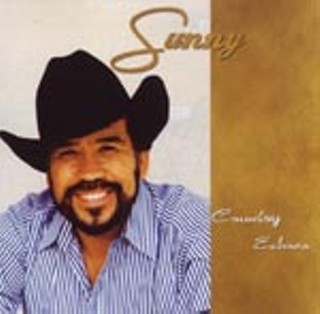

Show-opener Ozuna took to the stage dressed resplendently in a zoot suit and feather-topped fedora. Stomping off the tempo to begin each song, he wooed the excited crowd with fleshed-out renditions of romantic, proto-Tejano staples like "Cariño Nuevo," "Put Me in Jail," and, of course, his calling card, "Talk to Me."

Nearly 43 years after Sunny & the Sunglows hit with that Texas Top 40 classic ("Texas Top 40," Music, November 8, 2002), Ozuna shows no outward signs of slowing down. The gregarious 62-year-old performer still shuttles effortlessly between musical genres and concert circuits, using years of gauging the pulse of San Antonio dance floors to tailor his shows to the audience at hand.

"Tejano has turned out to be 150 percent dancers, man," Ozuna tells me after the show. "We are dancers! They can't stand to sit in one place. They're going crazy in the chairs. It's in their blood to want to get up and just tear up the dance floor. It's rough for them out there right now."

One of 12 children, Ildefonso Fraga Ozuna was born in 1943 on the south side of San Antonio. You might assume Ozuna became "Sunny" on account of his winning smile. In fact, "Sunny" evolved from "Bunny," his childhood nickname.

"I was real white when I was first born," Ozuna laughs. "I looked like a little white bunny rabbit. They didn't think I belonged!"

Against the backdrop of rock & roll's emergence, Ozuna formed his first garage combo in 1957 with future Latin Breed founder/sax player Rudy Guerra. The fledging act's earliest gigs were at school talent shows, carnivals, and the like. When they finally settled on a moniker that stuck, Ozuna got a new nickname out of the deal.

"I come from the 'and the' days," Ozuna says. "Little Anthony and the Imperials, Gary Lewis and the Playboys, Danny and the Juniors, that type of thing. Our very first little job was in Houston. I think we got $100 for it. We were on our way to Houston, and we saw a sign on the side of the road that said, 'Sunglow Feed Company.' We thought that sounded cool, but when it came to 'and the,' 'Bunny and the Sunglows' wasn't going to cut it."

San Antonio's rich intersection of musical tangents proved to be a perfect breeding ground for what would become known as Tejano music. One place Ozuna found inspiration was in Fats Domino's boogie-woogie piano triplets rolling down U.S. 90 out of New Orleans. The Fat Man's "Blueberry Hill" was also the first tune Ruben Ramos sang before an audience while still playing drums for his brother Alfonso's band.

"When we started, Ritchie Valens was big, Fats Domino was big, Elvis was big, and the Beatles were just getting started," Ozuna recalls. "In between all that, you had the doo-wop groups. So San Antonio became a lover of doo-wops.

"We had teenage shows that came on the radio in the afternoon after school. One was called Top Teen Tunes on KUKA. They mainly played Norteño music for the west side of town, but they played Top Teen Tunes in the afternoon. Most of the baby boomers that still support the music grew up with that teen show, and they all went to dances where local groups would cross a little conjunto with doo-wop and add Texas flavor to it."

Closer to home, Sunny & the Sunglows were also influenced by the big-band-flavored orquesta sound. "We all looked up to the Isidro Lopez Orquesta out of Corpus," Ozuna says. "His biggest competitor at that time was the Alfonso Ramos Orquesta, which was Ruben's brother. They had a full orchestra of 10 or 12 musicians and were doing the Benny Goodman-type orchestra.

"We were studying what they were doing, but they were going one step further than what we wanted to. We came up with something that was more like a combo. We were just kids out of high school, and we weren't equipped to do that, so we had a tenor sax, alto sax, and a trumpet doing a 1-3-5 harmony. That was a far as the horn section went."

Ozuna and the Sunglows released their first single, "Just a Moment," in 1959. Later that year, the group put out its first Spanish-language single, a version of Mexican composer José Alfredo Jiménez's "Pa, Todo El Año," on their own Sunglow imprint. 1962's "Golly Gee" was enough of a regional hit to warrant reissue on Columbia's OKeh subsidiary.

For the follow-up, Ozuna reached back to his childhood. Weekdays after school, the aspiring musico often hung out at the Palm Heights Recreation Center. While other kids played basketball and tennis, he was drawn to the piano, where future San Antonio R&B legend Randy Garibay repeatedly banged out a song called "Talk to Me" at Ozuna's insistence.

"It's amazing to me how he never thought of recording the song," Ozuna says of Garibay, who died of cancer in 2002. "He sounded just like Johnny Mathis. I think it's the way the Lord works, man. It just wasn't meant for him even though he had the song in his hands."

"Talk to Me" was written by Joe Seneca, a New York-based songwriter who later became a successful character actor, starring opposite Ralph Macchio in the 1986 Robert Johnson allegory Crossroads. Although Seneca's own version of "Talk to Me" didn't chart, Little Willie John's rendition was a Top 20 pop hit in 1958. Five years later, Sunny & the Sunglows took it higher, reaching No. 11 in Billboard after producer Huey P. Meaux released it on his Tear Drop label.

"I recorded 'Talk to Me' in a recording studio that's no longer there," Ozuna relates. "It was called Texas Sound Recording Studio. There was a gentleman, Jeff Smith, who owned this little studio. He never thought he would have such a big hit come out of his place. He was a beautiful man. He really helped us a lot."

By 1963, personnel changes prompted Ozuna to change the name of the Sunglows to the Sunliners. Meanwhile, he was still finishing his senior year at Burbank High School. "When the song took off, I went to my principal and said, 'Look, I'm just occupying space for somebody who really needs the education,'" he remembers. "Believe it or not, he gave me 21/2 credits for graduation."

The success of "Talk to Me" also garnered Ozuna a trip to Philadelphia, where he became the first Tejano performer to appear on Dick Clark's American Bandstand. Suddenly every kid in San Antonio knew who he was.

"All the kids weren't really up on what I was doing in high school," Ozuna chuckles. "They were into rock & roll, but this was all happening in the media and on the radio. They didn't really start paying attention until I got to American Bandstand. That's when everyone started saying, 'Yeah, this is my buddy!'"

Although "Talk to Me" was Ozuna's only Top 40 hit, his ability to fit comfortably alongside both José Alfredo Jiménez and Wilson Pickett served him well throughout the Sixties. The Sunliners could play "Brown-Eyed Soul" with the best of them, even backing Houston's Archie Bell & the Drells on "Dog Eat Dog," the flip side of "Tighten Up." By singing in both English and Spanish and embodying a variety of styles that made everyone want to dance, Sunny & the Sunliners helped build a template for an emerging new musical style.

"'Talk to Me' brought attention for what would now be known as Tejano music, but we didn't have a title for it," Ozuna says. "We were calling it, 'the Tex-Mex sound,' and 'Música Chicana.' Through the years it became Tejano music. It was music that expressed the feelings and emotions of people who lived in Texas. A lot of it still had accordion and a conjunto feel, but it was our version of what 'Tex-Mex' was going to be about.

"We gave the music a little more class. We did the big arrangements with the horns, a lot of keyboards, and a more modernized sound that went under the title of Tejano."

A few clicks up I-35 in Temple, Little Joe & the Latinaires were making a name for themselves with a similar sound, mixing rock, soul, and rancheras in small-town dance halls throughout the Southwest.

"We ran across Little Joe when we started working more outside of San Antonio," Ozuna says. "We wondered who they were and how it was possible that we were both doing something along the same lines. We played battle-of-the-bands shows with them and we packed them in.

"We kind of became friends, but we were also rivals. If he had something good, I would want to do it better, and if I had something good, he would want to do it better."

This late Sixties/early Seventies musical growth took place against the backdrop of the emerging Chicano Movement, hence the moniker, "La Onda Chicana." As the movement celebrated a cultural identity distinct from Anglo and Mexican culture, musicians like Ozuna and Hernández provided the soundtrack.

"As people from Texas, we wanted to relate to something," explains Ozuna. "Country does that for Anglos, but for Hispanics, we really didn't have anything we could say is us.

"So what Joe and I and people from our school tried to do was set these little rules for what we were all doing – knowingly or unknowingly – where we would put these different kinds of music together. Then we would work with the arrangements to reach a point where you'd say we were Texans playing Tejano."

Slowly but surely, Tejano became viable in an increasing number of markets outside Texas, a trend Ozuna attributes to migration coupled with word of mouth.

"A lot of Tejanos migrated to other states and promoted us without even knowing it," he says. "They would tell their friends about us and request our songs on the radio.

"Then we got to the day when we could go to all these places, but we were taking [monetary] beatings with overnight promoters. If I wasn't taking beatings, Little Joe was, so we tried to exchange information with each other about who to watch out for."

In between recordings and tours, Ozuna found time to appear in the 1974 Mexican film, La Muerte de Pancho Villa. He even did a morning drive-time stint on Houston's KYST-AM. "It was this little bitty AM station," Ozuna recalls, "but we were setting the world on fire."

It's not surprising to discover Ozuna has strong opinions regarding conglomerate-owned radio stations abandoning Tejano for regional Mexican music in a bid to increase listenership among recent immigrants. In addition to losing Tejano radio in Austin, key stations in Houston and Dallas/Fort Worth recently dropped the format as well. Having been there from the days when Tejano was only heard sporadically on the far upper reaches of the AM dial to when San Antonio's KXTN-FM became the first Tejano station to win a major-market Arbitron ratings book in 1997, Ozuna takes this shift personally.

"I don't want to sound prejudiced, man, I really don't, but I would've loved to see them come over here and become us," he says. "That would've been great. But I think what's going to happen eventually – and I hope I'm wrong – they're all going to come over here, and little by little, we're going to turn into them."

At the same time, Tejano music itself, which Ozuna tellingly refers to in the collective "we," doesn't escape blame for the current sad state of affairs. "In the mix of everything, we just kind of leveled out," Ozuna says. "Everybody was happy, everybody was comfortable, and everybody was working, but I don't feel like we were really growing anymore. We lost Selena, and nobody took her place."

Whatever happens to Tejano radio, Ozuna's genre-hopping career makes him remarkably resilient. If Tejano has a lull, he still has the English-language oldies circuit. "I still keep going back," he nods. "I go up and down the California coast five or six times a year with the rock & roll oldies shows. I was in Los Angeles in April doing something with Tower of Power."

Now signed to Corpus Christi-based Freddie Records, he won a Best Tejano Album Grammy in 2000 for ¿Qué Es Música Tejana?, by a Tejano "supergroup" called the Legends, featuring label namesake Freddie Martínez Sr., Carlos Guzman, and Augustin Ramirez. He's also branched out by recording both country and gospel.

Ozuna remains optimistic about the future of Tejano, pointing to sold-out hotel room blocks at last week's Tejano National Convention in Las Vegas as evidence of the genre's continued vitality.

"What we worry about is Texas because that's where we're from, but things have a way of working out," he observes. "Through all those years, I don't remember having a slump. Things have a way of coming back around.

"If the old-school is still standing, maybe we'll get another round." ![]()

Sunny Ozuna and Ruben Ramos double-team Antone's, Thursday, July 27.