Outlaw Onda

If you don't hear Tejano music on the radio, does it exist?

By Belinda Acosta, Fri., Feb. 17, 2006

When Austin's last Tejano radio station, KTXZ 1560AM, went off the air last October, there was a splatter of ink about it in the local press. The pieces ranged from measured obituaries to screeching demands like Julian Limon Fernandez's, which ran not once, but twice in Arriba Newspaper last December:

"Shame on you Univision and Border Music Productions! We are Tejanos and demand to be treated with respect!"

Dispassionate notices, raw anger – the truth rarely lies in the margins. Rather, it hides somewhere in the middle. Here's some of both.

The Honorary Chicano

Some say it was Chris Strachwitz's 1976 film Chulas Fronteras that first brought Tejano music and culture to a wider audience. Not that there hadn't been others. Before Chulas Fronteras, scholars like Oscar Lewis wrote scathing edicts about the pathology of being a mutt – neither Mexican nor American.

Instead, Chulas Frontera, like that famous fight scene from the movie Giant, spoke volumes about the Mexican-American experience in South Texas with few words. Strachwitz did something unheard of: He let Tejanos speak for themselves. Amazingly – considering the current state of our mediated culture – his gaze was deferential, unflinching, but not romanticizing.

Ultimately, Chulas Fronteras was about the music. It spoke to Strachwitz. Maybe not in the same way it spoke to Tejanos, but he felt that bite in his corazón, that yank of his tripas, or whatever it is that music seizes to create that harmonious flood of body, mind, and soul. Like being in love, it's intangible but undeniable.

Can Chris Strachwitz throw a grito? Can he barbecue cabrito? Does menudo cure his hangover? No importa. He met, and – this is important – he respected those musicians, those small-town deejays, those mom-and-pop record-label owners, and the others who didn't let the fact that their music didn't play on commercial radio stations convince them they didn't exist. Strachwitz met some of our musical antepasados and addressed them with respect. Just like we did.

Crossing Over

"The more conflict you have in a particular society during a particular period, the better the chances this conflict will find expression at the symbolic level, at the musical level, for example."

– Professor Manuel Peña in Héctor Galán's Songs of the Homeland

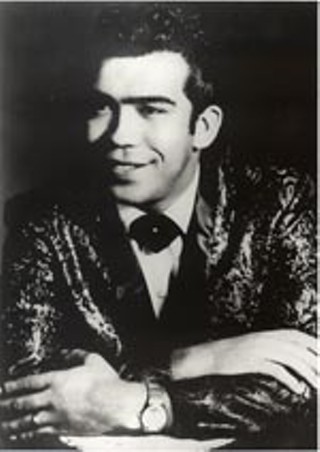

Photo courtesy of Hector Galan

Depending on what history book you read, Mexicans are here by mistake. In the 1970s, someone came up with the cry, "We didn't cross the border. The border crossed us." The heat in that line depends on the speaker and circumstances.

After World War II, when large numbers of Mexican-Americans served with valor, only to return to systemic racism back home, they knew things had to change. Laws were passed and inequities corrected, at least on paper, yet because the history of contact between Anglos and Mexicans in Texas is particularly violent, it led "to a unique and expressive Mexican/Chicano cultural response," writes Juan Tejeda in 2005's Conjunto (reviewed in the Chronicle, Dec. 2, 2005). "Conjunto music was created out of this conflict and is at once a resolution and a synthesis."

There are several lodestones in Tejano music history. Moments when we were "there," visible in the mainstream, if only for a moment, and then gone. At the same time these moments draw gasps of recognition they also provoke an awkward mourning, steeped in the historical experience that echoes – again and again – in the present.

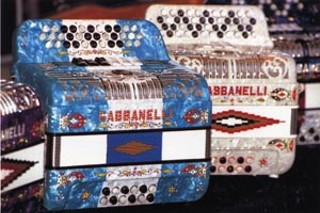

Early conjunto was music that evoked homeland and pride, a gentle reminder how much could be created with very little. At its most basic, conjunto – puro, puro conjunto – is a bajo sexto and an accordion; later a voice and lyrics. As Tejanos became more upwardly mobile, conjunto was considered unsophisticated, unrefined, and rustic in an unflattering way. Orquesta "high tone" music was embraced by those fully invested in the American dream. Believing the moment ripe to redeem that investment, some Mexican-Americans thought it meant forsaking Spanish, changing your name from Flores to Flowers, or leaving Texas for places where there was no specific history of prejudice against Mexicans. Conjunto music didn't go away. It just got shunted to the back of the cultural closet.

When rock & roll came, young Tejano musicians heard the siren call just like other young people of the time. San Antonio's Sunny Ozuna squeezed his way through "that tiny eye of the needle" to be the first Chicano to appear on Dick Clark's American Bandstand. People of a certain age still talk about Ozuna's appearance with the wonder of having seen the shimmery shores of the Promised Land.

True Tejano music appeared in the 1970s, at the same time a critical mass of Tejano students began entering universities. Tejano music was born in response to reaching back to those not quite discarded cultural roots (stuffed in the back of those cultural closets), dusting off the old tunes, and trying them on for size.

By the 1980s into the mid-90s, Tejano music thrived and was heard over the air. The big record labels took notice. Contracts got signed and tours were launched. But like the early conjunto before it, Tejano had a different onda. The accordion was still there, but now there were horns, and synthesizers, drums and light shows, and those huevo-smashing pants. The old timers asked, "Que es eso?" even though the same had been asked of them, back in the day when, coming in contact with the German and Czechs polkistas. They, just like the Tejano young bloods, took up that squeeze box and breathed new songs into it, blending what they heard with what they knew of old corridos and rancheras, and made a new music that didn't belong to the Czechs or the Germans anymore, but was unique and distinct, with its own beating heart.

Qué Es "Puro, Puro"?

It's genuinely outrageous to those obliviously living in the comfort of the status quo as to why Tejanos get worked up over what seem the littlest things. It's always the supposedly inconsequential thing that finally, after years of bearing the weight of silence, splits the lip.

When Jerry Avila, creator and host of the 14-year-old PrimeTime Tejano (ACAC), had to quit his day job as morning host of the Super Tejano Primetime Morning Show on KTXZ 1560AM, he was understandably disappointed. But not surprised. "My wife told me," Avila remembered over migas and coffee last November.

Border Media Partners, which had purchased Austin's last Tejano radio station, was moving the format in a direction Avila and other Tejano fans didn't like. When BMP bought Austin's three other Tejano radio stations in 2004 (KHHL-FM 98.9, KXXS-FM 104.9, and KOKE-AM 1600), Tom Castro, co-founder and president of BMP said there would be "no format changes," according to a Houston Business Journal article dated Sept. 3, 2004. Today, those stations broadcast Mexican oldies and Spanish pop. The former KOKE-AM is now all English talk radio, which carries Air America.

Avila says it wasn't long after he started his tenuous job at 1560 (he didn't sign a contract) that he felt the bad onda blowing in as strongly as a blue northern. While he was hired to bring his PrimeTime Tejano brand and prodigious Tejano music knowledge to 1560, he couldn't help but be annoyed when the station kept insisting he play less Tejano and more and more Mexican regional and Norteño music.

"They don't understand the difference," Avila insists. "People who think they know about our music don't know. They may hire someone like me, they may tell me to my face, 'Yeah, yeah – you can play Tejano music' – but we're not part of the discussion. Once the corporation decides what they want to play, that's it."

What BMP and other "Latin" format stations have decided to play is not Tejano, but Mexican regional and Norteño music and Mexican oldies – like Trio Los Panchos and Vicente Fernández – to appeal to the newly arrived immigrant audience. If Tejano music airs, it's hits from the past, not contemporary Tejano music.

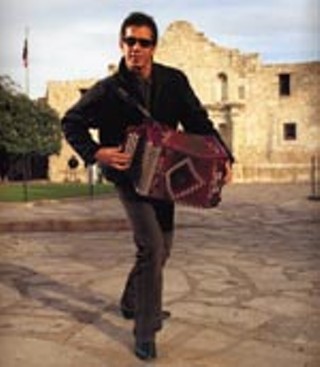

"I have three, Grammy-award winning albums, but you won't hear them played," laments local Tejano musician Joel Guzman. His most recent Grammy came last year for the superb Polkas, Gritos y Acordeónes ("Texas Platters," Music, April 29, 2005), made with David Lee Garza and Sunny Sauceda, respected Tejano musicians, all of them. Guzman makes this point during yet another conversation about the death of Tejano radio: same conversation, same plate of migas, same coffee, same sense of outrage. This time, it's me, Guzman, and later Alberto "Skeeter" Amesquita, who works with El Gato Negro, Ruben Ramos.

My question, "How do you argue with ratings?" is heard as, "You can't argue with ratings." There's a spark of anger when Skeeter asks me in a pointed tone, "Do you listen to Tejano music?"

"No, I don't like Tejano music," I say. "I like conjunto music."

The climate around the table lightens a bit. "Well, you're entitled to your opinion," he says, but does not quite let go of his fire. Why should he?

A Mexican by Any Other Name ...

"It's sad for me to think I can sing you a Mexican song I've heard on the radio, but not a Tejano song," says Elena Quesada Rodriquez (aka, Elena Q), who owns her own media-buying and advertising agency locally. She was a vice-president of programming for the KQ Radio Group for KQQQ 92.1FM and KQQT 106.3FM when it was a Tejano music station. In 2004, when it changed to a Christian music format, Rodriquez walked away.

"I couldn't tell you what Jay Perez's new song is," she shrugs. But she moves beyond crying into the proverbial plate of migas and cuts to the bottom line. The media corporations rely on the Arbitron ratings. The Arbitron ratings say Austin is more than 25% brown, and that many of those brown listeners are newly arrived immigrants. That brings up an interesting predicament.

At the same time mainstream media is gunning for the new brown dollar – changing radio formats, launching Spanish-language newspapers, toying with telenovelas – on a social/political level, the newly arrived are described as the "immigrant problem." Acknowledged and shunned, catered to, yet not quite welcome. For some Tejanos, being anti-immigrant is something they don't want to be when they or their family shares that experience from the not-too-distant past. At the same time, when radio stations are catering to the newly arrived at the expense of existing culture, it's difficult not to flinch. It may seem like a small thing, but the elimination of the Tejano format is that split lip for Tejano musicians and their fan base. What to do about it? The way Rodriquez sees it, Arbitron numbers have to be made more discrete.

"The numbers are skewed," she states flatly. "Arbitron has this process where they ask about the number of Hispanic adults in the household. But Arbitron has no way of knowing if 'Hernandez' is newly arrived or Tejano." More importantly, from the Tejano music fan's perspective, "Tejanos are bilingual. There's a lot of [radio] button punching going on because Tejanos listen to all kinds of music, all over the dial. Whereas a Mexican national or a new arrival will listen to one station. Tejanos have a broader range of educational levels and income levels. Corporate radio brainwashes advertisers into believing that all Hispanics prefer Spanish-only media, and that's just not the case."

That the passions about the lack of Tejano music run high is not surprising given the historical context. But being upset is not going to solve the problem. That's why people like Guzman and Avila and Tejano music supporters are trying to find a new way to deal with an old problem.

"For several years now our music has been slowly taken off the air," starts an e-mail message forwarded to me in early February. "The Tejano music lovers in the State of Texas are being denied the music they grew up with and love from being played on the airwaves in Texas. The big Spanish broadcasting companies think ... that Tejano music lovers can care less if their music was on the air or not. ... Well now's your chance to show your support. On March 12, 2006, one of the biggest rallies in Tejano history will take place at the capital of Texas! Join us for the 'We're Tejanos 2006 Rally.'" The message was signed, "Tu Amigo Pete, Spanish P.D., KRXT 98.5."

"We have to create an awareness all over again," says Guzman. "Okay, we got our asses kicked, but we're Tejanos and we've been through this before. What's happened has forced everyone to connect and hold hands and figure it out."

Rodriquez might have part of the answer.

"When a radio station gets its license, they're supposed to serve the community they cover. Right now, I would say that the Tejano community in Austin is not being served," she says, pointing to the localism issue that appears in other markets across the nation when large, corporate broadcasters move in to communities but forget part of their mandate.

"To me, it's like Univision is the Hispanic version of Clear Channel," Guzman says. "They look for a standard format they can sell in and out of Texas. But the corporate heads, the people making decisions, they have no idea what it's like here. It's like President Bush – he never goes to where the bombs are falling, so he has no idea what is happening."

Outlaw Music

Austin filmmaker Héctor Galán has made documenting Tejano music an important cornerstone of his career with what could be called his Tejano music cycle: Songs of the Homeland, Accordion Dreams, I Love My Freedom, I Love My Texas, and his newest film following the rise of Austin Music Award-winning "Texican" musicians, Los Lonely Boys, Cottonfields and Crossroads, which premieres at this year's SXSW. Through his keenly observed films, Galán pays homage to the music and its masters as he charts the historical underpinnings that thrust it into existence. Yet even he, someone who's fully aware of the changes history brings, is not content to accept what's happening.

"I'm Tejano and I'm still here. So why does anyone think Tejano music is dead?" Galán asks, half jokingly. "Really, we're at a crossroads now. It's almost like a mirror is being held up to the past. But the music is not going to die just because some record executive says so."

Galán and Guzman agree that claiming to be a Tejano musician in the current climate is a brave thing.

"It's like we're becoming the outlaws in the music industry," Guzman says. "Like what happened in country music when Willie Nelson was repackaged as 'outlaw,' in some ways, I think that's happening to us."

So what will become of the music if it's not getting airplay? It will go back to being heard at bailes, quinceañeras, and weddings. The great epoch of Tejano music may have flashed, but no one believes it's dead, just dormant. For now.

The Day the Music Died

Abraham Quintanilla: "No female has ever made it and now you're number one. You cracked the Tejano market wide open. You walked into Mexico and they don't even accept Mexican-Americans and they love you, and now?"

Selena Quintanilla: "And now ... gringos. Disney World!"

Abraham Quintanilla: "And all the barriers that have stopped people before ... you went through them like they didn't exist. Maybe for you they don't exist."

– Scene from the biopic Selena, 1997

Tejana superstar Selena is another lodestone in Tejano music history. Did Tejano music die with Selena? That thought came up over several plates of migas and coffee.

"We were proud of her because we raised her," Guzman says, speaking of the larger family of Tejano musicians. Most Tejano music lovers were pleased to see Selena making her mark not just on Tejano music, but coming close – so very close – to crossing over into the mainstream, meaning, perhaps, that Tejano music would finally take its place among other American musics on a larger scale.

The symbolism of Selena's death and the current condition of Tejano music escapes no one's notice, causing some to ruefully suggest that, "We remained in mourning so long, Norteño music came in without us even noticing." In less guarded language the verdict is, "Los aliens took over."

In the end, the unrealized potential for Selena as an artist and for Tejano music in general still stings. This is ironic, given that Selena's style prior to her death was heavily influenced by cumbia and pop with shades of R&R. Would a Tejano music "purist" criticize her for ruining the form or enhancing it?

"I don't think Tejano music is dead," says Rey Arteaga who plays locally with Son y no Son. "I just think it needs a better marketing stategy. I think it will come back one way or another. Maybe 10 or 20 years down the line, kids will 'rediscover' it."

Maybe a Ry Cooder, who brought back Cuba's musical legacy with the Buena Vista Social Club, and now directs attention to L.A.'s Chavez Ravine. Or maybe another T-Bone Burnett, who brought the music of Ralph Stanley and other old-school roots music to renewed prominence in the Coen brothers' film, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, will happen upon some dusty discs somewhere, in a thrift store, on an old jukebox, or in their parents attics; play them, and get blown away. They'll tell their friends, who will tell their friends. It will become the new old thing, a new outlaw music.

Or maybe the future is closer than we think.

Riding the Cap Metro bus, you hear a lot of things. Sometimes, if you're on the right bus at the right time, you will hear a live performance. One rainy night on the 331, I heard a street-worn man conjure some sho' nuff blues from the hollow chest of his beat-up guitar. At rush hour, on the crowded 1, two young men rapped, commenting on each other's "spit." One of them hated the woman who gave his words away to Goodwill with the rest of his stuff when she kicked him to the curb. That was bad enough until she tried to sell his work to another rapper.

"I mean, that's my spit. How someone else going to give it the same," he makes a fist. "He can say the words, but I know them."

Nothing surprises me on the Cap Metro, but I was caught delightfully off guard one afternoon, when I was riding the 27 and three black teenage girls were singing Selena songs in the back of the bus. "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom" got them working a call-and-response, cracking themselves up. Hearing them sing "Missing My Baby" didn't seem such a stretch, but when they launched into "Amor Prohibido" in fully articulated Spanish – occasionally stopping to correct each other and pause to ponder the meaning of certain words – I was absolutely dumbstruck. They sang "Amor Prohibido" loud and throaty, heads flung back, pulling from that place where body, mind, and soul meet in exuberant harmony.

It was then I had faith that all was not lost. ![]()

All photos, except where noted, from John Dyer's Cojunto, published 2005 by UT Press (www.utexaspress.com). See also www.dyerphotography.com.

And Then There Were None

Can it be true that there were once 10 Tejano music stations on Austin's airwaves? Here's a list of what were once Tejano format stations and what they are now. This does not include some stations like KXTN-FM 107.5, which is based in San Antonio, but apparently can be picked up in certain parts of Austin. – B.A.

KKLB-FM 92.5, "La Lupe" simulcast with KTXZ-AM 1560

(Spanish oldies)

KHHL-FM 98.9, "Exitos 98.9"

(Mexican regional)

KXXS-FM 104.9, "El Gato"

(Spanish contemporary)

KQJZ-FM 92.1 simulcast with KQQT-FM 106.3

(Christian adult contemporary)

KINV-FM 107.7, "La Invasora"

(Mexican regional)

KELG-AM 1440

(Spanish news and talk)

KFON-AM 1490 "Puro Norteño"

(Mexican regional)

KOKE-AM 1600

(Air America)