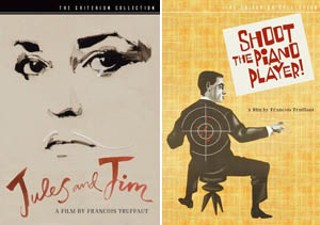

Two From Truffaut

Criterion's 'Shoot the Piano Player' and 'Jules and Jim'

Reviewed by Josh Rosenblatt, Fri., Dec. 9, 2005

Shoot the Piano Player

Criterion, $39.95

Jules and Jim

Criterion, $39.95

Two of the French New Wave's most enduring classics, courtesy of writer/director François Truffaut, come to DVD this holiday season, both in fine, remastered form. Released in 1960, Shoot the Piano Player travels on the diminutive shoulders of its star, Charles Aznavour, who revels in all his deadpan glory as Charlie, a once-famous concert pianist reduced to the status of saloon musician by cruel circumstance and self-sabotage. To watch Charlie's face as he accompanies the manic Boby Lapointe in a frivolous, upbeat dance number is to trace the whole sad history of human resignation: While his fingers dance, the pianist dies. The appearance of Charlie's criminal brother at the beginning of the film forces Charlie out of himself and into the unnerving world of action, where guns, knives, hoodlums, and all manner of classic movie tropes abound. To no small degree, Shoot the Piano Player is about Truffaut's love for American cinema, a transparent and enthusiastic tribute to the art of making movies cleverly disguised as a movie. Aznavour underplays it all perfectly, his almost lifeless performance the life of the film. And as his fleeting, doomed love interest Léna, Marie Dubois is beautiful and elegant and blithe as only an ingenue in a New Wave film could be. Jeanne Moreau was, of course, the ingenue's ingenue, embodying all the New Wave movement's sadness and romance, and her performance in 1962's Jules and Jim is as iconic as they come. Jules and Jim made Truffaut's name and his legend and in some ways defined an era, but it hasn't aged as well as Piano Player. Its story of a love triangle between the two bohemians of the title and the bon vivant but tragic Catherine (Moreau), played against the background of the first half of the 20th century, begins carefree and sentimental but drags through its darkening and repetitive third act. Truffaut just never seems quite as comfortable with tragedy as he does with romance. Moreau, though, is brilliant (both sans and avec moustache), playing a tragically discontented woman who pines for affection and then recoils from its suffocating grasp, leaving the men who love her lost and found at the same time. With these two movies, Truffaut captures all the vitality and cinephilia of the New Wave he helped create in the 1950s. His jump-cuts, freeze frames, and discontinuities are the unhidden scaffolding of his master building and the revealed secrets of his art. Truffaut the personality shines on the DVDs' plentiful and fascinating extras. There's a wealth of interviews on the supplementary discs, both with the director himself and with several of his co-conspirators, including Aznavour and Dubois, who are as eloquent and insightful as critic Pauline Kael in her review of Jules and Jim. Being a film critic first and a film director second prepared Truffaut for the television promotional circuit (especially in mid-20th-century France, where the bar for celebrity interviews was, apparently, set a little higher than the puff-piece self-congratulation we've become accustomed to), and it's difficult not to be taken in by his obvious affection for these movies and by his eloquent intellectual and aesthetic defenses of them.