A Dose of Integrity for Texas Criminal Justice

The Court of Criminal Appeals has created an Integrity Unit – but can the CCA really be part of the solution when it's so much a part of the problem?

By Jordan Smith, Fri., June 27, 2008

In late April, during a Capitol press conference in advance of a daylong meeting of stakeholders – cops, judges, lawmakers, professors of law, and exonerees – for a forum on wrongful convictions, event organizer Sen. Rodney Ellis, D-Houston, told reporters that the state had reached its "tipping point" and that something needed to be done to generate "concrete" and "commonsense remedies" to fix the state's much-maligned criminal justice system. Indeed, the parade of wrongfully convicted continues to march out of Texas' prisons: Thirty inmates have been exonerated by DNA since 2000, 17 of whom were prosecuted by the Dallas Co. District Attorney's Office, which now leads the nation in the number of men exonerated by DNA evidence. Ellis' "real hope," he told the assembled reporters, was that individuals in positions of "statewide responsibility" would now finally step up to the plate to help push for meaningful criminal justice reform.

Just over a month later, Ellis' call was answered – by a most unlikely source. On June 4, Court of Criminal Appeals Judge Barbara Hervey announced that she was spearheading the creation of a so-called Integrity Unit to begin to address the problems with Texas' crippled justice system. According to Hervey's official press release, she is kick-starting the unit "on behalf" of the entire CCA as a "call to action to address the growing concerns" with the system. "Although we applaud all previous studies and dialogue" regarding criminal justice problems, reads the release, "it is now time to act and move for reform." As such, Hervey said that the newly created unit would be seeking solutions to myriad problems: improving the quality of lawyers provided to indigent defendants, implementing procedures to improve eyewitness identification (an insidious problem implicated in a number of exonerations) and to eliminate improper police interrogations (to reduce false confessions), reforming standards for evidence collection and storage, and "implementing writ training," among other areas of concern.

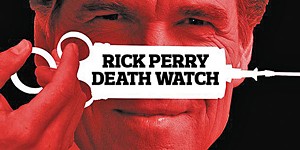

Hervey also announced that she'd chosen a (rather tame) group of 12 individuals to begin the conversation – including Ellis, Dallas District Attorney Craig Watkins, El Paso D.A. Jaime Esparza, defense attorney Gary Udashen, Gov. Perry's Deputy General Counsel Mary Anne Wiley, and UT Law's Criminal Defense Clinic Director Bill Allison. The group will "focus on the strengths and the weaknesses" within the system, reads the press release, and is "not a forum for any particular group" or "one particular political party."

Hervey's "call to action" generated a slew of press – the overwhelming majority of it suggesting that the CCA and, in particular, Hervey are trailblazing crusaders – and every major daily in the state has praised the move on its opinion pages. The crew at the Statesman wrote, "We applaud the [CCA] for taking a big step to bring back fairness to the justice system." Still, it isn't entirely clear how the new unit will function or what, exactly, Hervey – and the court – intend to accomplish.

Indeed, the CCA has consistently been a key part of the problem with Texas' criminal justice system, through years of embarrassing decisions – like in the Roy Criner case, for example, where presiding Judge Sharon Keller opined that DNA found that would exonerate Criner was, essentially, meaningless, because he could've worn a condom when he raped his victim (Criner was eventually vindicated in federal court), or the case of Calvin Burdine, where the court, again led by Keller, opined that a sleeping lawyer wasn't necessarily a bad lawyer. Or, most recently, in September, when Keller arbitrarily closed the courthouse doors at 5pm, refusing to hear the final appeal of Michael Richard, who was then executed even though he likely would've gotten a reprieve had Keller and clan stuck around a few minutes longer.

In short, the court doesn't exactly have the best reputation and, to be fair, hasn't exactly worked overtime to earn one.

And that has led some criminal justice stakeholders to view Hervey's new crusade with skepticism. Some suggest that it is nothing more than a chance to inoculate the court from heavy and continuing criticisms – especially as the number of exonerated inmates continues to grow. Indeed, several court denizens note that the court has had plenty opportunity to correct the system by way of judicial rulings in individual cases. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court long ago acknowledged problems with eyewitness ID, yet the CCA has consistently denied relief to inmates seeking to raise such issues. The topics Hervey has selected are broad and incomplete, some charge – such as with the mandate to "implement writ training." Teaching lawyers to write better writs is fine, but improving the law covering the use of post-conviction writs – to allow better access to the courts for inmates with claims of actual innocence but without DNA evidence on their side – might be a more gritty and useful topic to explore. In sum, says one lawyer, "This is pure PR, and that's not lost on anybody."

Hervey dismisses the criticisms. "Various members of the court have been involved in various 'innocence' ideas for years," she says – Keller heads up the Task Force on Indigent Defense, for example, and Hervey handles the grant funding for training lawyers and judges, she notes. The court isn't seeking to wade into legislative territory with the new unit, she says, though she does hope that the group can come up with some solid recommendations to provide lawmakers in advance of the January session. And she hopes the group will be able to fix some issues with education – like, perhaps, the implementation of better eyewitness ID techniques, she says, "depending on the cooperation of law enforcement." While Hervey admits the topics aren't all-inclusive, she intends for the group to further open up the areas of discussion as they progress through their work – she says that she's heard much grumbling about the need for "writ reform," for example, but isn't sure exactly what that means. In fact, she says she's already made an "assignment" to one group member, asking that the person (unnamed) find out exactly what lawyers are "looking for and why." She says, "Don't throw rocks if you don't tell me what the problem is."

Hervey says she hopes the unit will be able to meet once a month, beginning this summer – either later this month or in early July, although, at press time, a start date had not yet been announced.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.