Point Austin: Supremes v. Texas

"Vote for Show, Map for Dough"

By Michael King, Fri., March 10, 2006

One could readily agree with General Cruz's premise, without necessarily following his syllogism to its hypocritical conclusion. The courtroom in question was the highest, the U.S. Supreme Court, where on Mar. 1 Cruz stood as the defender of the State of Texas – in this instance effectively synonymous with the state Republican Party – seconded by the George W. Bush Dept. of Justice, an oxymoron in its own right. Cruz continues to insist, with thus far unblemished judicial success, that the 2003 re-redistricting of Texas only corrected historical injustices instituted by Texas Democrats back in 1991, and that until the 2002 Republican Legislature seized righteous control of the process, Texas voters had been doomed to elect to Congress Democrats whom they would otherwise abhor.

The problem for Cruz, alas, is that "the preferences of Texas voters" in the congressional districts at issue had indeed reflected Republican choices in presidential and most statewide races – but Democratic choices, and stubbornly so, in the congressional contests. So it wasn't that the districts were "slanted Democratic" – indeed, by party preference and voting patterns, they were precisely the opposite – but that they didn't include the right sort of Republicans, those that ask no complicating questions, vote straight GOP tickets, and elect the kind of Congress Members that would make (most importantly) Tom DeLay proud. So for the re-mappers the issue has never been "the preferences of Texas voters," but the preferences of the state and national GOP leadership.

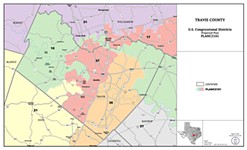

Moreover, Cruz's version of state political history, however reinforced by the now-prevailing state mythology, depends on pretending that nothing happened to the Texas map between 1991 – date of the nefarious "Democratic gerrymander" – and 2003, when DeLay, Tom Craddick, David Dewhurst, and Rick Perry came along to set everything right. Earlier that Supreme Court morning, the Congressional Democrats' lawyer, Gerry Hebert, recounted at some length the intervening history: a failed GOP court challenge; a successful challenge by civil rights organizations; a 1996 re-mapping of 13 of 30 districts on grounds of racial gerrymandering; a 2001 legislative deadlock (engineered by the Republicans) to throw the map to a Republican-dominated federal court; and a re-mapping by that court, weighting 20 of now 32 districts for Republicans. "Yet even under that map," concluded Hebert, "six of those 20 Republican districts still broke Democratic for Congress."

Whatever one thinks of particular episodes in Hebert's history, it is quite a stretch to conclude, with Cruz and the state of Texas, that the 2003 map was intended to "redraw the map to correct the 1991 Democratic gerrymander." Elephants' memories may be long, but they tend to forget disagreeable details.

A Pebble in the Pond

Whatever happens in the case of League of United Latin American Citizens, et al. v. Rick Perry, expected to be decided early this summer, it is likely to be a watershed of Texas and U.S. politics. The fact that the court accepted the case at all – in the wake of its hand-washing on the Pennsylvania redistricting case, Vieth v. Jubelirer – and did so on accelerated basis with the potential to affect this fall's elections, suggests that a majority of the nine justices believes the partisan redistricting issue at least remains open. The 5-4 Vieth decision and its split opinions, including one in which a concurring Anthony Kennedy declared himself still open to arguments on excessively partisan redistricting, could mean that while the court remains split, Kennedy considers the Texas case a troubling one that requires further examination, and perhaps even a new map.

That possibility was certainly in evidence last week, as Kennedy went so far as to describe the radical remapping of South Texas (including Austin-McAllen Rep. Lloyd Doggett's strangulated CD 25), to provide Anglo voters to Republican Henry Bonilla's CD 23 while shoving Webb Co. Latinos into CD 25 as an "affront and an insult" to Latino voters – he told Cruz abruptly that he considers it "a serious Shaw [v. Reno] violation" – meaning it runs afoul of the 14th Amendment by an inappropriate or excessive use of racial categories. Newly minted Chief Justice John Roberts, by contrast, suggested that Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund attorney Nina Perales was asking the court to find a "magic number" that represented either too many or too few Latino voters per district. "What's the magic number?" he kept asking Perales. "What is the number that will make the difference between a constitutional violation and a Latino opportunity district?" As should be apparent to someone even as overeducated as Roberts, if there were a Voting Rights Act Magic Number, there would never be a need to take a racial gerrymandering case to court. Perales kept demurring, but finally responded simply and reasonably, "It depends upon the district."

In that light, at least, Kennedy's questions imply enough votes on the bench – Kennedy, Stephen Breyer, John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, David Souter – to redraw some of the South Texas districts on racial gerrymandering grounds, with reverberations into CD 25 and therefore up to Central Texas. Beyond that, it's anybody's guess, although the Official Order of Court Tea Leaf Watchers (Pundit Division) widely concluded after the hearing that most of the court remains unpersuaded that it can (or should) do anything about "excessively partisan" redistricting. Another four votes – Roberts, Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and (widely presumed) Samuel Alito – seem solid on that question, and the questions of both Kennedy and David Souter in the Texas case suggest that the plaintiffs, mostly speaking for the Democratic Congressional delegation, may have a hard row to hoe on that score.

The Democrats' position – argued at court primarily by D.C. lawyer Paul Smith, and set forth at much greater length in the briefs – is that partisanship is the sole reason for the 2003 Republican redistricting, and that absent some other compelling governmental interest or public good, partisan gain is insufficient to constitutionally justify a mid-decade redistricting, and effectively violates the First and 14th Amendment rights of Texas voters. Some of the justices – most notably Scalia – were loudly unpersuaded that the court has any business getting involved in redistricting, constitutionally a legislative prerogative, at all. Others – notably Souter, Kennedy, and maybe Breyer – more quietly complained that once damp, thence drowned: That is, should the court begin rewriting legislative maps at will, there could well be no end to it. "I don't see the limits of your principle," complained Kennedy to Smith.

Unacknowledged Subject

Bluntly, the odds are better than even that the court – Republican dominated, after all, and now a third or better with the right sort of Republicans – will once again balk at de-partisanizing the Texas map, with the result that the Texas model may well begin to reverberate throughout the country, in both red and blue states. What's to prevent a Democratic legislature elsewhere from redrawing its map to retaliate for Texas, and another GOP state responding in kind ... and so on? The simple answer would be, nothing – and indeed, the court has to be aware that upholding the Texas map and the Texas process is to invite many, many more like it.

That's disturbing enough, although probably an unearned economic boon to political consultants and capital pundits. But equally disturbing in the two-hour, frenetic back-and-forth that is a Supreme Court "oral argument" – polite as they generally are (Scalia always excepted), "argument" is indeed what they mean – is what was left, for the most part, unsaid. For example, only in passing did the discussion touch on the central consequence of "mid-decade" redistricting – argued precisely in the briefs submitted for Austin and Travis County – in that it uses obsolete census numbers to create congressional districts based upon "one person, one vote," although since 2000 a million or more people have migrated into the state and others have shifted radically. The districts are greatly imbalanced, and given license to redo maps every two years, legislatures can rewrite the constitutional numbers at will. "If there's no prohibition," said Waco Rep. Jim Dunnam that evening of his legislative colleagues, "if they think they can do it, they will."

And more troubling in the long run, is that although the Texas case has been argued, inevitably, in largely partisan terms, at bottom the folks most at risk politically are minority Texans, Latinos and African-Americans. Indeed, to the extent the justices accept the Democrats' argument that this was "solely" a partisan gerrymander, that undermines the case of the minority plaintiffs that the effects are felt disproportionately along racial lines. Perales called the South Texas lines "gratuitously and cynically" racial in intent and result, and LULAC's Luis Vera said later, "We've spent 25 years fighting the Democrats, and now we're fighting the Republicans, but we're still protecting Latino voters. That's what this is about."

A week later, the Texas NAACP's Gary Bledsoe summarized some of these underlying problems, and noted again that the interests of the Democratic Party and those of minority voters are occasionally related, but they're not the same thing. He pointed to the dismantling of CD 24, Rep. Martin Frost's former district (anchored in Fort Worth's black community), and noted that among the court's exhibits is an internal state Republican memo warning them not to touch that district because it's a "minority opportunity" district defined and protected by the Voting Rights Act. "Their own expert told them that, and yet they went ahead and did it anyway," said Bledsoe. "If the court allows that to stand, it means a wholesale rewriting of the Voting Rights Act."

Indeed, after Solicitor Cruz finished his largely friendly colloquy with the court, including Chief Justice Roberts (subject last July of a fawning Cruz profile in the National Review Online titled, appropriately enough, "The Right Stuff"), he was followed by Dept. of Justice deputy solicitor general Gregory Garre. Garre didn't get much time, but his argument, made in reference to the same CD 24, was that if a given group of minority voters do not constitute an actual majority of the voters in a particular district, they are entitled to no legal protection under the VRA. "In two Texas districts represented by African-Americans [CDs 30 and 18, represented by Eddie Bernice Johnson and Sheila Jackson Lee], African-Americans are not a majority," Bledsoe noted. "Does that mean those districts are no longer protected by the Voting Rights Act? That's just one implication of this case. If they're allowed to do this, they can completely undermine minority voting rights, all under the guise of 'partisan redistricting.'"

Bledsoe went on to argue that the effects won't stop at Congress, where minority voters are continually in the business of "counting up to 218" to find enough Democratic and Republican members willing to act to protect minority interests, an increasingly dismal project. "If there's a political shift on Commissioners' Court, the same thing will happen in redistricting – and suddenly you'll have no minority seats on the court of a majority-minority county," Bledsoe said. "The implications are enormous for that kind of thing, all through the political process. And it will have a racially polarizing effect – one party will be identified and excluded as the party of minorities, and the other will become the party of Anglos. That's one of the most horrible aspects of this case."

Indeed, among the many lessons one could ponder beneath the awe-inspiring architecture of the Supreme Court in this African-American city ruled by white men, while the learned men (and one nodding woman) debated the finer points of redistricting history, partisan politics, and the constitutional consequences of same – are the extraordinary, institutional, and largely unacknowledged lengths to which white folks will go to maintain political power over people of color, lo these many years. The Texas redistricting case may seem like just another argument over lines on a map, but anybody who's lived here more than 10 minutes should know that the problem of the 21st Century, as of the 20th, remains the color line. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.