Naked City

Measuring accountability

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., Aug. 19, 2005

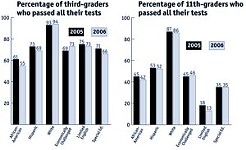

As the name suggests, AYP measures progress. The system, mandated by the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, requires every year a greater number of students from every subgroup (such as Hispanic or limited English-proficient) to pass standardized TAKS tests. This year, 53% of students in each subgroup must pass their reading tests to meet AYP; last year the number was 47%. Schools had to make a 9-point improvement in math, from 33% to 42%. AYP also sets target participation rates (to keep schools from subtly encouraging struggling learners to stay home on test days), graduation rates, and attendance rates.

Continuous improvement is a worthy goal, especially when target rates still have a majority of students failing their math tests. But it also means that improving schools can still miss AYP. Reagan High, for example, showed great improvement last year, including a 16-point jump in reading scores and 18-point jump in math scores for African-American students. Yet the school missed AYP – not because Reagan students didn't improve, but because Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students didn't improve quite enough. "The gains are paired," said AISD accountability director Julie Lyons. A school "could have large gains in performance, but if the graduation rate didn't improve, you won't get credit for those gains."

Even as requirements are increasing, the resources to meet them are not. The four years of NCLB requirements have corresponded to four years of flat revenue for AISD, which can't raise taxes and must give any increased property tax revenue to the state for redistribution to poorer schools.

Of course, money doesn't exactly translate into student performance – in Monday's Board of Trustees meeting to discuss the $755 million budget scheduled for a vote on Aug. 29, Trustee Robert Schneider expressed concern that increased investment in struggling schools did not seem to be paying off in increased improvements. (In response, AISD Chief Academic Officer Darlene Westbrook reminded him that missing AYP doesn't necessarily mean schools aren't improving.)

AISD's TAKS-improvement plans include some items that don't directly cost money, such as longer class periods, or requiring teachers to more frequently test and closely monitor struggling students. On the other hand, such "free" measures do come with a cost when that increased workload translates into increased teacher turnover. Some of the plan's initiatives do have direct costs, such as instructional coaches, curriculum, and other interventions that are getting a couple million new dollars in the budget, even as teachers go without even a cost-of-living pay raise. (To its credit, the district is putting $6 million into teacher health insurance and professional development.)

The choice of where to put scarce resources is a tough one – NCLB isn't called high-stakes testing for nothing. AISD must pay for transportation for any student wishing to transfer from a school that misses AYP for two years in a row. (Students at six schools are eligible, though only about 125 students currently take advantage of it.) The five AISD schools that have missed AYP in the same subject area for three years must also provide special tutoring to low-income students. As NCLB goes into its fourth and fifth years, the consequences will grow more dramatic, such as firing the staff deemed to be responsible for the students' poor performance, or hiring outside consultants to help reorganize schools.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.