Talking Trash

Is the stench of the northeast landfills a WHIFF of things to come?

By Lauri Apple, Fri., May 17, 2002

It's a mild, gray Saturday afternoon in March, and so far today, Trek English hasn't smelled the familiar rotten egg odor that often fills her comfortable Walnut Place home. Neither has her neighbor, Joyce Thoresen, or Harris Branch resident Joyce Best. The three women live near mountains of municipal waste deposited in three adjacent landfills, located between U.S. 290 East and Blue Goose and Giles roads. Sitting around English's dining room table, the three women share odor anecdotes from the past year. Thoresen has lived in the neighborhood since 1969 and says that until last fall, annoying odors wafted from the landfills "only once or twice a year." By last Christmas, however, the persistent stench in the front yard made Best's pregnant daughter-in-law so nauseous, she put her coat over her face and ran to her car.

"The smells are worst on very cold days, or when cold fronts come in," adds English. A Walnut Place resident for 20 years, she founded the Northeast Action Group (N.A.G.) two years ago, primarily to advocate neighborhood development other than landfill expansion and new hauling companies. As N.A.G. president, English represents a coalition of concerned citizens from Walnut Place, Harris Branch, LBJ, Chimney Hills and Chimney Hills North, Austex Acres, and the 18-neighborhood North Growth Corridor Alliance. She has been leading the fight against the landfill companies for the past decade. "For years I tried to trust them," she said bitterly, "but I eventually became convinced they would never do the right thing, because it's not in their best interest."

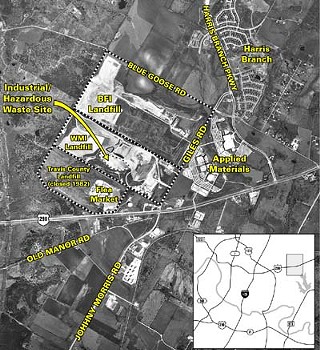

The companies are the world's largest solid waste corporations: Waste Management Inc., owner of the 290-acre Austin Community Landfill, and Allied Wastes/ Browning-Ferris Industries (BFI for short), owner of 352-acre Sunset Farms. About one-third of Austin's municipal waste goes to BFI, and the city also maintains two smaller contracts with WMI. (Nearly two-thirds of Austin's municipal waste ends up not at these landfills but in far southeast Travis County, at locally owned Texas Disposal Systems' site in Creedmoor.) Both landfills are located over the Walnut Creek watershed, just outside the city limits in Austin's extra-territorial jurisdiction, and are under state and county regulatory authority. Because much of the waste originates outside of Austin but lands here, under Travis County jurisdiction, the landfill controversy has both a legal and symbolic boundary line.

The stench, at times overwhelming, is neither the only problem angering neighbors, English said, nor necessarily the most important. She hands over a booklet of photos taken near Blue Goose Road. Until very recently, she says, BFI's "working face" -- where new trash gets dumped and compacted by huge machines -- attracted thousands of buzzards, grackles, and other birds. When the birds weren't hovering around the trash, they'd hang out by a nearby elementary school, or swarm across the street. With so many trash-hauling trucks driving by, she feared the thick flocks would one day cause an accident. "All our roads were nice," she says. "Now it stinks so bad, nobody walks there."

But at the top of the list of landfill-related worries is an invisible one: the legendary industrial waste unit buried under 10 acres in the center of WMI's landfill. In 1972, the state Water Quality Board ordered the site closed, but it still contains at least 21,000, 55-gallon barrels of mostly unidentified acids, solvents, and other chemical materials, in a plot lined only with dense clay. And legally at least, WMI retains the right to use the tract to expand its surface landfill.

In the past few months, in the wake of neighborhood outrage and with new Travis County regulations under consideration, both WMI and BFI have spent tens of thousands of dollars and hundreds of manpower hours to reduce or eliminate the smells, the birds, and other problems. Both sites also have acquired new management, who insist they will urgently tackle any additional problems.

Last fall, Travis County Commissioners discussed the first draft of a proposed solid waste siting ordinance, intended to supplement rules enforced by the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission that address engineering and technical issues. Sponsored by County Judge Sam Biscoe and Pct. 1 Commissioner Ron Davis, the ordinance would regulate expansion of existing solid waste facilities and the siting of new ones. The ordinance classifies facilities by size and category (sludge and composting facilities, recycling stations, transfer stations, and landfills), provides guidelines for setbacks, and is intended to address a complex problem: how to balance the county's growing population and creation of new residential areas with future waste disposal needs. Indeed, the northeast landfills predate many of the houses that sprung up near them in the past decade. While the necessity of landfills is apparent, "No one in Austin," says Davis, "should have to be subjected to intrusions into their quality of life."

Meanwhile, in the next few months, both landfills hope to obtain permission to expand. Sunset Farms, with a lifespan of less than 10 years, intends to grow mostly vertically. Within the next few weeks, WMI expects to send to the TNRCC a final liner design proposal addressing 74 acres set aside for expansion since 1991, when it got a permit for the land after a bitter fight with nearby residents. The companies contend that the county cannot legally limit expansion within their permits' established boundaries, and that no new ordinance can limit vertical expansion of existing landfills. And both companies believe their proposed expansions, under prior state regulation, should therefore be grandfathered and exempt from the county siting ordinance.

Though N.A.G. considers the proposed ordinance an imperfect solution -- their ultimate preference would be to close the landfills altogether -- they say some additional regulation is better than nothing. Even as the odors were worsening, English points out, the landfills were planning to grow. "One reason to support the ordinance is that the odors are so bad, there's no way we want them to be exempt." But she's worried BFI and WMI will find a way around the ordinance. "Even if they wait until it's passed, they might be able to beat it and get expansion, which we don't want."

The TNRCC's 'Sick Standard'

A recent N.A.G. flier contends that the landfills are no longer compatible with the adjacent land use, cause a disproportionate burden to the public health, safety and welfare, and may be polluting not just air quality but also surface and groundwater. As Exhibit A, they cite the recent stench. "We do not want the presidential corridor on Highway 290 between Austin and Bryan to become known to everyone as the PRESIDENTIAL TRAIL OF SMELLS," says the flier. Last winter, complaints to the TNRCC -- which is authorized to impose fines and other penalties on landfills for violating state regulations -- say that on particularly bad nights the smell reached Cameron Road.

In January, BFI acknowledged that Sunset Farms was causing some of the odor, and they installed deodorizers along their perimeter to disperse a citrus smell. The neighbors weren't impressed. "What normal, rational person would think that it is a good idea to try to cover up the problem rather than identify the source and correct it?" asks Walnut Place resident Angela Michaels. "How could the landfills be in compliance with their permits with the level, scope, and intensity of the various odors being emitted?" The stench did not subside, nor did the complaints, which began accumulating in the e-mail inboxes of officials from the city to the state level. The complainants included not just nearby residents citing sleepless nights and sick children, but neighbors with a little more public muscle: nearby corporation Applied Materials.

The TNRCC began its waste program inspection of BFI in early December 2001 as a routine investigation, but didn't finish until three months later due to the odor complaints. In February, the agency began air inspections at BFI, and air and waste inspections at WMI, yet the smells persisted. Feeling the heat, in early March, state Sen. Gonzalo Barrientos wrote to the landfill operators. "Judging from the steady stream of complaints I continue to receive, these [improvement] efforts have not been successful," Barrientos wrote. "It has been suggested to me that the Site Operating Plans you are required to have in order to be permitted by TNRCC are not specific enough to prevent problems ... or to facilitate timely solutions."

Between March 13 and 20, TNRCC inspectors surveyed the landfills for smells, from 8pm to 8am daily. How diligently is uncertain: Some residents say their attempts to reach the inspectors during the investigation were unsuccessful. To issue odor nuisance violations, the TNRCC uses what might well be called "the sick standard." According to agency protocol, odors must reach "category five": causing nausea, headaches, and a need to leave the area, and offensive enough to prevent working or playing in the yard, eating or sleeping indoors, or entertaining guests. Smells also must be "overpowering and highly objectionable."

Although dozens of people complained that the odors were sickening them inside their homes, interrupting their eating and sleeping, and were indeed "overpowering and highly objectionable," Barry Kalda, Air/Waste Section Manager at the TNRCC's Austin regional office, wrote in a March 27 e-mail that no nuisance odor violations could be issued at that time. "The long-standing TNRCC interpretation of the nuisance regulation is that nuisance must be documented on the aggrieved party's property or a similarly positioned affected receptor," he wrote. Simply detecting an odor beyond the landfill boundaries, Kalda said, does not constitute a violation of TNRCC air quality regulations.

Furthermore, say Austin/Travis County Health Department officials, ambient air quality monitoring conducted by the TNRCC's toxicology and risk assessment section in January and February indicated no long-term, adverse health effects. The city's sustainability officer and the Texas Dept. of Health also reviewed the TNRCC's data and concurred. But after the TNRCC ended its onsite investigation, residents complained that the strong stench returned.

'An Opportunity to Reprioritize'

On April 23, both BFI and WMI received notices of violation from the TNRCC based on a documented odor spurred by an April 4 call from Joyce Thoresen's son, who lives in Walnut Place. "It was very strange," Joyce Thoresen said. "I didn't feel that time was any worse than any others. He was just persistent." The alleged odor violations followed notices of enforcement -- one against BFI, and three against WMI -- issued to the landfills on April 2 for possibly odor-based problems, and will be added to the existing enforcement cases.

The TNRCC, as well as the landfills themselves and the city staff, say heavy rainfalls in August and November of 2001 increased production of leachate (water that has come into contact with garbage) and methane, and because the landfills didn't adequately process the leachate and gases, odors resulted. Excessive leachate can lead to the production of hydrogen sulfide -- which gives off a noxious smell that even at sub-regulatory levels can lead people to experience headaches, nausea, and other symptoms. Another potential odor source: large amounts of exposed garbage on the landfills' working faces. Kalda says both landfills had already installed gas collection systems compliant with TNRCC regulations, but the amount of rain may have caught them off-guard.

"We never could identify whether we were the ultimate source, because there are three landfills," said BFI district manager John Fields. "But I could smell gas when I went out there." The TNRCC's monitoring records showed that both landfills had failed to maintain leachate levels below regulatory standards: In BFI's case, inspectors found 3 feet (1 foot is the limit), and at WMI, over 16 feet. BFI wasn't following its own Leachate and Contaminated Water Plan; Fields says the problem has been corrected. "If you get excessive rain like in November, your ability to get to leachate and pump it out is minimized," he explained.

The TNRCC's evaluation showed that WMI's leachate levels had been over the limit since March 30, 2000. Inspectors also alleged that WMI hadn't been adequately monitoring oxygen and nitrogen concentration levels to prevent fires, a matter that the company is discussing with the TNRCC. WMI representatives assert the company is correcting its oxygen concentration levels, but is not required to monitor nitrogen levels and that its field equipment is not designed to measure it. The TNRCC is supposed to inspect the landfill at least once per year, but Kalda says no investigation took place in 2001 because the agency's regional office was short-staffed. Currently, the agency's regional office in north Austin employs only one municipal solid wastes investigator. "I know neighbors think we're not moving fast enough, but all we've been doing is landfills," said Kalda, brandishing the extra pager he wears to take calls about odors in the northeast.

Both landfills say they have since pumped their leachate down to compliance levels, and have improved their gas collection systems. BFI has reduced its bird-attracting working face, installed odor misters and windblown litter collection panels, and erected a long, high fence to capture litter. Last month, it began using 23 newly installed landfill gas extraction wells costing at least $500,000, said Fields. It has also discussed developing a compliance update system with Travis County and a neighborhood hotline for future problems.

WMI has installed nearly 40 odor neutralizers, begun using 6 inches of soil instead of thin tarp to cover exposed trash, and plunked down its own half-million dollars for gas collection system improvements, which should be completed soon. In total, the landfill has 14 gas monitoring probes around its perimeter to verify that landfill gas does not migrate off-site, 61 gas extraction wells within the site (17 installed since April) that feed into the gas-processing system, 10 groundwater monitoring wells, and ongoing surface water monitoring. At WMI, gas generated from decomposing trash gets funneled from the extraction wells into a central processing unit and is eventually burned off at a flare (Trek English calls it "the Olympic torch") that gives off a misty plume during the day and burns bright orange at night. WMI employees have begun checking leachate collection lids every day for leaks, says new WMI operations manager Steve Jacobs, because sometimes they become loose. He doesn't know how often they were checked before he officially arrived on-site April 1, but states frankly, "I know it wasn't every day."

The companies are now working together to address issues such as mud and litter abatement on nearby roads. "Side-by-side, we have a vested interest in making the neighbors happy," Fields said. Coincidentally, Jacobs spent 22 years at BFI before Allied Wastes acquired the company in 1999, and knows the managers and employees across the fence because they used to work under him. Asked about distinctions between the two companies, he jokes, "Their [company] colors are different."

"What we've requested them to do, they've pretty much done," said the TNRCC's Kalda. BFI has told him that the gas flow going into their electrical generators has increased significantly, a sign that it is now being captured and processed instead of floating into the atmosphere. The number of complaints he receives has dwindled from six to 16 per day, to just a few per week (notwithstanding the alleged nuisance odor violations filed against both landfills, before the gas collection system improvements were complete). The TNRCC is only in the first stage of assessing penalties and fines, but Kalda suggests that the recent stench controversy has given the landfill companies "an opportunity to reprioritize how they do business."

Meanwhile, the city cannot directly regulate the companies, says Solid Wastes Services Acting Public Information Program Manager Jerry Hendrix. "All we can basically offer is to say we want you to be a better neighbor." The actual neighbors suggest Austin could also stop doing business with the landfills -- but the city says that isn't possible. In December, in fact, as the stench was growing, the council approved a 12-month extension of its contract with WMI to haul grit and screenings from the city's wastewater treatment plants. Moreover, to the dismay of the nearby residents, the city supports WMI and BFI's bid for exemptions related to the proposed county ordinance, as well as for all other existing landfills with which the city does business. "By not grandfathering these facilities," Hendrix says, "the county would effectively close all landfills in Travis County. This would greatly increase the cost of garbage disposal for all residents by forcing waste haulers to transfer garbage to other parts of the state."

Secure and Reasonably Priced

On a spring afternoon at Austin Community Landfill, the sky is deep blue, the sun shines brightly, and patches of bluebonnets that dot the trash mounds wave in the breeze. Even the air smells good. The refreshing fragrance emanates from mobile misters that neutralize garbage odors, explains Jacobs, WMI's new operations manager. Whether the new misters or other improvements at the landfills will permanently correct major problems -- and resolve the neighbors' objections -- depends on several factors, including company responsiveness to problems and vigilant monitoring by the TNRCC.

Jacobs admits that the company had at first been slow to react to problems. "It's difficult for me to say because I'm new here," he said. "But some of these things, when you come in like I did, you go, 'We probably should have done that three months ago.'" The rainy weather possibly played a role in delaying corrective work, he said, but the corporate office in Houston has supported actions to address the odors "without any holdups."

Jacobs' candor and emphasis on fixing problems contrasts starkly with the dismissive stance neighbors say other WMI representatives have displayed in the past. "We understand that our neighbors would prefer that the landfill did not exist," WMI Project Development Director Glenn Masterson wrote to County Judge Biscoe in January. A few weeks earlier, neighbors had complained to the Commissioners Court that WMI had already begun work in its 74-acre expansion area without notifying them as part of a prior agreement. Masterson was responding to remarks he said were "not only detrimental to our reputation, but were factually incorrect," and defended WMI's "reasonably priced, secure waste management services" to county homeowners and businesses. "If the landfills in the area are not allowed to fully develop to their potential," Masterson warned, "in the future we will see longer haul distances, which will in turn result in more vehicles on the road, more fuel consumption, additional air contamination and much higher prices for waste disposal."

An accompanying "Austin Community Gardens" [sic] fact sheet addressed what the company called "myths" about Austin Community Landfill, including:

In 1996, when the city began looking for a solid wastes company to sign a 30-year municipal solid wastes contract worth between $50 million and $100 million, WMI claimed that Austin Community Landfill could meet the city's needs. Yet in the same year, WMI's annual report to the TNRCC projected a 22.2-year lifespan for the site. Current usage patterns and recent aerial surveys performed to determine capacity, WMI representatives say, show that the already-developed section of the landfill has just an 12- to 18-month lifespan, and even with the undeveloped acreage, only 11 years total. In its fact sheet, the company says it promised to meet the city's 30-year needs "even if we had to transfer some waste to other landfills" -- presumably contradicting Masterson's dire warnings of "longer haul distances, more fuel consumption ... higher prices" etc. As to the industrial waste site, the company says, "We have determined through a third party engineering firm that there is no evidence that any of the waste has left the site."

10 Acres of Unknown Toxins

The Texas Water Quality Board ordered the original owners of the industrial waste site to shut it down in 1972 -- according to one city of Austin-commissioned study, due to "possible groundwater contamination." Thirty years later, the same fear remains.

Yet subsequent landfill companies continued using the surrounding area through the Seventies. In 1981, WMI took over for the then 216-acre site through a subsidiary, and began storing garbage around the 10 toxic acres. Ten years later, a site investigation of the abandoned county landfill commissioned by Travis County said trash "forms a continuum" between the county landfill and the WMI site. It also affirmed that watercourses on the abandoned county landfill feed into Walnut Creek, which, in turn, flows into the Colorado River. One of those watercourses runs through WMI's landfill, just south of the industrial waste site.

The county's study identified the waterway as "the creek," a term Trek English and other landfill neighbors also use. WMI, on the other hand, deems the creek a "drainage ditch." And the city refers to it as a tributary. "The definition depends on your perspective and political motivations," said Chuck Lesniak of the Watershed Protection and Development Review Department. "Any of those terms is correct. The neighbors call it a creek because they want to raise its significance. WMI, I think, calls it a ditch because in their minds, it lessens its significance." Whatever its rightful name, Lesniak says, when rainfall occurs the tributary/ creek/ditch becomes a stormwater runoff channel that carries water to Walnut Creek -- and therefore, an issue of environmental concern.

In the late 1990s, the city considered offering WMI a major chunk of its 30-year disposal contract, but during the negotiating process, neighbors and local environmental groups asked the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to declare the industrial waste site a Superfund site. If the EPA had bestowed the Superfund designation after the city had begun dumping trash there, the neighbors warned, the city eventually could have been held responsible for some cleanup costs. The city rejected WMI's bid in part due to concerns about the site, and requested an investigation for possible groundwater contamination. (Monitoring of the site is not required by the TNRCC.)

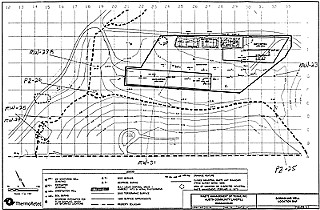

WMI hired ThermoRetec, an environmental consulting firm, to investigate the industrial waste site. A considerable concentration of 1,4 dioxane -- a suspected human carcinogen -- was detected in samples from a monitoring well and a piezometer, which measures groundwater levels. The same piezometer and another monitoring well picked up concentrations of the carcinogen benzene. (All three monitors were concentrated at the site's western perimeter, and were the only ones from which ThermoRetec drew groundwater samples -- even though the original investigation plan called for additional wells, and neighbors had recommended some wells to be placed south of the site, closer to the Walnut Creek tributary.) J.D. Consulting, a firm hired by WMI to do a human health risks assessment, predicated its report on ThermoRetec's findings, but concluded that no risks existed requiring remedial action based on the classification of water in the area.

Trek English and other landfill neighbors called both reports "incomplete and inconsistent." TNRCC municipal solid wastes permit team leader Jeff Davis, who examined the report as part of the agency's "courtesy review," agrees more could have been done, but notes that it was a voluntary investigation. "On the positive side, we now know a lot more about the characteristics of the wastes that were put out there," he said, "and we know that there has been some contaminant migration from the unit." The site's clay soil inhibits water flow and would give the company time to contain a potential burst of one of the 21,000 barrels, he says. "Fortunately, if they have a significant release, it wouldn't change the groundwater velocity, which moves only a few feet per year. If they need to take corrective action, they'll be able to contain it before it's a problem." The TNRCC believes no risk exists at the site; Davis attributes some of N.A.G.'s persistent complaints to "a lot of hard feelings. These folks feel they've been lied to."

In early 2001, English and others compiled a list of 31 discrepancies in the two reports. The firms had cited different measurements of the clay liner beneath the site, they found. When discussing land use, J.D. Consulting did not mention the nearby Harris Branch and Chimney Hills neighborhoods, the day care center, or the elementary school. And ThermoRetec's conclusion that groundwater near the industrial waste site moved only in one direction contradicted an earlier study showing groundwater moved in several directions. Although ThermoRetec found no evidence that toxic materials enter the drainage ditch, neighbors argued that it's impossible to be sure, because no samples were taken from the ditch itself.

The city's review "generally agreed" with the neighborhoods' concerns about the reports, says Lesniak. While city staff believe sufficient data exists to show which way groundwater flows, he says additional monitoring points could have more accurately measured flow rates. A groundwater monitoring plan jointly developed by the city and WMI is expected to provide more accurate and frequent assessments of water flow changes and groundwater level measurements to identify potential concerns, such as leachate reaching levels high enough to threaten the integrity of Walnut Creek. The plan will also include monitoring of neutralized "acid pits" on the site, he said.

In addition to this monitoring, the city's agreement with WMI calls for placing a 5-foot clay cap over the industrial waste site to reduce the formation of leachate and pressure for leachate migration out of the site. According to Lesniak, the agreement requires WMI to hire a third-party contractor to verify that the cap meets specifications outlined in its agreement with the city. Jacobs says the job should be completed by the end of the year. Sounding disappointed, the TNRCC's Davis said, "I thought they had capped that already."

The surface of the industrial site now appears brown, flat, and otherwise unremarkable. WMI's Jacobs says he hopes that once the cap is in place, the site will "fall off the radar screen." But that surely won't happen if WMI ever pursues storing trash above it. WMI says it currently has no plans to expand over the industrial waste site, but hopes that in case it ever wants to, it can. "Even if it's a small crack and there's a giant bear on the other side, we'd like to leave the door open," Jacobs said. "From a technical standpoint, you could do it. But from a PR standpoint, you might not. It would be very expensive, would require geotechnical work and engineering to prove it was a stable platform to build a landfill on.

"Personally, it's probably the last place out here I'd ever want to put garbage," he continues. "But from a company standpoint, it may be such that the economics or changes in the future will mean we need to go into that area."

Cards on the Table

In an attempt to resolve the standoff over the landfills, the county formed a nine-member working group including residents such as Trek English, landfill representatives (including Texas Disposal Systems), and other stakeholders. The group reached consensus on several issues, including aspects of siting, public notification and enforcement, and rules for variances.

But the group strongly disagreed on whether and how the ordinance should apply to the vertical expansion of existing landfills. Therefore, the county has prepared two working drafts. The first, preferred by the companies, allows landfill expansion based on a contract between the county and the landfill operator. The second, favored by the northeast neighborhood representatives, would require existing facilities to abide by stricter siting criteria for new landfills. "Draft B" also contains a more detailed variance provision, "in anticipation that landfill owners will seek that form of relief." Commissioners could vote to approve Draft A or B, or else return to the drawing board for another round of drafting. But for the neighborhoods around the existing landfills, the clock is ticking -- and the landfill companies appear to have an ace in the hole.

Commissioners took public commentary on the ordinance three weeks ago, but Judge Biscoe postponed further discussion until May 28. In the meantime, County Attorney Tom Nuckols credits the landfill companies for voluntarily refraining from filing their expansion permits, which he says has kept the negotiations between them and the neighbors "manageable." But, he adds, even if the court approves the ordinance, the county must post it for 30 days before it can take effect -- that would be July at the earliest. In that interim, WMI and BFI could file their papers with the TNRCC and declare themselves exempt from the pending county ordinance. "I'm not convinced that [rights to claim exemption] would be true," he says, "but that's their trump card. I believe they think it would improve their position."

WMI recently cleared its expansion tract and put in erosion control measures, and has begun excavating dirt from the land. Meanwhile, Attorney Paul Gosselink, counsel for BFI, says the exact dimensions and other particulars of its intended expansion -- details dealt with by the TNRCC -- remain unresolved, but that the company has prepared a "request to enter an agreement" with the county. "We're trying to work within the system."

On a municipal level, in March the City Council-appointed Environmental Board concurred with earlier recommendations made by the Solid Wastes Advisory Commission (also council-appointed) and passed a motion "strongly" urging council and staff to take a leadership role in addressing odor problems. Among other things, Board members also recommended the city to oppose the landfills' expansion until the odors were fully resolved, to explore whether it can issue nuisance violations of its own, and requested an "extensive review" to ensure compliance with the watershed ordinance and Clean Water Act. But city staff says the city has insufficient resources or regulatory authority to monitor the landfills.

Neighbors say the odors haven't completely dissipated. "I will say it's gotten better, but we still smell it" -- especially around Blue Goose," said Chimney Hills resident Bryan Paschall, who sent about five e-mails to Kalda during the stench crisis. "We're all worried about our property values, and our children."

Trek English and other residents have collected more than 1,000 signatures from people across the city asking the county not to grant the landfills vertical expansion rights or exempt them from the new criteria. English will wait and sees what happens with the ordinance -- and cross her fingers that the rotten eggs smell won't return again in full force. She still doesn't buy the landfills' argument that the rain caused the odors -- it has rained on the landfills before, she points out. Something has changed.

"We're dealing with Third World issues," she says, "in the most modern country in the world."

On April 29, the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission's Region 11 office sent Browning-Ferris Industries additional notices of enforcement for four outstanding alleged violations related to erosion control. The office will fold the alleged violations into its existing enforcement case against BFI for excessive leachate. "Overall, the facility operations appeared well organized and considering the nature of the facility, reasonably free of large amounts of loose trash," the inspectors reported. On May 6, the TNRCC sent a notice of enforcement to Waste Management Inc. Inspectors detected two outstanding alleged violations, also related to erosion control.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.