One, Two, Tres, Cuatro: The Sum Is Greater Than the Whole of Its Parts

Thirty-five years later, only who's doing the clutching has changed

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Nov. 25, 2011

[Editor's note: The following was intended as the debut of "One, Two, Tres, Cuatro," but matters of life and death intervened last week.]

The phrase danced around in my life, but one day in the mid 1970s, it appeared as the headline for a story in the Austin Sun. The cover was purple – not the garish purple misstep of the Chronicle's first issue, but a clear lavender surrounding a ragtag group photo of Willie Nelson's family.

John T. Davis wrote the story, something I recall with a latent pang of envy, for we were both around 22 and unofficially in the elementary grade of young writers at the Sun. And there he was getting a cover story, "The Sum Is Greater Than the Whole of Its Parts." Perhaps his being a more accomplished writer had something to do with it, but I was brash enough to imagine I ranked.

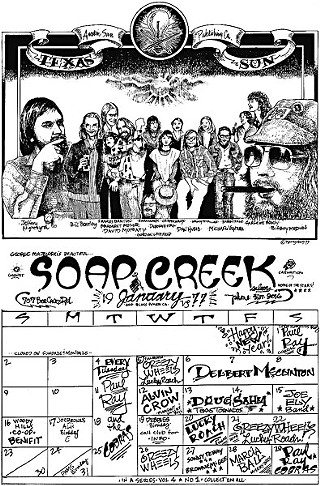

The phrase floated and fermented, took on a different shade there in the warm family of the Sun, which I joined in May 1976. We posed one chilly night at the 16th Street offices for the photo Kerry Awn then drew as the Soap Creek Saloon calendar. I'd set my hair in hot rollers for that tumbly, curled Farrah Fawcett look every woman tried at least once and wore a Uranium Savages T-shirt while holding a puppy named Rhiannon. I'm ready for my close-up, Mr. Awn.

The biweekly publication bore radical chic bloodlines in Editor Jeff Nightbyrd, who'd been deposed by feminists as editor of the militant underground newspaper Rat and who then served as national vice president of Students for a Democratic Society. Around him gathered a storm of young and veteran talents – writerly ones like Michael Ventura, yes, but also photographers like Alan Pogue and artists like Jack Jackson. In the illustration, Nightbyrd strokes his beard, a common stance for him. Nearby is sportswriter-turned-E! TV founder Big Boy Medlin, whom I truly worshipped, and Music editor-turned-record label honcho Bill Bentley, my longtime friend who then regarded me as an upstart usurper.

Managing Editor Dave Moriarty raised his arm in a show of strength; here was a character whose part in the sum I wouldn't fully grok for many years. He scared me then, this Port Arthur refugee with penetrating eyes who helped found Rip Off Press in San Francisco. At the Sun reunion a couple of years back, he grinned at me: "You were a young pup who wanted to play with the old dogs, but thought you had to act the whore like Janis [Joplin]."

It was the truth. With no previous experience or high school diploma, I sought out the Austin Sun, and here we were in the class picture.

Less celebrated were the women of the Sun, intrepid saleswomen like Deb Stall, who actually got businesses to buy ads that made it possible to collect those $15-a-week checks, or Carlene Brady, whose artistic vision shaped the paper in ways never fully acknowledged. And the marvelous presence of Sara Clark, who took the time to explain to me not only what defined sans serif fonts but why fonts mattered and the artistry of their appearance. She also graciously explained to me why the wet jockey shorts contest I proposed was not really the solution to the wet T-shirt contests so popular then. When Sara died some years ago, I felt her loss in innate ways.

That calendar is the perfect freeze-frame for that moment in a discontented, disconnected life. I had no clue what writing about rock & roll would mean, or that almost all the people in the drawing would still be in my life 35 years later. In Kerry Awn's black, inky style, we were the sum, so much greater that the whole of our parts.

During the Sun years, I worked many short-term jobs to support my writing habit. They were often restaurant or mall store jobs, easily gotten and easily discarded. One job I particularly liked was at a medieval-themed restaurant, which piqued my interest in British history and early music. The restaurant hired several dozen twentysomethings to play the parts of servers and performers, roles adopted with such enthusiasm that "Roll Me Over in the Clover" became offstage sport as well as an onstage song.

The staff/cast partied like ... well, like young men and women in their late teens and 20s, wild and free and in the throes of the Bicentennial America of Dazed and Confused. The attractive, hormone-heavy cast – often aspiring performers or actors – wove youthful marriages already falling apart into new relationships, friendships, gender-orientation exploration, and other carefree pursuits. And lots of sex.

I wasn't a performer. I answered the phone and took reservations using a fake English accent, one polished in junior high. For this job, I adopted the mannered tone of Julie Christie in Far From the Madding Crowd effectively enough to land the position and loved its fun and freedom. Even the manager was cute, so I wasn't upset when, one morning as I wrote in the reservation book, he slipped up behind me and pressed his erection against my bottom. He was new on the job, one day. I slept with him that night.

A few days later, the restaurant's owner flew in from England – straight out of London Central Casting with a pasty complexion, tobacco-colored teeth, and a dyed comb-over. The second day he was there, I was dispatched to his hotel room to deliver papers, and he answered the door wearing a bathrobe. Once inside, he – the owner of the company – riffled the papers then asked how much to spank me. I don't remember what I did, probably giggled and ran out.

Was that sexual harassment? Maybe with the manager, though I was foolish and horny, and he was around my age. Definitely with the owner, who was at least 25 years older than me. Still, it's not the same occupational hazard of having to extract myself from the unsolicited clutch of a subject I'm interviewing. The last time was a legendary blues singer. He took my hand, gazed meaningfully in my eyes, and tickled my palm suggestively.

I just smiled, shook his hand, and thanked him for making great music.