Reefer Madness: A Victory for Proportional Sentencing

The House Judiciary Committee has voted to end the disparity between sentences for crack and powder cocaine

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Aug. 14, 2009

After years of urging by federal judges, especially those on the United States Sentencing Commission, members of the House Judiciary Committee on July 29 voted to finally do away with the 100-to-1 federal sentencing disparity for crack and powder cocaine.

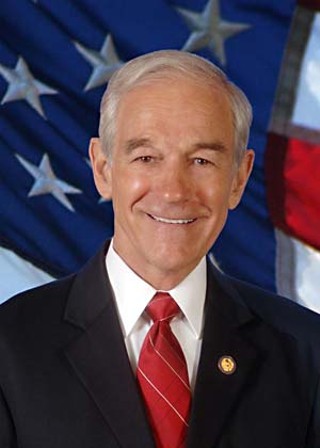

Under the bill that lawmakers passed 16-9 last week (House Resolution 3245, by Virginia Democrat Rep. Bobby Scott, joined by 32 co-sponsors, including Houston Democrat Sheila Jackson Lee and Surfside Liberpublican Ron Paul), separate penalties for possession of crack cocaine would be eliminated altogether, leaving in place only penalties for possession of cocaine. The bill now goes to the whole House for consideration. Significantly, under the proposed adjustment, the five-year mandatory minimum sentence for possession of just 5 grams of crack would completely disappear. Left in its place would be the man-min sentence triggered by possession of 500 grams of any type of cocaine, crack or powder.

The 100-to-1 crack-to-powder disparity was codified in 1986, in the wake of the death of basketball star Len Bias, as lawmakers jumped to do something about the "scourge" of crack that they saw sweeping inner cities. In signing into law the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, President Ronald Reagan said that it was one way "not just to fight" drug use and abuse "but to subdue it and conquer it." The "magnitude" of the problem the U.S. faced, he opined, could be traced to a "past unwillingness" to recognize the problem. The "vaccine" that would end the issue "is a combination of tough laws – like the one we sign today – and a dramatic change in public attitude," he said. "We must be intolerant of drugs not because we want to punish drug users, but because we care about them and want to help them."

Sheesh, if that's what he considered helping ...

The truth is that being intolerant didn't do much to help at all – instead it has filled our prisons with users and has punished not only those individuals but also their families. Moreover, the disparity in crack and powder cocaine sentencing disproportionately impacted minority drug users – especially African-Americans – and their families. In a 2007 report, the U.S. Sentencing Commission said that the crack-cocaine sentencing scheme was simply wrong: It sweeps "too broadly," has disproportionately affected "low level offenders," and overstates the "seriousness of most crack cocaine offenses," failing to provide "adequate proportionality."

For possession of a minor amount of crack, years of freedom would be lost for thousands and thousands of low-level offenders – as would access to education (and to money to pay for education), access to housing, and access to employment. And did crack – or any other drug, for that matter – disappear? No.

Indeed, in arguing against the equalization measure during a meeting of the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, several members, including Tyler Republican Rep. Louie Gohmert, said that the 1986 law was actually meant as a way to help black communities – with support from backers including Rep. Charlie Rangel (who has since come out in opposition to man-mins, period), the "intent was to do great assistance to African-American communities, where crack had taken such a strong hand," Gohmert told the committee. (Amazingly, Rep. Darrell Issa said that the best way to remedy things would be to decrease the man-min sentence-triggering amount for powder cocaine to 5 grams. Crime rates have declined in cities across the country during the last two decades, and Issa apparently believes that decline is thanks to the 1986 crack bill. To do away with the crack law now, he told the committee last week, "would be to surrender after winning the war.")

Regardless of how Gohmert or Issa thinks the change in law may affect drug crime, the reality is that the Fairness in Cocaine Sentencing Act of 2009 seeks only to atone for more than two decades of disparate treatment at the hand of the federal government in but one small area of the endless war on drugs. Indeed, the majority of drug crimes are prosecuted and punished at the state level, and there is little worry that officials in most states – and certainly not in Gohmert's Texas district – will be willing to surrender the war there.

But there's always hope for tomorrow.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.