How the Red River Cultural District Was Made

Decades of off-kilter activity and music activism culminate in our current concert hub

By Rachel Rascoe, Fri., Jan. 31, 2020

Standing on the top deck at Mohawk feels like floating above the world. From the top risers, a bird's eye of bands and fans buzzing below gives way to a sweeping view of our city's last concentrated music corridor. It's a panorama of Red River, with a vantage on each and every compartment.

Show-hoppers hike up the sidewalk outside, and the big tour buses line up in front of Stubb's. Beyond Cheer Up Charlies' pink glow, there's a smaller neon insignia at the corner of Red River and Ninth. The Red River Cultural District sign, a late addition compared to the rest, goes largely unnoticed in the action.

Still, the display presents a focal point for the current era of Austin music activism. The local title earns name-drops in discourse on an industry struggling nationally, like a recent Billboard piece titled "Indie Concert Venues Stare Down Developers in Face of Rising Rents, Gentrification." It's in that pressure cooker of forces that the cultural district formed – and has emerged as ground zero in the contemporary fight for local music.

What's In a Name?

In 2012, Jennifer Houlihan faced a long table of Austin music industry titans. In a purple suit and heels, she came overdressed to the interview. The esteemed all-male lineup included Stubb's principal Charles Attal, Mohawk owner James Moody, and SXSW CEO Roland Swenson, all of whom helped launch the collaborative nonprofit Austin Music People (AMP) the year prior.

Cosmic Coffee owner Paul Oveisi, then head of Momo's on West Sixth, initially took the helm of the experimental group. His LinkedIn description that year read, "This stuff is hard." Behind Houlihan as its new executive director, AMP zoomed in on the blocks of Red River between Sixth and 12th. Rumors of the city redeveloping Waller Creek akin to San Antonio's River Walk prompted concern over club displacement.

In a final push to convince City Council, AMP held a United We Jam fundraiser at over a dozen citywide venues in August 2013, registering voters and gathering thousands of signatures in favor of the "cultural district" designation. On Oct. 17, 2013, the civic body approved the Red River Cultural District (RRCD). The new lingo made national headlines when Moody proposed a statue of Misfits frontman Glenn Danzig atop a dragon to the Music Commission.

"The biggest thing we got was public recognition that these weren't just fly-by-night, seedy dive bars that you could forget about," says Houlihan today. "Red River is a real part of the economic engine of Austin. It keeps the music industry alive."

AMP recognized the cultural district assignation as a marketing tool to differentiate Red River from Sixth Street. Cody Cowan, current executive director of the RRCD, simplifies it as "a thumbs-up from the city" without any zoning protections from development. The title's ephemeral nature came into quick focus in 2015, when neighboring Seventh Street venues Holy Mountain and Red 7 both faced major rent hikes while struggling to renew leases.

Holy Mountain partner James Taylor, a key player in early RRCD advocacy, suggested the group may have been victims of their own success in rebranding the side street as a live music center.

"The issues that the cultural district has addressed are to make that neighborhood more desirable to everybody," he told the Chronicle in May 2015. "Is it frustrating to think those things could be part of our demise? Yeah, but I don't regret tackling those issues. They're important."

The Soul of Red River

Souly Austin, a new initiative from the city's Economic Development Department, proved the perfect opportunity to give the district name some teeth. The program helps local businesses form merchants associations, and the RRCD proved the first guinea pig to cross the finish line. Souly Project Manager Nicole Klepadlo recalls the initial meeting of district leads at Mohawk.

"That magic moment was seeing all those venue operators shaking hands for the first time," explains Klepadlo. "A lot of them, historically, have been competitive."

"Ryan Garrett at Stubb's and I worked down there for 20 years plus, and we had never shared a full sentence," furthers Cowan. "At Nicole's meeting, we looked at each other like, 'Oh my God, we're like the same person.'"

Officiated as a nonprofit in 2016, the area's new merchants association used Souly seed funding to launch Hot Summer Nights, an amped-up July edition of Free Week. Cowan says the collaborative work to round up sponsors, performance payouts, and food specials bolstered district participation, which now extends to some 40 businesses of all kinds.

In the realm of civic advocacy for music interests, RRCD venues offer a prominent presence. When a series of unrelated gun violence incidents shook the district last August, Cowan and Garrett's tag-team efforts pulled together an emergency district meeting with the mayor, leading to increased police presence. While Souly does not offer ongoing city funding, Klepadlo helped the district secure funding for fencing, sidewalk, and lighting improvements.

Arguably the biggest boost for those concerned sounded a bit mystical at the time. In 2018, Cowan left his job as Mohawk GM to become the RRCD's first executive director, with an anonymously donated salary. He now confirms it's supported by Keller Williams CEO Gary Keller's Austin Music Movement nonprofit umbrella, which also supports Rebecca Reynolds of the Music Venue Alliance Austin and Patrick Buchta of Austin Texas Musicians.

Cowan says he's halfway through a three-year salary donation and is hopeful about identifying ongoing sources of funding for his organizing work. Compensation for full-time advocates presents a vital ingredient, considering rigorous music industry hours limit most venue operators' presence at City Hall. Previously dominant music org AMP eventually dissolved after Houlihan resigned in 2016, citing concerns about sustainable funding for the organization.

Music at the Fringes

Before landing on the cultural district tag, advocates considered labeling it as an entertainment district. Houlihan says the former left more room for dreams of coffee shops and records stores on the strip, while also reflecting Red River's ragtag history through so many different phases of commerce and residents. One flagship is the German-Texan Heritage Society.

Located behind Mohawk in the mid-1800s' German Free School, the structure represents a bygone neighborhood of immigrant settlers from the same era. The street eventually moved through identities as an automotive hub – well-suited as one of the only flat streets running north-south in Austin – and antiques destination. It's easy to imagine the petite cabin interior of Cheer Up Charlies, in a past life, as a car lot office surrounded by vehicles instead of patio furniture.

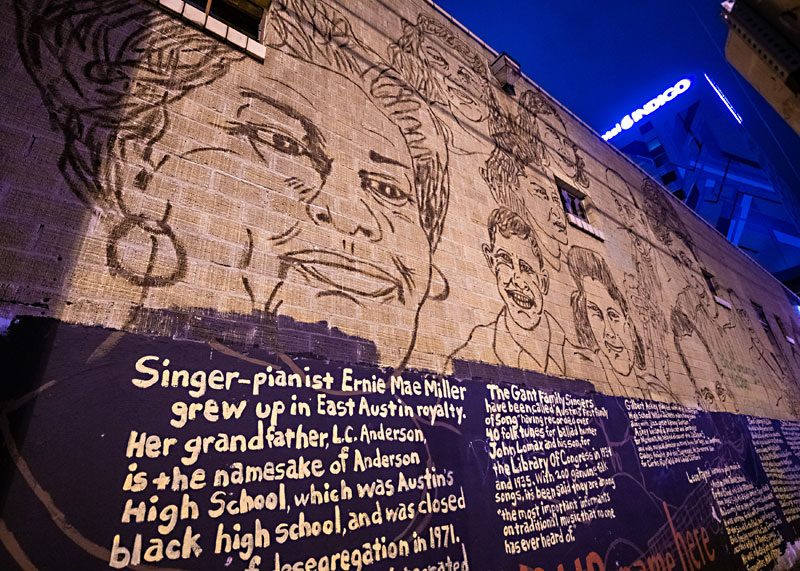

This image appears in a 1,000-word history of the street by local music journalist Michael Corcoran, painted in white by Big Boys/Poison 13 punk legend Tim Kerr on the corrugated metal side of Elysium. Grants from the Souly Austin program supported the new mural in 2017, as well as the district's neon sign. Reborn as a Texas historian after a long stint at the Austin American-Statesman, Corcoran's take makes the street sound like hallowed ground.

"Red River had an edge, but the flow was inclusion," he writes. "During the era of segregation, black-owned businesses were next door to white-owned ones on Red River from Sixth to 15th streets. This was as close to the Eastside, both spiritually and physically, as you could get in Downtown Austin."

Corcoran and Kerr continued on the side of Stubb's with a mural of eight underrecognized figures of Austin music. This time, they matched the former's live-wire blurbs with the latter's keenly imperfect portraits. The collaboration inspired their upcoming book, [Ghost Notes]: Pioneering Spirits of Texas Music, due March 25 on Texas Christian University Press.

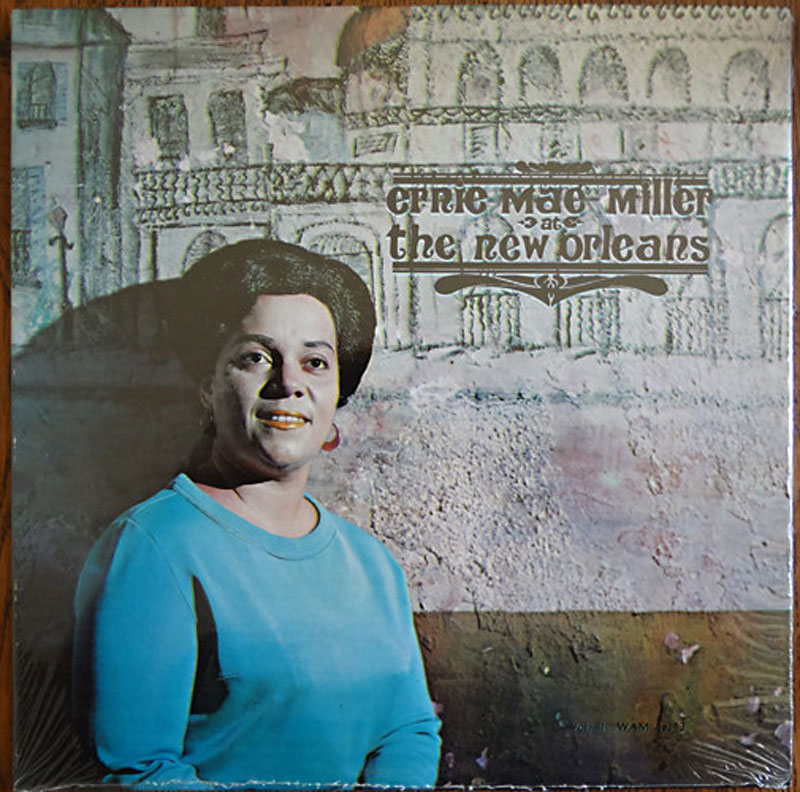

One face on the brick wall, jazz pianist and vocalist Ernie Mae Miller, occupied a 15-year residency in the downstairs Creole Room of Red River's New Orleans Club beginning in 1951. In the Sixties, the 13th Floor Elevators debuted their first single "You're Gonna Miss Me" at the venue, one of Red River's first wider attractions. Janis Joplin sang nearby at the Eleventh Door, now home to the Austin Symphony box office at 11th and Red River.

Amidst widespread building condemnation during the Seventies' Brackenridge Urban Renewal Project, the New Orleans Club was picked up, placed on a flatbed trailer, and driven one block down the street to the new Symphony Square development. In the early 2000s, ghost hunters on a British television show searched for Joplin's spirit in the buildings. They surmised that the late Port Arthur powerhouse may haunt the site of her transformative choice to chase fame in San Francisco over singing with the Elevators.

Today, the Symphony Square complex headquarters Waterloo Greenway, the rebranded Waller Creek Conservancy. Meanwhile, the New Orleans Club rents for private parties with the attached guarantee: "The minute your guests pull open the glass-front double doors ... they'll feel the pulse of Austin's urban past."

Making Advocacy Last

Plenty of off-kilter clubs peppered Red River from the Seventies on, notably the One Knite, Blue Flamingo, Cavity Club, and Chances. Yet it wasn't until Emo's and Stubb's set down roots in the Nineties that a row of consistent locales filled in the intermediate blocks, providing an alternate runway from Sixth Street for SXSW, which began in 1987. In 2001, the mega-festival/conference's sponsoring paper – the Chronicle – declared, "Austin's Former Crack Alley Is the New Place to Be Scene."

As such, Red Eyed Fly owner John Meyer expressed plans to organize the new crop of venues – Beerland, Headhunters, Room 710 – "into a cohesive neighborhood organization similar to the Downtown Austin Alliance." The latter club's Woody Weideman said he wanted to buy his building first, already predicting rent hikes during the early Aughts buzz about Red River.

In the 2013 City Council resolution, the cultural district designation came framed as a platform for later state recognition. Cowan maintains this as a "high priority" and says he hopes to begin the application process this spring. The list of "success factors" for a state cultural hub reads like a checklist of recent RRCD upgrades: clear signage, a website, and special events.

Cindy Widner explored the overlapping puzzle of preservation initiatives in a 2015 Chronicle article on the RRCD ("Protect and Preserve," News, July 24, 2015). While Texas' designation as a "cultural district" facilitates access to grants via the Texas Commission on the Arts, she pointed out that only city of Austin recognition as a "historic district" can protect buildings and adjust zoning. Civic endorsement in that quarter aligns with the long-brewing Agent of Change policy, which makes incoming residential and hotel developments responsible for soundproofing against already-present music venues citywide. Music Commission Chair Rick Carney singled out the issue as a priority for 2020.

"The larger issue is how we can translate a cultural heritage based largely on the scruffy, the off-kilter, the independent, the casual, and the (superficially) unconcerned with mainstream success into a form that keeps it authentic and alive," wrote Widner four years ago.

Today, the RRCD isn't afraid to appear concerned with success. Despite the continued success of anchors such as Barracuda and Empire Control Room, almost half of the district's clubs have closed in the last five years, so every avenue of preservation is on the table, whether acquiring city protection or working with developers. Both Houlihan and Cowan brought up the concept of a music venue on the ground floor of a new high-rise.

"The thing about Red River is that it just kind of happened accidentally over 20 years," adds Cowan. "There was Emo's on one corner, Stubb's happened, and it just started booming.

"Suddenly, things are changing in the opposite direction citywide," he continues. "We're asking who are we, what is our identity, and what do we want this to be? There isn't a template that we can just steal and replicate for music advocacy, because we're all pioneers."

Distinctive Neon Gateway

After the formation of the Red River Cultural District, grants through the Souly Austin program helped spruce up the street with two murals by Tim Kerr and Michael Corcoran, as well as another art piece outside of Cheer Up Charlies by Matthew Briar Bonifacio. Merchants association members also envisioned an RRCD sign, described in a 2017 strategy report as a "distinctive neon gateway." All Souly-supported projects were matched by private support from district businesses, sorted out in partnership with creative consultants Public City. Stubb's GM Ryan Garrett – now Beerland's owner as well – donated space on the corner of the venue's VIP lounge at Ninth & Red River, as well as the majority of financial support. San Marcos' Blackout Signs and Metalworks built the luminous welcome message, matching their earlier handiwork on the Stubb's Bar-B-Q emblem down the block. The RRCD centerpiece finally switched on in summer 2018.