The Overthinking Man's Fighter

Floyd Patterson biographer W.K. Stratton explains the appeal of boxing's gentleman eccentric

By Josh Rosenblatt, Fri., July 6, 2012

In late September 1962, Floyd Patterson, the youngest heavyweight boxing champion in history, boarded a plane for Madrid. Only days before, he'd lost his belt to Sonny Liston in a bruising and humiliating fight at Comiskey Park in Chicago. When he'd arrived at the airport in New York, he didn't know where he was going; he just knew he had to go somewhere, to escape. After arriving in the Spanish capital, the 27-year-old put on a fake moustache and beard, took a room in a cheap pension, assumed a limp, and pretended to be an old man. For several days he ate nothing but soup ... because he decided that an old man would only eat soup. Floyd Patterson hated soup.

Boxing has always had its fair share of eccentrics and head cases. Former middleweight champion Chris Eubank, for one, spent a good portion of the early 1990s dressed in jodhpurs and carrying a silver-tipped cane. Mike Tyson, for another, once threatened to eat the members of an opponent's family, and he bit Evander Holyfield on the ear. Twice.

But boxing has probably never known a champion as neurotic and unsure as Floyd Patterson. A sensitive man in a brutal sport, Patterson was famous for kissing an opponent on the cheek after knocking him out. He filled attentive sports writers' notebooks with musings about his self-doubt and his failings as a boxer and as a man. He was haunted by his losses and unconvinced of his victories. He had too much of the artist's soul to be a great champion, and he knew it.

In a 1964 profile of Patterson titled "The Loser," written by Gay Talese for Esquire magazine, the former champion described being knocked out by Liston as a pleasant, almost euphoric experience: "After Liston hit me in Nevada," Patterson told Talese, "I felt, for about four or five seconds, that everybody in the arena was actually in the ring with me, circled around me like a family, and you feel warmth toward all the people in the arena after you're knocked out. You feel lovable to all the people." Patterson was the perfect champion for a new generation of literary-minded sports reporters and magazine writers like Talese, who would ask athletes how they felt. The boxer was happy to oblige. He couldn't help obliging. Some writers started calling him Freud Patterson.

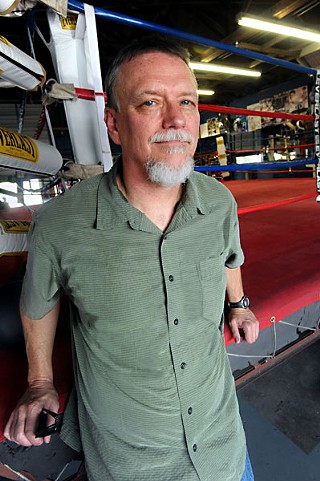

It was Patterson's conflicted character that drew writer W.K. "Kip" Stratton to him: "Floyd was paradoxical. On the one hand he was quiet and stayed out of the public eye. But when he got around journalists, he really explored his inner feelings in a way very few boxers had ever done. I found him fascinating."

Stratton is standing in the office of Lord's Gym on North Lamar, where former world champions Jesús "El Matador" Chávez and Anissa "The Assassin" Zamarron trained with Richard Lord for their title bouts and where Frederick Wiseman shot his brilliant 2010 documentary Boxing Gym. Every inch of the wall behind Stratton is covered in photos of famous boxers. A lifelong fan of the sport who has trained for more than a decade at Lord's, Stratton is explaining how he came to the decision to write his biography of the former heavyweight champion, Floyd Patterson: The Fighting Life of Boxing's Invisible Champion (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

"I was a kid during the golden era of boxing, right around when Patterson was fighting [Ingemar] Johansson, and I loved boxing," Stratton says. "I read a great quote from Muhammad Ali where he said that the four best boxers he ever fought were Sonny Liston, obviously; Joe Frazier, obviously; George Foreman, obviously; and Floyd Patterson. I was amazed by that. Not Ken Norton. Not Archie Moore. Not Larry Holmes. Ali said Floyd had the best boxing skills he ever faced. That quote is what really made me want to write a book about him. I wanted to go deeper into this character.

"After Floyd died in 2006, I was thinking about him a lot. He was largely forgotten by that point in terms of his cultural significance, but circa 1958 there were few Americans more well-known than Floyd. The heavyweight champion was that important. Soon after he died, I decided to write the book."

Some might say that Patterson (Stratton almost always calls him Floyd – a biographer's prerogative, I suppose) wasn't just forgotten but swallowed whole by historical forces and cultural agents with which he simply couldn't compete. First crowned the heavyweight champion in 1956 after knocking out Archie Moore, Patterson was at his peak at the tail end of one era and the beginning of another. He was a liminal figure, caught between the old way of doing things and the new – historically, culturally, even in his boxing technique.

"Floyd was an innovator but he was a transitional figure in many ways," Stratton says. Before anyone had ever heard of Cassius Clay, Patterson was bringing middleweight speed and movement into the heavyweight division, whose champions up until that point had all been thumpers and bruisers. It was a daring and revolutionary approach. But he didn't have the hand speed or the movement or the size to keep up with Muhammad Ali, who went from Patterson admirer to tormentor in just a few short years. When they finally faced each other in the ring in 1965, Ali embarrassed Patterson cruelly.

Ali's assault on Patterson didn't stay inside the ring, either. Patterson had been a hero to the black community in the late Fifties and early Sixties, both as a boxer and as a man. He was an outspoken supporter of the civil rights movement at a time when black athletes weren't supposed to be outspoken about anything. He stood with Martin Luther King Jr. and spoke in segregated Jackson, Miss., with Jackie Robinson, and he refused to defend his title in Miami until he got a guarantee that blacks would be allowed to attend the fight and sit where they wanted.

But what good was all that decency and humility and devotion to the principles of nonviolence and integration in the face of the racial and cultural turmoil of the 1960s and the overwhelming presence of a world-famous figure like Ali? Just as he had done with Patterson's boxing innovations, Ali took the older fighter's racial consciousness and developed it into something luminous, uncompromising, and indomitable. Ali was an avowed Black Muslim by the time he and Patterson fought, and he saw Patterson's NAACP affiliation, his faith in decency and fairness, and his overriding desire for acceptance from white America as signs of weakness and a slave mentality. He called him "Uncle Tom," and, for many in the black community in those turbulent years, the epithet stuck.

"In the Fifties, Floyd's work with the NAACP, his helping out in Mississippi with desegregation, the fact that he wouldn't fight in Miami unless the seating was desegregated – those were all huge things," Stratton says. "Joe Louis never would have spoken up about race. But by the end of his career, he was fighting a member of the Nation of Islam. He was a man who loved Nat King Cole, who suddenly found himself in the era of James Brown. All that fascinated me. I thought he was a great litmus [test] for America and the changes that were occurring very quickly at that time. Floyd has the reputation of a man swallowed up by events and personalities bigger than him, making him look small. But he really wasn't."

I ask Stratton, who lives in Round Rock and makes the trip down to Lord's at least three times a week, why he's so fascinated with boxing and boxers, and why he, like so many other boxing writers before him, trains in the sport himself. You rarely hear about football writers running the gridiron in their spare time. What is it about boxing that makes the Norman Mailers and the Ernest Hemingways and the Kip Strattons of the world want to live it, not just write about it?

"If Budd Schulberg were still alive I'm sure he'd say this – or ask Joyce Carol Oates – I've never met a boring person in a boxing gym. Everybody who does boxing has an interesting story," Stratton replies. He says sometimes he'll sit in the gym for hours and just talk to the other fighters, listening to their stories, the same way Talese and James Baldwin and A.J. Liebling would sit with Patterson through the night. "You get in here and the walls are down. I've been in the ring with Edwin Valero, training in the ring at the same time he was shadowboxing. An undefeated world champion who knocked everybody out, and I'm in the same ring with him. There's no way you could go work out with an NFL quarterback or hit a tennis ball with Roger Federer. But Norman Mailer sparred with José Torres many times. The walls are down in boxing."

W.K. Stratton will read and sign copies of Floyd Patterson: The Fighting Life of Boxing's Invisible Champion at BookPeople on Wednesday, July 11, 7pm.