Book Review: Drawing Interest

Books with graphic value

Reviewed by Wayne Alan Brenner, Fri., July 11, 2008

Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko

by Blake BellFantagraphics Books, 220 pp., $39.99

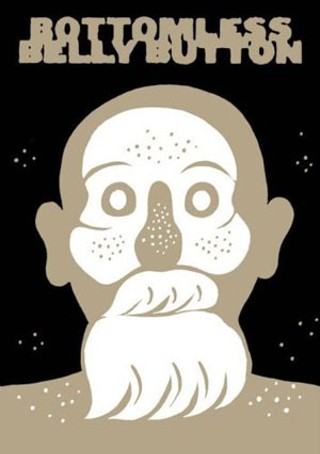

Bottomless Belly Button

by Dash ShawFantagraphics Books, 720 pp., $29.99 (paper)

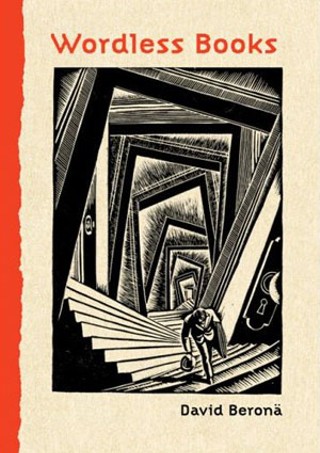

Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels

by David A. BeronäAbrams, 256 pp., $35

We've nothing against superheroes, per se, but the damned things are everywhere these days, as Hollywood's most recent extended fling with the cape-and-powers set continues to fill cinemas the way Bouncing Boy fills a spandex unitard. Time again, so we think, to highlight a few comic books that deal with subjects other than folks who are radioactively enhanced or genetically übercapable or whatever's the origin du jour. Time to champion the way artists can render our more quotidian vicissitudes with sequential graphics equal to the finest efforts in other media.

Before we shun the costumed do-gooders, though, let's tip our cocked fedora to Fantagraphic's gorgeous hardcover of Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, a thorough and critical biography by Blake Bell, which features so many pages of black-and-white and full-color panels from Ditko's decades-long and objectivist-tinted oeuvre that your eyes may need a day or so to recover. Unless, of course, staring into the non-Euclidean dimensions of Nightmare's realm or the burning face of the dread Dormammu is merely business as usual for your jaded peepers. Still, this collection of highlights from between the covers of Marvel's Dr. Strange and Spider-Man (and from numerous horror anthologies from Charlton Comics and Warren Publications and elsewhere) will certainly tweak your nostalgia glands and reinforce your appreciation for the artist's page compositions and panel arrangements, to say nothing of those distinctive hands and eyebrows.

Fantagraphics is also the publisher of the new Dash Shaw graphic novel, Bottomless Belly Button. As the title is derived from a substitution cipher within the story, let's play along mathematically and suggest that Shaw's artwork = John Porcellino x James Kochalka - Adrian Tomine, his writing the equivalent of Chris Ware + Chester Brown x Lynda Barry. That's a bit facile, sure, and nowhere near as difficult as the crafting of this phone-book-thick and deeply engrossing tale must have been. So many striking and original images, so many different characters presented in this story about what happens when the multi-siblinged Loony family gets together one last time at the family's surf-side home because the elderly mom and dad are divorcing after 40 years of marriage. The Loony family – ha ha, but it's not funny. This is a comic book in name only, yes, but don't think that it's bogged down with only tragedy and melodramatic hand-wringing. The book explores the effects the parental split has on the adult children and young grandchildren of the family, and on the parents themselves, in scenes of such familiar authenticity that you'll feel that argument-at-Thanksgiving sensation all over again and perhaps wake up the next morning with a nagging resentment and the beach's sand between your toes. The story explores more than that, though, as the characters' actions fractal out from around the instigating episode and develop into micronarratives of their own, beyond the family, beyond its dwelling. A house divided against itself cannot stand – as Lincoln said, paraphrasing Jesus of Nazareth – but the division of the Loony household, rendered in Shaw's disarmingly cartoonish style and with plenty of helpful diagrams, will likely stand as a classic in the years to come.

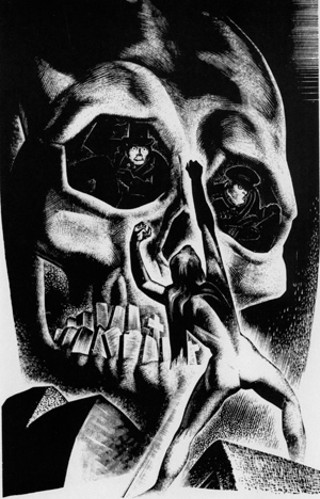

Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels comes to us from the prestigious house of Abrams, longtime publisher of art and illustrated books. This volume is David A. Beronä's academic but not dauntingly dry appreciation of books, from the first half of last century, that related their serious stories (of life in the Depression era, of vaudeville acrobats, of the atomic bomb tests in the South Pacific during World War II) in long and wordless sequences of woodcut images. Well, also in linocuts or lead cuts, sometimes, but always with fierce craftsmanship and the absence of text is the point. Frans Masereel's Passionate Journey (1919), Lynd Ward's Wild Pilgrimage (1932), and Laurence Hyde's Southern Cross (1951), among several others, are considered here in depth and generously represented by pages and pages of excerpted illustrations. These painstakingly created works – rife with images as powerful as any that came before or after – are the silent foundation that the best modern graphic novelists are building upon, and Beronä's considerations perform well in contextualizing and illuminating their monochrome wonders.