Twenty Flight Rock

The Summer Rock Roundup

By Jay Trachtenberg, Fri., July 20, 2001

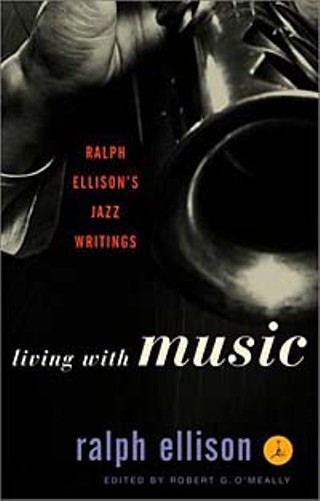

Living With Music

Ralph Ellison's Jazz Writingsby Ralph Ellison

Modern Library, 288 pp., $19.95

If you watched Ken Burns' Jazz extravaganza back in January, you may recall that some of the profound insights and exacting descriptions of its indelible contribution to American culture were taken from the written works of Ralph Ellison. Until now his various writings on jazz have appeared scattershot in a variety of volumes, most notably in Sense and Act. The publication of Living With Music makes readily available a cross-section of Ellison's music-related writings (jazz, blues, gospel, and even flamenco) culled from letters, interviews, magazine articles, short stories, and excerpts from his 1952 National Book Award-winning masterpiece, Invisible Man.

Ellison has always been forthright in acknowledging the influence of the jazz aesthetic on his own development as a writer. He came of age in the 1930s, at the artistic pinnacle of the swing era, and played trumpet in local dance bands. Not surprisingly, his heroes were Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie. Some of Ellison's most poignant writing in this collection are his reminiscings of young, fellow Oklahoma City residents, singer Jimmy Rushing and guitarist Charlie Christian, both of whom would move on to NYC and become jazz legends.

Ellison was one of the most revered and original voices in jazz criticism of his day. More importantly, he was among the first to extoll the dignity of African-American musical expression in its own right as a truly indigenous American art form, as opposed to its frequent perception as merely lowbrow entertainment.

Ellison was present for the germination of the bebop revolution; it is fascinating to read his first-hand account of the hothouse process taking place in jam sessions at Minton's in Harlem. He was not, however, in the least bit enamored by the resulting "revolutionary rumpus" that bebop brought to jazz, nor by its preeminent purveyors, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and their followers. Later, in a letter to friend Albert Murray, he expresses his disdain for jazz modernists with a Newport Festival reference to "that poor, evil, lost little Miles Davis" and his bandmate John Coltrane's "badly executed velocity exercises." Depending upon your vantage point, history has been far kinder than Ellison's assessments.

As for the blues, he often addresses the topic somewhat indirectly within the context of his fictional characters, eloquently portraying the blues as a depiction of both the harsh realities of life and the optimism of overcoming those travails. Relatedly, Ellison is scathing in his review of Blues People, Leroi Jones' (now Amiri Baraka) socio-musical take on "the Negro experience in white America" as interpreted through the prism of the early Sixties civil rights era.

With his impeccable standing in the intellectual community, Ellison's countering of these progressive thinkers is a bit surprising at first but ultimately he provides us with much-needed food for thought and perhaps even some basis for re-examination of our previously accepted views.