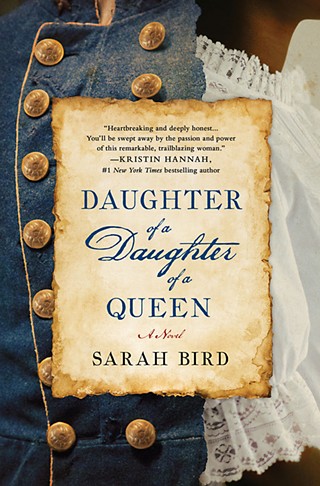

Book Review: From Slavery to Buffalo Soldier in Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen

Sarah Bird's historical novel tells one woman's unique tale of freedom

Reviewed by Marisa Charpentier, Fri., Oct. 5, 2018

What's most impressive about Sarah Bird's latest novel isn't just the fact that it resurrects the 150-year-old tale of the only female soldier to serve with the storied Buffalo Soldiers (based on what little documentation exists today), or that it's jam-packed with wit, action, and adventure. It's the fact that on top of all that, Bird weaves in a moving and tender love story. But that's just one of the many complexities she executes smoothly in her thrilling new novel, Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen.

The book is loosely based on the true story of Cathy Williams, who grew up a slave on a Missouri plantation before the Union army took her away to work as a cook during the last years of the Civil War. After the war, she disguised herself as a man by the name of William Cathay to join the Buffalo Soldiers, African-Americans who fought off Native Americans and protected settlers in the peacetime U.S. Army.

Cathy's voice is intriguing from the start. A white author, Bird took a risk writing an African-American woman in the first person, as this raises questions about cultural appropriation. The actual narration, though, doesn't sound like Bird is stealing Cathy's struggle; rather, it's highlighting her achievement. This is first and foremost Cathy's story. Writing in the first person gives Cathy's voice back to her.

In the first line of the book, Cathy tells the reader, "I am a daughter of a daughter of a queen and my mama never let me forget it." Her royal blood was passed down from her "Iyaiya," her grandmother who was a warrior queen in Africa with teeth filed to a point that could tear an enemy's throat out. For Cathy, this ancestral detail – an imaginative flourish Bird envisions for the protagonist – is important. She does not see herself as a slave. She, like her grandmother who was stolen away from her homeland by white men, is a captive. Cathy's warrior-woman descent serves as motivation for her throughout the novel as she faces physical and emotional torment.

And that torment comes from all directions. First, there are the challenges Cathy faces as a black woman in a white man's world, and more specifically, a white man's war. As a black soldier, she faces discrimination from white generals who don't trust and respect their African-American counterparts. Then within the barracks, surrounded by other black soldiers, Cathy is subjected to "locker room talk" that sends fear through her body. She's very aware of the horrible things the men would do to her if she were found out to be a woman. And when finally seen for what she is – a black female soldier who fought with the best of 'em – few give her the recognition she deserves.

But Cathy is cunning and the true moral center of the story. She can throw out quick-witted, snarky comments to her hotheaded comrades and cleverly finds ways to appear manly (namely, shaving her face and fashioning a teapot spout to give the illusion that she can urinate alongside men who aren't shy to relieve themselves publicly). She's skillful, too. She happens to be the best shot in the crew. The irony of formerly enslaved people planning to subdue another race – Native Americans – is not lost on Bird and certainly not on her protagonist. Cathy is quick to recognize the hypocrisy in how the Buffalo Soldiers vilify Native Americans for torturing white settlers, although white men had conducted similar tortures on their black slaves.

That hypocrisy points to the complex question at the heart of the novel: What is freedom? At first, Cathy thinks maybe it lies somewhere in her choice to join the military. Riding through towns in her blue uniform after the war, she feels safe and superior, as white folks watch the black soldiers pass. Still, she's at the whim of her white generals. Maybe freedom lies in the end of her hitch, or maybe it lies in what Buffalo Soldier Sergeant Levi Allbright, Cathy's love interest, says: "We're broken men. We have to create a new generation built from the ground up of strong, capable men, true and brave." In the end, they wonder, maybe true freedom isn't possible in the U.S. at all.

The smelly barracks of an Army outpost seem a strange place for a love story to blossom. But the one Bird imagines for Cathy doesn't feel out of place. Instead, it adds depth to Cathy's character. Though the way Cathy meets her love interest seems pretty improbable, the subplot allows Cathy to free herself from her feigned masculinity and explore her womanhood to its fullest extent. At no point does she become dependent on this relationship – Cathy is certainly no damsel in distress. In the end, it is being all of what she is – strong, persistent, and overflowing with love – that makes her great. While she may not have been able to openly be a resilient and passionate female soldier in real life, Bird's resurrection of Cathy allows her to brazenly and boldly be all these things and more. Maybe that is a form of freedom.

Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen

by Sarah BirdSt. Martin’s Press, 416 pp., $27.99

Sarah Bird will be the featured guest at Evening With the Authors, a benefit for the Dr. Eugene Clark Library, Sat., Oct. 6, 6:30pm, at 509 S. Commerce St., Lockhart. For more information, visit www.eveningwiththeauthors.com.

Bird will also speak at the Chez Zee Author Series, Wed., Oct. 17, 6pm, at Chez Zee American Bistro, 5406 Balcones, and will appear at the Texas Book Festival Oct. 27 & 28.