‘Press Forward’

Two exhibitions capture printmaking's experimental drive

Reviewed by Robert Faires, Fri., Jan. 14, 2011

Picture yourself in a laboratory outside of time where bustling among the beakers and Bunsen burners and computers and microscopes are Alfred Nobel, Louis Pasteur, Marie Curie, Enrico Fermi, Linus Pauling, and Ahmed Zewail. There you stand with some of the groundbreaking figures in chemistry, people whose persistent experimentation led to discoveries that deepened our understanding of this existence we share. And in this extraordinary space, you have the opportunity not only to appreciate anew their accomplishments as individuals but to see what they've achieved collectively on a continuum of centuries, in which one breakthrough has built on another over and over and over again, driving forward the development of the field. And because all these great chemists are there together, you get to catch them conversing with one another, to witness the interplay of ideas and influences among these innovators.

That's very much the feel that comes from viewing "Repartee: 19th-Century Prints & Drawings From the Blanton's Collection" at the Blanton Museum of Art and "Advancing Tradition: Twenty Years of Printmaking at Flatbed Press" at the Austin Museum of Art – Downtown, especially seeing them back-to-back. The two exhibits create a strong impression of printmaking as an art form in constant development, restlessly pushed forward by the experiments of its artists. Now, all artists experiment, and every medium in the visual arts can claim its own innovations through the past 200 years. But there's something distinctive in printmaking's ties to the mechanical and the chemical; its expansion of techniques corresponds to the advances in technology and science through the 19th and 20th centuries more than the traditional mediums of painting, drawing, and sculpture. It shares that with photography, and just as the Ransom Center's recent showing of photographs from its Gernsheim Collection documented that form's progress through experimentation with chemicals for developing images and changes in equipment, "Repartee" and "Advancing Tradition" reveal how printmaking has evolved from monotone woodcuts and etchings on paper to vibrantly colorful works that may blend multiple methods – intaglio, aquatint, photogravure, monotype, screenprint, lithograph, drypoint – sometimes with assistance from digital manipulation and ink-jet printing, sometimes printed on alternative materials such as felt, and sometimes incorporating sculptural elements such as wood, string, or, as in the case of Liliana Porter's Situation With Dog, an inch-high plastic bridegroom.

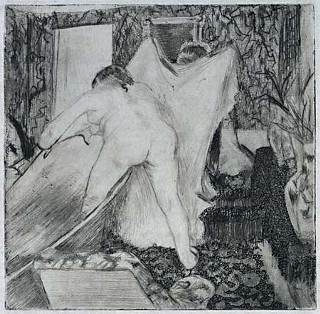

Actually, that sense of progression was built into "Repartee," since the Blanton created the exhibition as a companion piece to "Turner to Monet: Masterpieces From the Walters Art Museum." Like that popular touring show, "Repartee" marks the changes in artistic styles and subject matter among Western European and American artists as cultural shifts took place throughout the 19th century. The rural increasingly gave way to the urban, the classical to the impressionistic, the ideal to the specific, the formal to the personal, and, some would say, the high to the low. The developments are easy enough to see as you move through "Repartee." Take, for instance, the approach to the feminine form: In the first room of the exhibit, you have Théodore Chassériau's Venus Anadyomene, a lithograph on chine-collé from 1841 after his successful painting. She's the romantic personification of beauty, with the gentlest of curves defining her slender nude form everywhere: her breasts, her hips, her belly, the nape of her neck, the small of her back, the hollow behind her knee, the arch of her foot, and, of course, the long locks of wavy hair that cascade down her back like a waterfall. Chassériau's approach is softcore classicism, with the goddess' full-frontal exposure offset by her demurely downcast gaze and the downy edges and smooth shadings that are about as close as lithography can get to a soft-focus lens. Compare that to Edgar Degas' La sortie du bain (1879-80) in the fifth room. The impressionist also depicts a naked female figure emerging from the water, but this one is an oddly graceless figure, caught half in, half out of the bathtub, awkwardly bent over and clutching the sides as she attempts to extricate herself. Our view is from the back, and Degas doesn't even let us see her face; rather, it's her blockish posterior that commands the center of the frame. In four decades, we've moved from woman as the feminine divine to the feminine mundane, from the ethereally flawless face to the earthbound, overfleshed ass.

The evolution of form and attitude goes still further when carried over to the Flatbed Press retrospective at AMOA. Some 120 years after Degas' prosaic portrait, Bob Schneider – yes, that Bob Schneider – took the female nude to the extravagantly fantastic, with most of the flesh seemingly cut away, exposing internal organs and networks of veins but also strange miniature figures, elaborately patterned shapes, a face behind the external face (or mask), and a snake attached to/coming out of one arm. Rendered in razor-thin lines, starkly graphic, the picture is something of a Boschlike underworld contained within a human outline, propelling woman beyond the celestial and the domestic into a realm dreamlike and primal – the feminine mythic. Taken together, the three prints – all by men, it's worth noting – create an intriguing conversation about how women have been and are viewed by society and how that has played out in their representation in art.

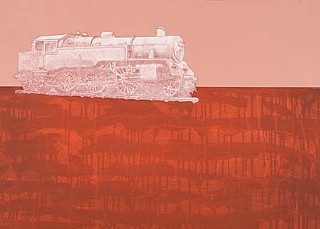

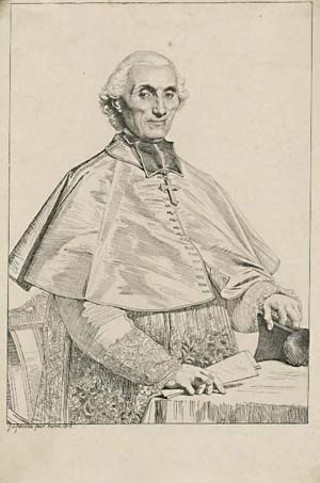

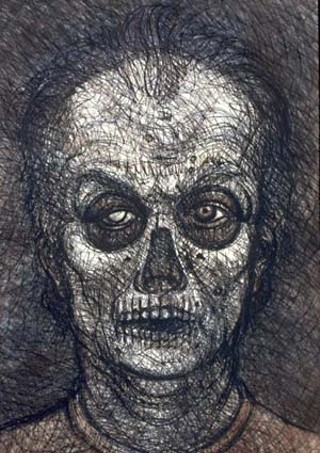

Such interplays can be found throughout "Repartee" and "Advancing Tradition" – say, the contrast in portraiture between J.A.D. Ingres' 1816 etching of Gabriel Cartois de Pressigny and Luis Jiménez's 1996 Self-Portrait, with the former cool and clean, a formality in the delicate line-work befitting the ornately robed cleric, and the latter raw and sketchy, a baroque tangle of lines that speaks to the artist's rough edges almost as much as the skull he shows through his features. In 1836, war could be celebrated in art with images of military prowess and order, as in Denis Auguste Marie Raffet's La Revue nocturne (The Night Review), with its lines of regimented cavalry, the horses spaced almost mathematically, the riders' swords held up at nearly identical angles – the very picture of martial discipline and conquest. But in the wake of the 1871 civil war in France, Édouard Manet represented the conflict with the image of a dead militiaman lying on a street before a broken wall, the thick, dark lines and heavy shadows on the still form in striking contrast to the soft shades of gray cloaking Raffet's valiantly charging troops – a shifting view of war from the heroic to the tragic. And in 1991, the shift went to the grotesquely comic, with Robert Levers' Victory: The Celebration commemorating the first Iraq War with a military man of some sort running toward three soldiers, all of them skeletons in uniform. Now the grimly thick marks of Manet's are describing cartoon figures, with grinning skulls and lines descending from above the frame to the figures' wrists and feet, suggesting the strings that manipulate marionettes. Here, what you're seeing isn't so much a progression in the sense of one attitude supplanting another – all three images just described still speak to some truth about war – but a moving current of perspectives, shifting with the events of history. And as in our hypothetical laboratory, the exhibitions enable us to take the long view, to see the continuum of responses and compare them to one another, for what they have to say and how they say it.

And how they say it is perhaps the greatest pleasure of "Advancing Tradition." The show is dazzling in its array of styles and modes of expression: simple graphic representations of nature, human figures, dense abstracts, photographic images, rendered text, eye-popping in their colors and textures. And that's a testament not only to the artists themselves but to Katherine Brimberry and Mark L. Smith, the powers behind Flatbed Press. They might just as easily have named it Flatbed Research and Development Institute, because the printmaking facility has made it a mission to find ways to put the images in the heads of the artists they work with onto paper (or paper bags or felt or whatever surface they want). And that means being inventive, trying the unconventional, taking risks, experimenting. "Repartee" shows us how that tradition was established in Europe and carried through the Industrial Age to the advent of modernism; it gives us the past. "Advancing Tradition" shows us how that tradition has been built upon in our own time and city; it gives us the present – but it doesn't end there. What we can see in its two decades of expansive variety is an innovation engine that is still driving forward, a lab still working toward the next advance, the next new expression. It also gives us printmaking's future.

"Repartee: 19th-Century Prints & Drawings From the Blanton's Collection" runs through Jan. 16 at the Blanton Museum of Art, Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard at Congress Avenue. For more information, call 471-7324 or visit www.blantonmuseum.org.

"Advancing Tradition: Twenty Years of Printmaking at Flatbed Press" runs through Feb. 13 at the Austin Museum of Art – Downtown, 823 Congress. A Flatbed Artist Reunion, including a Q&A with artists who have worked at Flatbed through the years, will take place Saturday, Jan. 29, 2pm, at AMOA – Downtown. And a concert featuring printmakers/musicians Bob Schneider and Terry Allen together on stage for the first time will be held Saturday, Jan. 29, 8pm, at Antone's. For more information, call 495-9224 or visit www.amoa.org.