Setting the Table

New Director Ned Rifkin wants to bring more people to the feast that is the Blanton

By Robert Faires, Fri., Oct. 2, 2009

What's a former undersecretary of art for the Smithsonian Institution doing running the Blanton Museum of Art? And how does one shift from the nation's capital to the Texas capital? That's what we wanted to know from Dr. Ned Rifkin, who in May was named successor to Jessie Otto Hite, who ran the Blanton for 15 years, and interim Director Ann Wilson. So the Chronicle spoke with Rifkin about returning both to the Lone Star State (he taught at the University of Texas in Arlington in the Seventies and directed the Menil Collection in Houston from 1999 to 2001) and to the classroom (his duties include a professorship in the Department of Art & Art History and advising President William Powers Jr. on matters of art), as well as his reasons for taking the Blanton post and his plans there. This Sunday, when the museum is adding a new feather in its cap of international renown with the opening of "Paolo Veronese: The Petrobelli Altarpiece" (see "Putting It Together," below), it seemed especially fitting to run his answers.

Austin Chronicle: Looking back on your experiences at the Smithsonian, what happened there to shape the philosophy that you're bringing here?

Ned Rifkin: Well, one thing that's great about the Smithsonian is that America comes to the Smithsonian – it's almost a theme park about American civics and history and art and science and so on. So people are hungry – really, really hungry – for seeing things, whether it's the ruby slippers that Judy Garland wore or Archie Bunker's chair or a Rothko painting. They really want to experience the real thing on some level, and they're willing to make the pilgrimage on the National Mall. So what I've learned from that is that – it's like, if you put out good food, they'll eat. They'll really eat. And whether they're the students who have their one trip to Washington, D.C., for school or whether it's the grandparents bringing their grandchildren or the adults, they really understand the value of setting aside time to step into something that really illuminates and inspires. People used to come up to me wherever I was – literally, in the world – and say, "You work for the Smithsonian," and it was in this kind of reverential tone. It was not because I am the Smithsonian; it was what they experienced. What I learned was you can be meaningful to people on so many levels, and it starts with what you actually do on site, and it emanates from there. So what are the ways we can touch people? What are the ways we can become a state of mind as well as a place, a feeling, and I'll say a resource rather than an attraction, because I think people are very hungry for nourishment, more and more during these very difficult times that we're experiencing now.

AC: When you left the Smithsonian, you told The Washington Post that you were going to be very careful about what your next job was. So what was it that you saw in this job that made it feel like something different from what you had there? NR: I don't know the quote you're referring to, but it does reflect fairly well that I had to think about what I wanted to do after being an undersecretary of the Smithsonian, which is a big deal. I realized that part of what I wanted was a more intimate and more educationally focused environment. And when this job came up, it seemed to offer me the opportunity to be both a teacher and learner and a leader, which are things that I value immensely. Leadership is something that I think has been highly questioned in our country and within the world. My view is that ultimately it's about your own values and how to extrude them through what you do into something meaningful, some sort of embodied practice. Teaching is where I started, and in a funny way I never left, because I always thought that the museum was an instrument for teaching. It was many other things, but it was certainly about enabling people to learn how to see actively. And it's not just about art. If you look at a portrait, maybe you'll think about looking at people differently. If you look at a landscape painting, you may perceive nature differently, and so on and so forth. I felt that maybe it was time to share [the experiences and skills that I've accumulated] in a meaningful way with people who are coming together as a community to learn.

So my feeling is that Austin, which has become an almost critical-mass place for creativity and culture, and the University of Texas, which has, over the decades I've known it, become one of the top universities in the country – the convergence of those two things made me feel: I can learn, I can grow, and I can become more of who I am in this situation, and in so doing perhaps ignite somebody else's quest and really motivate [someone].

AC: Where did the resources of this museum fit into the appeal of the job for you? I'm thinking of the Suida-Manning collection, the Steinberg print collection, having two new buildings ....

NR: The resources, as I see it, have to do with people and not just the objects. While I was being interviewed as a candidate, I was meeting outstanding people who were clearly dedicated and devoted to the same values that I share, right up to the president and beyond him to the support system: the museum council people I would meet, the community collectors that I was able to get in touch with. With a new facility and acquisitions that have been made already, the Blanton has reached what I would call a threshold moment, and that really is attractive to me. It's brimming, and I want to be part of that. I want to be part of that team. I want to be a leader. A leader is not just somebody who's in charge; it's somebody who understands the energy and the potential of the people and the resources. And the university as a resource is so incredible. There are so many extraordinary people here, with not only collections but also knowledge and expertise, insights. It seems to me that the more we can cross-pollinate and collaborate, the richer the offerings will be. I think I said something about nourishing people. You know, there's a way to set the table, and when you set the table in a way that's attractive and put out really good food, it's gonna get eaten. The experience isn't just getting the nourishment; it's the pleasure of eating, the aroma – all these things are part of the experience. There have to be hors d'oeuvres, and there has to be dessert, and the entrée is the building and the collections. But the rest of it is just as important, you know, including how you invite people and welcome them to your home for art.

AC: To me, it's been fascinating to watch how this particular institution has pushed itself to welcome people through less traditional means, such as the B Scene and the community programs with "Birth of the Cool." They've done so much to make that town/gown barrier porous and get people more excited about crossing back and forth.

NR: There are certain times when you say: "It's not either/or. It's both/and." There's no reason to have to perceive things as separated. I understand that historically there's been a sense that the university is somehow insular or boundaried, but I think art is the perfect vehicle for transcending it. I also think that in a day and age when people are communicating with each other at great distances and with great rapidity and speed, this is a place of coming together, of intersection, of fusion, and you need to become the town mall, the commons. You need to be the promenade, the place where socially people really want to go and be, not because it's trendy, but because it is so rich. Museums serve many different functions, and one of them is social gathering. And it's secular. It's not religious, but where it becomes like a church or a temple or a mosque is that there's something reverential and spiritual sometimes about being knocked out by a work of art. You know, it's hard to say what you think or feel. It's just incredible. And when you have that experience, it is like an epiphany. It is the realization that I am communicating with someone who's centuries old or far away or maybe around the corner but they're not right here except for that amazing thing, which is essentially the proxy for that person, standing in for that person, and you touch something and they touch something in you that becomes activated, animated. And so it's vital. It's vibrant. It's alive in a way that, you know, if you just roller-skate past it, it's not gonna happen. And you're not going to like everything, and in fact, if you go to a party, you don't like everybody at the party, but you have that one, extraordinary, deep conversation that makes that evening totally worthwhile. So we're talking about those kinds of experiences, ultimately.

Putting It Together

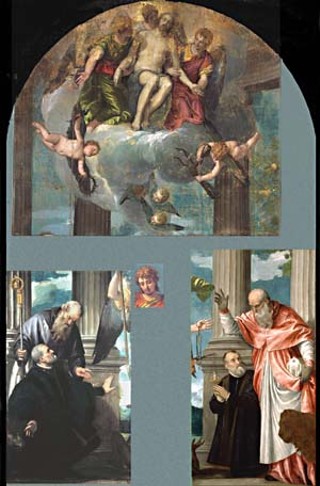

Dr. Xavier F. Salomon knew he was on to something, something big: the location of a lost section of a massive 16th century Italian altarpiece that had been hacked apart and sold in sections 220 years ago. Based on the three surviving fragments, it was clear that at one time, the Petrobelli altarpiece – a 20-foot work commissioned from the Venetian master Paolo Veronese for the church of San Francisco at Lendinara, near Padua, Italy – included a figure of St. Michael between the kneeling figures of Antonio and Girolamo Petrobelli, the cousins who had commissioned the piece. Since at least the 1930s, though, scholars had assumed the figure was simply destroyed when the work was cut into pieces. But while Salomon had been in Lendinara doing research on the painting, the question of what had happened to the angel kept nagging at him, and he wondered if perhaps the head might have been preserved. Then, in London, where he serves as curator of the Dulwich Picture Gallery, in the middle of the night it came to him: He'd seen the head of St. Michael in Austin. Touring Texas the year before, he had stopped by the Blanton Museum of Art to see the three works by Veronese that were part of its Suida-Manning Collection of Renaissance and baroque art. One of them was the head of St. Michael. Only no one knew it was St. Michael; it was listed in the collection only as Head of an Angel, which was what art historian William Suida thought it was when he acquired it in the 1930s. That's when Salomon e-mailed Jonathan Bober, the Blanton's curator of prints, drawings, and European paintings, and asked him to check the dimensions of the head of the angel and the character of canvas. If Salomon's hunch was right, he had solved a centuries-old mystery in Renaissance art. Bober gave him the data. They matched those of the Petrobelli altarpiece. To remove all doubt, Bober took Head of an Angel to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, which holds the upper section of the altarpiece, Dead Christ Supported by Angels. With an X-ray test and by positioning the Blanton's painting with the National Gallery's section, conservator Stephen Gritt was able to confirm Salomon's hypothesis.

This year, all four surviving fragments of the Petrobelli altarpiece were reunited for a special exhibition, "Paolo Veronese: The Petrobelli Altarpiece." The show, which also includes X-rays of the sections of the altarpiece, first opened in the Dulwich Picture Gallery in February. This week, it opens at the Blanton for a four-month stay, its only showing in the United States.

"Paolo Veronese: The Petrobelli Altarpiece" will be on view Oct. 4-Feb. 7 at the Blanton Museum of Art, MLK at Congress. For more information, call 471-7324 or visit www.blantonmuseum.org.