What Can a Century Tell Us?

Looking at two art exhibitions that both survey 100 years of imagery, the more things change ...

By Robert Faires, Fri., July 13, 2007

One hundred years can be an intimidating span of time.

It's more time than most of us will ever live to see. It encompasses generations. Go backward from our own, and you'll reach our great-grandparents, perhaps even our great-great-grandparents – ancestors whom most of us never met. And so much happens in a century – it's the span from the Wright Flyer at Kitty Hawk to Voyager 1 passing the edge of the solar system – that when you try to wrap your head around it all, it can set your mind reeling.

Thus, when two separate art exhibitions arrive in town boasting a century's worth of images each, it's only natural to feel a little cowed. Can one's visual senses even absorb, much less appreciate, all the artwork of 100 years? Well, if they really had to look at work that covers all of a century's major artists and movements, across all cultures and media, maybe not. But fortunately (for our overworked modern eyes, anyway), neither of these shows claims to be comprehensive; rather, each offers a representative look at a particular kind of artwork through the lens of a nicely focused collection. The Blanton Museum of Art's "A Century of Grace" draws from the holdings of New York's Dahesh Museum of Art, which includes works by artists who trained in the academies of Europe in the 19th and early-20th centuries; the Austin Museum of Art's "The Target Collection of American Photography: A Century in Pictures" is culled from the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Both shows are extremely manageable – each covers its respective 100 years with fewer than 100 works of art – while still managing to convey a sense of the epic time frame during which these images were created. And in the way they do that, they allow us to glimpse the impact of that long stretch of years on art and its making.

With "A Century in Pictures," we see an art form inventing itself, photography evolving from an almost purely documentary medium into one as expressive and versatile as any of the visual art's more traditional mediums. "A Century of Grace," by contrast, allows us to see one of Western art's centuries-long traditions – representation of the human figure – in a crucible of change, tested by the rapid expansion of industrialism and European imperialism, as well as developments in science and social attitudes. These progressions aren't laid out for us in linear fashion in either show. The curators for both exhibitions – Anne Tucker for AMOA and Cheryl Snay for the Blanton – forgo a strict chronological layout in favor of small groupings that relate to specific types of work or developments on the scene. In Snay's case, that means sections devoted to drawing (traditionally the foundation for figurative work), the academies (the accepted training ground for artists), and dominant genres of the day (mythological/allegorical images, religious scenes, domestic images). In Tucker's, it means groupings by documentary work, portraiture, landscapes, abstracts, and experimental imagery. With this approach, you might miss some of the simple satisfaction that comes from following the advancement of these art forms year by year, decade by decade, through their respective centuries, and getting a grasp on who was contemporaneous with whom requires some effort, but you can sense perhaps more keenly the variations taking place within certain movements or ways of working – the shift in landscape photography from only natural settings to massive man-made structures as well, for instance. And both curators set works side by side that give an illuminating nod to time's passage, as with Snay's placement of Jean-Léon Gérôme's 1849 Michelangelo Showing a Pupil the Belvedere Torso, painted when the artist was 25, next to his Working in Marble, painted 41 years later. Being able to compare the work of the young and mature Gérôme is fascinating, especially since both depict artists and statues. To these eyes, it's the sculpture that feels more alive and convincing in the earlier work, the flesh that does in the later work.

Even without a timeline, the times make themselves felt in both exhibitions. Snay devotes a section to Orientalism, the movement fueled by Western Europe's imperialistic drive into the Near East, Middle East, and North Africa. In the first half of the 19th century, Europeans' awareness of the cultures of these lands was expanded to a whole new level, and they were captivated by the exoticism of the other. Artists – some of whom traveled to these regions themselves – made it the subject of many works, rendering it in extravagant style. The exposed flesh that dominates other sections of "A Century of Grace" is all but invisible here, the bodies swathed head-to-toe in thick fabrics with brilliant colors and rococo patterns. There's something so deliberate in the depiction of this foreignness as to give off an almost palpable sense of social trend and fashion.

That's more true of "A Century in Pictures," where shifts in dress and hairstyles are apparent throughout, as are significant moments in the historical record. Here's the Great Depression, as captured by Dorothea Lange in her South-in-a-nutshell Plantation Overseer (1936) and Russell Lee in his telling domestic scene FSA Clients at Home, Hidalgo County (1939). And there's the space race, represented by a surprisingly artful image by astronaut Pete Conrad of his Apollo 12 colleague Alan Bean collecting lunar samples on the surface of the moon. (The composition has a beautiful balance to it, and the sharp contrasts of sun-drenched spacesuit and inky lunar sky are hypnotic.) Of course, telling us the time is the nature of the medium; photography was developed to record the world around us. But beyond the physical history documented here, there's also a sense of the spirit of the times in parts of the AMOA exhibit – specifically, the experimental spirit that characterized the Sixties and the search for identity and equality that reached a new prominence in that decade. Tucker includes several images that explore gender issues for women, and they're among the most daring in the exhibit, in terms of pushing the form. You have images split or replicated or assembled in a collage. You can almost feel a restlessness in the photographers as they seek new forms of language to express new attitudes in society.

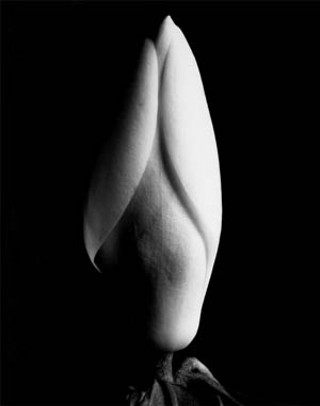

In a sense, that attitude pervades "A Century in Pictures." Here's this new art form, the show shows us, with artists flooding to it to see what they can do with it. And it turns out they can do everything with it: capture history, make portraits, isolate elements of the world into abstract forms, make images about making images. It points up the restless curiosity of the race, our incessant drive to explore and discover, as well as to change and transform. In that sense, "A Century in Pictures" is the more exhilarating of the two shows. Again and again, its images seem to be racing forward, testing the form's limits, taking it – and us – places we've never been before. As you leap from Eadweard Muybridge's stunning panorama of 1877 San Francisco (an image to thrill the historian in you) to Imogen Cunningham's breathtakingly elegant close-up of a magnolia bud (1925) to Weegee's riotous candid shot of two teens smooching at a 3-D movie (so much of its time – the Fifties – and so thrillingly of the moment) to Joan Lyons' politically charged split image of a young woman in 1977, the variety and energy of the works generate an underlying buzz in the exhibition that seems fitting for the century it documents. Here we are, being propelled faster and faster through the world, in automobiles, in aircraft, on electronic impulses, and our art is keeping pace.

"A Century of Grace" can't offer that kind of velocity rush from the technological drive of the past 100 years, but then it isn't even trying to. As its title makes clear, this exhibit intends to turn the clock back to a point when time wasn't so much of the essence, when an artist's energies were invested in studying form and steeping in tradition, the better to render the human form with the utmost of refinement, of beauty, of grace. What binds the show together is not so much what changes over the broad expanse of the 19th century as what doesn't change. Across the gallery, from drawing to sculpture to painting, from biblical illustration to orientalist portrait to scene of country life, the figures share the same sensuous curves, no matter the decade. The limp body of the crucified Christ in Paul Delaroche's Lamentation from 1820 boasts the same delicate arcs and voluptuous turns along his form as the hunched bather in Jules Dalou's bronze cast eight decades later. Position yourself at the entryway to the gallery with "Master Drawings From the Yale University Art Gallery," and you can take in both Jean-Jacques Pradier's Standing Sappho, circa 1850, and Adolphe-William Bouguereau's The Water Girl, painted in 1885, in a single glance. Despite the differences in medium and genre, you can see that same elegant tilt of the hip, the same blissful slope to the shoulders, the same smooth curve to the jaw and line in the arms, the same weight in the left hand where it rests. Turn your head to the left until you can catch Joseph Bail's A Letter From His Father – an image that in its down-home character and execution seems to anticipate Norman Rockwell – and you might see in the farm boy's swaying back an arch akin to Sappho's. It's like that throughout the exhibit: the arch of a back, the ripple of muscles under a forearm, the arc of an instep, the crook of an arm, the bend of a leg – curves echoing one another, connecting work to work to work in a way that shows how constant our view of the human form is and how deep our desire to depict it is. To see that endure across a span as intimidating as a century is both lovely and inspiring.

In some ways, the shows both reinforce the idea of how much remains constant beyond the confines of a lifetime or passage of generations. In "A Century in Pictures," Anne Tucker has placed side by side two landscapes, one by Ansel Adams and one by Lynn Davis. Adams is rightly considered one of the great masters of the form, and Winter Sunrise, Sierra Nevada shows why; he's caught the Western range at its most monumental, rising brightly into the heavy sky, towering like a primeval giant over a pasture still sunk in darkest shadow. Adams made that image in 1944, the year that Lynn Davis was born, and now an image of hers sits next to his. Sun Set/Ocean also captures nature in all its vastness: a broad gray expanse of water under a great lowering sky, with a small white orb suspended between the two. The photographs complement each other, not only as portrayals of the day at its beginning and at its end but as parts of one tradition, the grand natural landscape. They were made a half-century apart, but they share the same sky, that same sun, the same view of nature. It's a sign that much may change over 100 years, but some things endure: the vault above, the earth below, our impulse to celebrate what we see, to record it and transform it and treasure the view.

"The Target Collection of American Photography: A Century in Pictures" is on display through Aug. 12 at the Austin Museum of Art, 823 Congress. For more information, call 495-9224 or visit www.amoa.org.

"A Century of Grace: 19th-Century Masterworks From the Dahesh Museum of Art, New York" is on display through Aug. 5 at the Blanton Museum of Art, MLK at Congress. For more information, call 471-7324 or visit www.blantonmuseum.org.

A free public lecture, The Nude and the Lewd: Alexandre Cabanel and the Birth of Venus, will be presented by Lisa Small, associate curator for the Dahesh Museum of Art, on Sunday, July 15, 2pm, at the Blanton.