Katrina: The Girl Who Wanted Her Name Back

The play 'Katrina: The Girl Who Wanted Her Name Back' seeks to honor the New Orleanians affected by Hurricane Katrina, but the level of intensity in the UT staging often makes it hard to connect to

Reviewed by Robert Faires, Fri., Oct. 20, 2006

Katrina: The Girl Who Wanted Her Name Back

Oscar G. Brockett Theatre, through Oct. 22

Running Time: 1 hr, 20 min

Bad enough to be named Katrina when a hurricane called that drowns New Orleans – it's like guilt by association, a stain on your own being because you share the same name as this devastating force of nature – but to be in that city when the storm hits? That's a nightmare, fighting for your very life against this thing that's stolen your identity. Small wonder then that the young heroine of this new drama by playwright Jason Tremblay seethes with frustration and rage. She's stuck in the storm-blasted city, stuck in the heart of the hurricane with two elderly people – her aunt and a neighbor – both in wheelchairs, stuck with this name that's now become hateful to everyone who hears it.

Being stuck and working out how to move on is a lot of what Katrina: The Girl Who Wanted Her Name Back is about. In it, Tremblay, a third-year MFA playwriting student in the UT Department of Theatre & Dance, is paying obvious tribute to the New Orleanians who were physically stranded by the floodwaters and fought for their lives and the life of their city in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, but his play also explores what getting stuck means in other aspects of our lives. While the girl Katrina is seeking refuge from the storm with her Aunt Beulah and Mr. Thibeaux, she encounters the ghost of a boy who died in a Storyville fire a century before. He is stuck between this world and the next, still carrying the burden of wrongs he did to a friend during his brief life. Meanwhile, Katrina's father, from whom she was separated during the hurricane, is stuck trying to find her; no matter who he asks or where he turns, he can't get a clue to her whereabouts. Moving through helplessness, through hopelessness, through anger, through despair, through grief, through fear of death, through fear of life – these are the challenges faced by Tremblay's characters, in a roar of wind and water that Lear would shrink from.

You expect intensity in a play about the storm Katrina, so it's fitting and right for the characters suffering through to cry out and argue and rail. But when the actors portraying those characters play into that intensity to the degree that they frequently do in this Department of Theatre & Dance production, consistently pitching lines and even whole speeches at the level of, well, a raging tempest, it can keep the characters at arm's length from the audience rather than drawing us closer to them. We experience their turmoil only on the surface rather than at a depth of feeling that would resonate most strongly with us. And what makes that lack of connection doubly disappointing is that not only are the actors all appealing, but we want to connect to the people they play. The wound that this tragedy left on our hearts is still fresh, still tender, and we are open to a play that seeks to honor that, as it's clear that this play and this production and everyone connected with it seek to do. Unfortunately, much of the time it feels like director Jonathon Morgan, his cast, and the other artists involved are, like Katrina's characters, stuck in one place that's hard to get through.

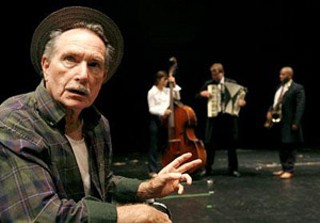

By the play's end, however, the characters have discovered ways to move on, and happily the artists involved in the production do, too. In the spirit of the city in which the play is set, a fourpiece Dixieland band – guest musicians Joe Klaus, Ed Kliman, Lindsey Verrill, and Joe Woullard, making you wish they'd been laying down those beats all through the show – strike up a jubilant tune of celebration while Philip Smith, as Katrina's Big Daddy, literally hammers out a rhythm of rebirth and Keisha Wright, beaming as Katrina, declares confidently that New Orleans will be rebuilt. The musicians lead the cast in a line out of the theatre, and we follow them out, filled with a sense of life's resilience and buoyed on notes of hope.