The Water Principle

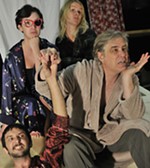

Director Ken Webster's production of 'The Water Principle' seems as much at cross-purposes with the quirky, strange script as its characters are with one another

Reviewed by Barry Pineo, Fri., June 24, 2005

The Water Principle

Hyde Park Theatre, through July 2

Running Time: 1 hr, 55 min

Addie's food supply is limited. It consists of worms, scrawny birds, and beans. Her only neighbor, Weed, has all of the beans. Canned beans. Weed uses the tinned legumes as bargaining chips to try and make Addie sign over the rights to her land so he can build an amusement park that he's going to call Weed's Wonderland. He's a man of action, he says, and he says he's got backers and backhoes at the ready, although neither ever materializes. The only thing that does materialize is Skimmer. Skimmer is a walker. When he runs out of food, he walks until he finds a place where there is food. He happens upon Addie's shack one day and manages to wheedle his way inside. He, like Weed, wants something from Addie. At first it's food, but eventually it's Addie. He wants Addie to walk with him, but she can't. She has responsibilities. Addie believes a great stream of water, an underground river, flows beneath her home. That's the reason she'd rather eat worms than sign her land over to Weed for a few cans of beans. She's there to protect the water.

This is the bleak world of Eliza Anderson's The Water Principle, and like so many of the plays produced at Hyde Park Theatre, this one is quirky and strange, with characters who work at cross-purposes with one another, often to great comic effect. It's a formula that has worked well in many instances for Hyde Park Artistic Director Ken Webster, who directs here and takes on the role of Weed, but this time it doesn't. Often, the characters don't seem to connect, either to themselves or with one another. Katherine Catmull's Addie, with her loud, panicked voice, big wide eyes, and darting expressions, appears to be more than slightly insane, and yet she has by far the most sane dialogue in the play. Webster's Weed says he's a man of action, and he talks like one, always in control, consistently using the same sing-songy, commanding voice, and yet it's clear from everything he says and does that Weed is whacked out. (An amusement park? Who, exactly, is going to be amused?) Joey Hood offers the most convincing performance as Skimmer; he doesn't seem to be putting anything on, seems to trust that the text will carry him, and to a great extent it does. Add Paul Davis' set design, which has an effective rake but otherwise flattens out the stage picture; Robert S. Fisher's ominous, oppressive sound design that has barely a hint of the humor in Anderson's play; and so many moments where characters aren't looking at one another, even when their very lives are being threatened, and it adds up to a perplexing evening.

Of course, it may be that I just didn't get it. Playing against the apparent desires of a playwright can, on occasion, be considered a legitimate choice, but any playwright's intent should first and foremost be considered a potent force and, like the life-giving water flowing under Addie's shack, be respected, preserved, and protected.