Body and Soul

The Subterranean Theatre Company production of John Mighton's Body and Soul is provocative and features a talented cast, but it never lets us get to know the play's characters.

Reviewed by Barry Pineo, Fri., Oct. 13, 2000

Body and Soul: At Arm's Length

Hyde Park Theatre

Through October 28

Jane works in a funeral home preparing corpses for burial. She's much more interested in the dead than the living. In fact, as she's busy working on a young corpse, she barely ever looks at Mark, who is desperately searching for a way to ask her out. She eventually puts him off, and after he leaves, she begins making out with the dead man.

Sally is married to Henry. Henry, like Mark, is searching desperately for a connection -- he just doesn't know with whom, or even what. Sally thinks that she should be enough; she is, after all, an attractive and intelligent human being. Mark, however, seems much more interested in something nonphysical. He's reading a book on Buddhism, and he eventually decides to volunteer for an experiment involving virtual sex.

As you can infer from the above, John Mighton's play is more than a bit out of the ordinary. Or is it? While necrophilia and virtual sex are not exactly everyday subjects, Mighton uses these as jumping-off points to address much larger questions: What constitutes a loving relationship? Is emotional connection or physical connection most important? Can you, or should you, have one without the other? Or do we really need any kind of connection at all? Do we really need each other, or do we just need another body, real or not?

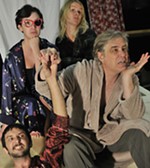

The play is provocative, and (also typical for a Subterranean Theatre Company production) the cast is a talented one. Katherine Catmull as Jane, Eric Peterson as Henry, and Jenni Rall as Sally bring plenty to the table as performers. In multiple roles, Corey Gagne, with his slightly manic enthusiasm, often steals the scene right out from under everyone. Shannon Grounds, as a virtual reality scientist, turns in an effective scene selling her own brand of futurism.

Director Ken Webster keeps things simple and stark. Marco Noyola's set design consists of an empty stage strung with taut, thin, white rope and necessary set-pieces -- tables, chairs, and the like -- which are struck and reset during blackouts between the scenes. Webster designed the costumes, which initially consist of black and white, then move to slightly more colorful but still unobtrusive pieces (although I could have done without Henry's omnipresent T-shirt). Webster's sound design matches the emotional quality of the scenes, a synthesized feedback underscoring the more bizarre passages and a mournful, bluesy piano accentuating others. During scenes, the actors barely move. For the most part, they either stand or sit in place and simply talk. At the same time, during more than a few scenes, the characters almost never make eye contact with each other. I assume this is purposeful -- that the play, being in a sense about connection, was staged in a physical way that mirrored its themes. Along with this stillness and sense of disconnection, Webster keeps the tempo quick. Pauses and silences aren't much in evidence, except at the beginnings and endings of scenes.

While what I saw made sense, the playwright doesn't give us much to go on. We only rarely learn something concrete about the characters -- where they live, what kind of work they do, what their families are like -- so what we're left with is what the characters do. And because they don't do much in a physical sense -- and they do everything so quickly -- we never really get to know them. The play is a long one-act, but at less than 60 minutes, scenes could have been played more fully without hurting the production. Despite their strangeness, I wanted to get to know these people better. It was disappointing that I wasn't allowed to.