Lost World, Found Footage

The radical art of Bruce Conner

By Josh Rosenblatt, Fri., Oct. 31, 2008

The history of filmmaking, like the history of everything else, is written by rebellious souls. From the early special-effect experimentation of Georges Méliès to the revolution in Soviet montage spearheaded by Sergei Eisenstein, from the post-expressionist visual revelations of Orson Welles to the handheld brashness of Jean-Luc Godard, from the visual meditations of Terrence Malick to the temporal high-wire act of Alejandro González Iñárritu and Guillermo Arriaga, it's always been those way out on limbs who have wiped away barriers and expanded the definition of what film is capable of.

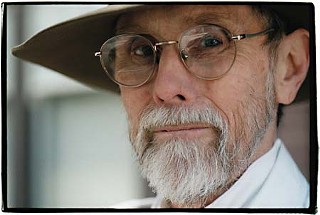

Most of the time, of course, the filmmakers with the most rabid and insatiable devotion to artistic exploration are the ones least heard of, outliers from the visual art world, avant-gardists who have more in common with Mark Rothko or Damien Hirst than Arthur Penn or Wes Anderson. I'm thinking of Stan Brakhage, Maya Deren, Ken Jacobs, Peter Whitehead. I'm thinking of directors more interested in theory than in story, who will never see their faces on the cover of Premiere because they're indifferent, even hostile, to the whims of the marketplace. Such a rebel was Bruce Conner, the protean painter, collagist, and sculptor who died this past July and whose work as an internationally renowned yet highly controversial movie director is being honored by the Austin Film Society with a one-night retrospective this Wednesday at the Alamo Drafthouse at the Ritz.

Restless, subversive, and infused with a deep sense of political and social indignation, Conner was already an artist with a reputation when he decided to try his hand at filmmaking in 1958. Building on the ideas he had developed as a sculptor of assemblage pieces (work built out of construction materials, pieces of furniture, photographs, women's nylons, and other found objects), Conner created a new approach to the art of filmmaking using found footage – old newsreels, instructional films, test patterns, whatever he could get his hands on – and radical editing techniques. The result, the revolutionary "A Movie," is an ironic and acerbic condemnation of American violence that turns commonplace images and sounds of American triumphalism back on themselves.

Which is what Conner was all about: getting viewers to look at the world they knew, the world they felt comfortable with, in a new way. Just as he did with those stumbled-upon seat cushions and family photographs, Conner edited together footage of car races, military tank raids, car crashes, sinking ships, surfers, pinup girls, cowboys, and air bombers in order to juxtapose, and therefore recontextualize, artifacts from our collective memory in the hope of discovering new meaning in them and forcing his viewers to reconsider creaky symbols of American power and exceptionalism. In Conner's art, nothing should be taken for granted: If things aren't constantly being questioned and taken apart, then we aren't doing our jobs as conscious human beings.

Which isn't to say that Conner was a pedant or a bore. On the contrary, his films are often emotional and aesthetic revelations, containing moments of real joy and sorrow. Plus, the man was a born avant-gardist, a child of abstraction, so for his movies to be populated by easily identifiable one-to-one metaphors would have robbed them of their power to confound and enlighten. One can only guess at the reasons why Conner found such fertile source material in medical, educational, and government films, and God only knows the meaning behind the repeated sequences of scurrying dots that make up 1981's "Mea Culpa." Are those dots stand-ins for harried humanity? Are they symbols of a collapsing universe? Or are they just moving dots? The answer, of course, is all of the above and none of the above. Or a few of the above, depending on your mood.

For Conner, the important thing was not that answers were found but that questions were asked. Nothing worried him more than the stultifying familiarity that results from repeated exposure to clean, simple, inherited solutions to complex problems. For example, in his disjointed 1967 meditation on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, "Report," Conner takes footage from the famous Zapruder film and blends it with scenes from a bullfight to call into question accepted notions not only of what happened on that fateful day in Dallas but also of the resulting deification of Kennedy and his wife, notions that may make us feel safer, more comfortable, but that also dull and eventually destroy our ability to truly see the world in all its ambiguity.

And that, I think, is the ultimate compliment one could pay a late filmmaker on the occasion of his retrospective: He tried to help the world see itself more clearly.

Austin Film Society presents Avant Cinema 2.3: In Honor of Conner on Wednesday, Nov. 5, at 7:55pm at the Alamo Drafthouse at the Ritz. Filmmaker Michelle Silva, representative of the Bruce Conner estate, will be in attendance for a Q&A. For more info, see www.austinfilm.org.