Art, Stunt, or Punk?

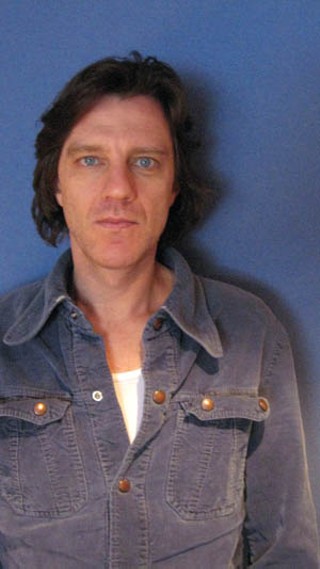

James Marsh on his dizzying documentary 'Man on Wire'

By Josh Rosenblatt, Fri., Aug. 8, 2008

Early on the morning of Aug. 7, 1974, a young French street performer named Philippe Petit stepped out into the void between the two towers of the World Trade Center and stood suspended in air, 1,368 feet above the concrete of Lower Manhattan. For nearly an hour, Petit strolled back and forth along a wire he had specially designed and illegally rigged for the occasion, spinning here and there, even dipping and twirling like a dancer. Then he quietly strolled back to the roof of one of the buildings and into the arms of the police ... then into jail and then into psychological evaluation and, finally, into New York legend.

This week, British writer/director James Marsh (The King, The Team) releases his Man on Wire, a thrilling documentary about the events of that fateful morning as told by those who were there, including the irrepressible Petit himself and his team of faithful theoreticians, designers, co-conspirators, and fellow dreamers who helped him plan what can only be called the greatest artistic heist in history. Split between interviews and sepia-tinged re-enactments of the illegal deed, Marsh's film is full of art, intrigue, conspiracy, audacity, high crime, and low comedy.

In other words, everything Philippe Petit could have hoped for.

Austin Chronicle: Why did you make this movie? What about Petit's story spoke to you?

James Marsh: I first thought about making the movie after reading Petit's book, To Reach the Clouds, which is a very personal, very subjective memoir. And my first reaction to it was, "It's like the script for a heist film." There are so many criminal elements involved in the execution of the plan, from breaking into the towers to the recruiting of an inside man to the rigging of the wire. So while I was reading this gripping crime narrative, I thought it would be fascinating to create a documentary through what is essentially a heist-movie structure. And because you know the outcome – you know Petit is alive and that he succeeded – and because the journey to get to this objective is so preposterous and so unbelievable – there's so much that could have gone wrong and did go wrong – that structure keeps things surprising and suspenseful.

AC: Was Petit as irrepressible as he seems to be while you were making the movie? If he wanted to get up and walk around the room during an interview, was he just going to get up and walk around the room? Did that bother you as a documentarian?

JM: From the beginning I respected that it was Petit's story and that I needed as much from him as he was able to give me. The first thing we did was get him telling the story on camera. But this is Petit, so what started as a formal interview quickly broke down into anarchy. But why would I stop someone from telling a story that way if that's how he wants to tell it? He relived the story on film: He hid under blankets and climbed the walls and ran around the room. It's an unusual way of constructing a documentary, but it gives the movie its energy. And if you're wondering what kind of person is able to walk between the two towers of the World Trade Center ... there you have it, here he is, this is what he's like.

I tried not to get into his psychology or his motivations or what in his childhood makes him act the way he acts. I'm just not interested in that as a filmmaker. I wanted to focus entirely on the action and the choices made.

AC: In general, when you're making a documentary, are you uninterested in interpreting events and psychology?

JM: My job is to tell a story properly and to make it exciting and capture the spirit of it; I leave the interpretation up to the viewer. I find that's the problem with a lot of documentaries: There's too much interpretation and speculation and psychology. I'd much rather tell a story and see people doing things, seeing the choices they make. In that respect, Man on Wire is more like a fictional film, where character is action, and choices tell you what someone is like, as opposed to listening to a psychiatrist figure out why people are doing what they do. You see it often in PBS or A&E documentaries, where they get out the baby photograph and try to figure out the childhood traumas that explain someone's motivations. But that doesn't work for me, either as a viewer of films or as a maker of films.

Man on Wire opens locally on Friday, Aug. 8. See Film Listings, for review.