Papa Brasilia

Nelson Pereira dos Santos Retrospective

By Josh Rosenblatt, Fri., April 11, 2008

It's always a dicey proposition, mixing film and politics – a tightrope act, a thin wire separating filmmakers and their stories from sentimentality and liberal romanticism on the one hand and heavy-handed lecturing and condescension on the other. And then there's the problem of getting filmgoers, after a long week's work, to fork over 2 or 3 or 8 or 10 dollars to sit back and watch directors pick scabs for two hours on a Saturday night. Just ask anyone who's made a movie about the Iraq war how difficult that can be.

The Italian neorealists found a solution to this problem in the middle part of last century. Tired of an empty, escapist national cinema they felt didn't reflect the realities of their world, that small group set out to explore the predicament of the working poor struggling with the social and economic ramifications of a suddenly emasculated Italy after World War II. Through the use of a host of revolutionary filming techniques – including location shooting, the use of nonactors, and the dubbing of dialogue – directors such as Rossellini, De Sica, and Visconti were able to build a cinema that was political in its intent and its methods but not necessarily in its message; story, for them, still came first. It was a brilliant coup – subtle and clever, expanding the vocabulary of film without forgetting its original mandate to entertain.

Flash forward to the mid-1950s, when a young camera operator from São Paulo, Brazil, named Nelson Pereira dos Santos moved to Rio de Janeiro amid the social, economic, military, and political turmoil of that troubled time and enveloped himself in the life of the city's favelas, or slums. Harnessing the social energy of the time and tying it to the populist cinematic tenets of neorealism, dos Santos and a group of young filmmakers formed a collective to shoot a script he'd written about the lives of the poor in a rapidly developing (and vaguely democratizing) country. The movie was called Rio 100 Degrees F. (Rio 40 Graus). With its interweaving storylines mapping the lives of the poor over one extremely hot day in Rio, its use of location shoots and amateur actors, its focus on issues of poverty and social disenfranchisement, and its tone of first-person immediacy, the film revolutionized Brazilian cinema by liberating it from its glamorized Hollywood roots and turning it into a tool of social dissension, all the while expanding the goals of neorealism to include outright political enthusiasm and partisanship. With it, the Cinema de Novo ("New Cinema") was born, and Brazilian directors had suddenly forced their way onto the film world's radar.

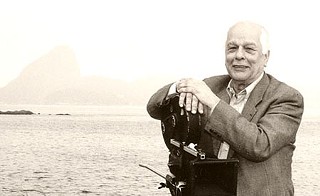

Cine las Americas pays tribute to dos Santos, the "Father of New Brazilian Cinema," with an eight-film retrospective, from the revolution of Rio 100 Degrees F. to 1963's Cannes Film Festival prize-winning Barren Lives (Vidas Secas) (based on Graciliano Ramos' novel about poverty-stricken migrant farmers in the country's harsh northeast region), from 1977's carnivalesque celebration of miscegenation in Bahia, Tent of Miracles (Tenda Dos Milagres), to his 1994 fantasia, The Third Bank of the River (A Terceira Margem do Rio). Over his 50-year career (which is still going, by the way; rumor has it the old master is locked in a room somewhere, working on his newest script – at the age of 80), dos Santos has pushed the boundaries of a whole world of film styles, from the first-person experimentations of the French New Wave to the chaotic anti-colonial films of the 1970s and on to the outright absurd voodoo rambunctiousness of the Eighties and Nineties. In return, his films, with their balance between the personal and the political and their unapologetically explosive visual language, have been the inspiration for some of the most vital and confrontational filmmakers of the last 40 years, from Italian Gillo Pontecorvo (The Battle of Algiers) to Brazilain Fernando Meirelles (City of God), whose debt to dos Santos, both in style and subject matter, is overwhelming.

"Filming was a way of participating," dos Santos once wrote. "My intention, when I began filming, was to participate [in the world], through culture and through politics. Cultural and political participation means making films alongside and with people; not to teach, but to learn with them. ... My intention was not to abandon a political point of view. Quite the contrary. It was my intention to impregnate a cultural activity with political insight." With today's directors drifting further and further away from the briar patch of political filmmaking, the time is ripe for a look back at dos Santos.

See www.cinelasamericas.org for schedule.