Bohemian Rhapsody

'Moulin Rouge' Director Baz Luhrmann Loves Love

By Kimberley Jones, Fri., June 1, 2001

The love affair with Baz Luhrmann began almost 10 years ago, when I worked at a sleepy mom-and-pop video store in North Carolina. One day I stuck a tape of his directorial debut, Strictly Ballroom, in the VCR; I think I liked the flashy blue box. And flashy certainly is the word for the Australian film, for all of Baz Luhrmann's films: flashy, but without the sour-candy taste "flashy" usually leaves. It's flash with heart, audacity plus passion. Same with William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet, Luhrmann's brilliant, boisterous 1996 retelling (no theatrical tights, just Hawaiian print shirts and 9mm "daggers") of the most famous love story ever.

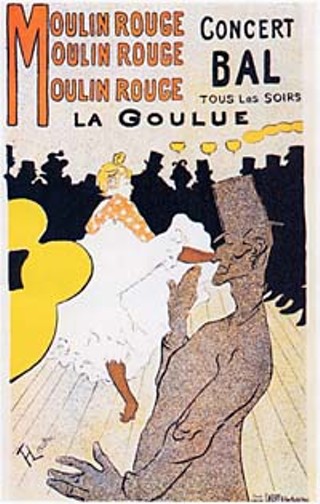

Baz Luhrmann loves love, and you can tell in his new movie, Moulin Rouge. The film, opening in Austin this Friday, June 1, visits the 19th-century Parisian nightclub where painted-face courtesans high-kicked the can-can and aristocrats and bohemians found they had a few loves in common (absinthe, the lovely-legged ladies of the Moulin Rouge). The film is loud and exuberant, just like Luhrmann's first two, but, also like his first two, in every frame of every scene beats a heart. A loud, exuberant heart, yes, a flashy heart, but a heart that's practically bursting to believe in -- "above all things" -- love.

Moulin Rouge is a simple story, really, a love story between Christian (Ewan McGregor), a penniless poet, and Satine, the "Sparkling Diamond" of the Moulin Rouge (Nicole Kidman, somehow channeling fire and ice simultaneously). And yes, the thing that everyone's talking about, what has critics dividing up into two warring camps, is Luhrmann's use of anachronistic music. The film draws from pop-music legends -- Elton John, Dolly Parton, U2, even Nirvana -- to tell this turn-of-the-19th-century tale. Can it be jarring to see tuxedoed men chant "Smells Like Teen Spirit" ("Here we are now, entertain us") in 1899 Montmartre? To watch characters in period garb tango to the Police or declare their love to the strains of the most clichéd songs in pop history? Yes. Can it be absolutely, disarmingly lovely too? Very much so.

Baz Luhrmann takes chances with Moulin Rouge. Some of them work, and some of them don't. But whatever artistic risks Baz Luhrmann takes, he does it with heart. Above all, he does it with heart.

The Austin Chronicle: Moulin Rouge opened last week in New York and L.A., at only two screens in each town, and sold out every performance. How great does that feel?

Baz Luhrmann: I feel good about that. But the thing that I'm incredibly happy about is that, well, I set out to make what I call "audience participation cinema." During each screening, the audience applauded to the numbers throughout the screening, at every screening. It wasn't like they didn't at 10 in the morning and only did at 7 at night. I've seen that at every screening. And what that tells me is that the notion of audience participation is working. It's about wanting to participate with other people in the actual motion picture, and that's the kind of thing we had hoped would happen. And I'm really excited about that, y'know?

AC: Pretty much everyone involved with Moulin Rouge has said it was the best filmmaking experience they'd ever had. How was the experience from the director's chair?

BL: The most difficult. And the most fulfilling. We were tested in every possible way. Y'know, I work in a very particular way; the actors have to come down to Australia, we all work at the house of Iona [Luhrmann's home in Australia]. It takes a long time. We had so many difficulties in making the film, just on a practical level. But it's fulfilling, because there's so much passion and belief in what we do, we all throw in, and I like to create an environment where the actors can take the most risk and feel the safest, while I try to keep the fear away from them.

AC: Did you set out to make a musical from the start?

BL: I've always wanted to see musical cinema work again. It's a projection, really, of the kind of cinema I've been making for the last few years. Strictly Ballroom and Romeo + Juliet are audience participation motion pictures. They're about a recognizable story in a heightened world, they're about having some kind of device, whether it's iambic pentameter or, in this case, music. Then it was about the process of constructing that, which began with identifying the story shape, because you have to have a story that is very simple, and that you know how it's going to end. So I started with the Orpheus myth. I always thought probably it would be 1899, Montmartre, because that [time and place] are a great reflection of where we are. It was a time of incredible technological change. There was extreme conservatism but also an embracing of the new popular culture that was going to end up in the 20th century. It became a great reflective palette, if you like, for where we are today. It's not a social examination of the time, but it is capturing a feeling of a time, when the world is changing. And obviously I have a lot of understanding about the history of bohemianism, having done La Bohème. [Luhrmann staged the Puccini opera in the Nineties.] I'd spent a lot of time in Paris researching bohemianism. So it's something I understood quite strongly. And then I can remember, just as a final note, going to the Moulin Rouge 10 years ago to see LaToya Jackson wrestle a snake. I didn't actually get to see it, but you don't forget a moment like that.

AC: La Bohème clearly influenced you and the story of Moulin Rouge.

BL: Sure, quite directly. We are clearly quoting and utilizing classic 19th-century tragic form.

AC: Did you first conceive Moulin Rouge while you were directing La Bohème?

BL: Mmm, in a way. Yes and no. I did want to do a postmodern La Bohème, that is true. But it was about wanting to make a musical, to look at where we are now, deal with this idea of bohemianism, and essentially make a backstage musical. So all those things came together. There were times when we looked at a quest myth, for example, and that was inappropriate, because that doesn't deal with this idea which the Orphean structure does, of a young idealistic man going into the underworld and coming to that point in his life where he realizes that you can't control everything -- people die, some relationships can't be -- and you can either be crushed by that, or you can lose the outward gifts of youth but grow spiritually inside. Without overcomplicating what is essentially a simple musical work, that is the underlying gesture of the work.

AC: You decided to use pop songs -- Elton John, the Police, David Bowie, etc. -- instead of an original score here. Did you approach the artists personally?

BL: I went and saw everybody, and some of them are old friends, and some of them I'd have to meet. Elton has always been a great supporter of mine, and he was over the moon about it.

AC: Did you experience any resistance? Were they all just flabbergasted?

BL: Ninety percent of them were so enthusiastic. Because, for them, if it were the 1940s, they'd be writing musicals. I tell you who was great -- I call her the Dalai Lama of L.A. -- Dolly Parton was so beautiful. She says: [Luhrmann mangles a Tennessee cornpone accent] "I've been really lucky with that song ["I Will Always Love You"]. It's been a hit three times now, it might be a hit again." The only person who said no was Cat Stevens, and that was on religious grounds. And I really respected that.

AC: These songs are all part of our pop music canon and, to a certain extent, have become clichés. Did you worry that the audience would be put off by the familiar music presented in a different context?

BL: That's classical musical form. That's an extremely old idea in musicals. Let's deal with the contemporary notion of it: Judy Garland sings "Clang, clang, clang went the trolley" in Meet Me in St. Louis. The film is set in 1900; she is singing music from 1940. So we're using contemporary music to get inside the characters, to make an emotional connection with characters in another time and another place. The other fundamental rule of the great period of musicals, and indeed opera, is that the audience had some kind of relationship to the music before they get to the theatre. They're actually having a relationship with music they know, and that is an important element in it. So with what you call musical cliché, you celebrate the cliché. It's like a football match. We all know the rules, but we enjoy how it plays out.

AC: I wonder how much resonance the music would have with the audience if they'd never heard it before, if they went in cold.

BL: It wouldn't play. It could play if we had some mechanism out there for getting that music to our audience so that by the time the audience got there ... Well, d'you know, that's what they did with Jesus Christ Superstar. They made the album first, almost a year before the show opened.

AC: I have to admit, sometimes the contemporary music really distanced me from the work. It was such a shock that it took me out of the story.

BL: Maybe some of it just doesn't work, or it doesn't work for you. I would say, finally, with a piece like this, because it's not naturalism, it's only between the film and the individual. It's not gonna work for everyone. The question is, if you accept the contract, do you analyze it? It's harder to participate in a participation piece if you're in fact also doing a breakdown of a new form. Now that's not a criticism [of criticism], it's just an unfortunate reality of having to go through the sort of critical process of it.

AC: I saw Strictly Ballroom and Romeo + Juliet before I was a film critic, and I watched them over and over again -- I was completely immersed in their realities. I wonder how much being a critic has shaped my impression of this film and my ability to just say "screw it," and dive in.

BL: Imagine what it's like for me. I go to movies and, unless I've had quite a few drinks and I'm really in a fun mode, it's so hard for me to actually let myself be in it. I remember when I was a kid -- this is a ridiculous story, but -- I used to collect tropical fish and breed them, and I loved them. And I'd look in the tank, and it was just a beautiful world to me. And then my father, he's very, y'know, "you must take things to the nth degree," so I started to breed and sell them and became very, very successful. I was a very successful tropical fish seller, but I lost my love of it. I lost the magic of it. Because it became about "Am I breeding the best fish?" All I'm saying is, I sympathize with that. Honestly, I'm not going to defend people who are critical of Moulin Rouge and say it doesn't work. They don't get it. But it's very hard in a participatory piece.

AC: It seems it comes down to an analytical versus emotional response.

BL: [Either you worry about] "Does it work or not?" or you go on a Saturday night after dinner with friends and experience it. I think that was the spirit in which it was made. And, by the way, your questions are absolutely legitimate. We could have fun talking about individual merits and nonesuch. I mean there are [experimental] pieces that I really like. And pieces that I think are less successful, and there are bits where I go, "Ughh, skating on thin ice."

Ultimately, I don't know whether, when we open on 2,000 screens, whether half the U.S. is going to go traipsing off to the theatre or not. It would seem a lot of people think that is very unlikely, and possibly they're right. But on the other hand, I'm buoyed by the fact that at 10 in the morning in New York City, we're packing in the theatres and a whole lot of people are applauding the musical numbers. That's a good thing to me, 'cause [it] feels like people need that experience. Therefore we've done something worthwhile. ![]()

See Marc Savlov's review in Film Listings, p.78.

William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet will play at Dobie Theatre at midnight, Fri-Thurs, June 1-7.

Strictly Ballroom will screen at midnight, June 8-14.