Working Girls

Austin Film Society's Free Series Highlights Women Directors of the Seventies and Eighties

By Marjorie Baumgarten, Fri., May 18, 2001

So what is it that we're supposed to find when we group women film directors together as a category for investigation? Are we looking for a unifying aesthetic or a commonality of experience expressed on the screen? If we're looking for signs of female nurturing, rebellion, or whatever, it's likely that we can find -- or shape -- evidence to fit our formulas. And even if we do identify certain tendencies, can it be fair to generalize across an entire sex? Is this not only unfair to women and men, whose multiplicity of traits and perspectives are the keys to their artistic visions, but also unfair to the works they create? On the surface, directors like A-Listed Penny Marshall and experimentalist Yvonne Rainer seem to have as little in common as artists Georgia O'Keeffe and Yoko Ono or authors Gertrude Stein and Agatha Christie.

The new series programmed by the Austin Film Society offers eight films to provoke inquiry and conversation. "Dance, Girl, Dance: Women Directors of the 70s and 80s" is a thoughtfully planned presentation of works by eight American women filmmakers. Excluded from this survey are widely seen hits from the period, like Amy Heckerling's Fast Times at Ridgemont High or Martha Coolidge's Valley Girl, in favor of rarely seen films that have all but vanished from the public consciousness. The films covered in the series are all works by inherently feminist filmmakers, and the chronological order of the series tracks the growth of American feminist thought during these two decades.

In order to find a lively history of women's involvement in filmmaking we have to look outside the Hollywood studio system. It is to the areas of independent filmmaking and the exploitation market during the postwar years through the early Seventies that we find the true antecedents to today's women filmmakers. Certainly, the mother of the independent film movement and champion of personal expression is Maya Deren, whose 1943 film Meshes of the Afternoon is a cornerstone work in any study of women independents. Many other women take up cameras during the Fifties and Sixties as film equipment becomes more portable and accessible to the public and film evolves as a medium of artistic expression -- among them such women as Shirley Clarke, Gunvor Nelson, and Marie Mencken, whose work also mirrors the consciousness-raising of American feminism during the Fifties and Sixties. More and more, women begin looking through the camera lens, and what they see helps bust open the "feminine mystique." In this series, the films Wanda by Barbara Loden (which has already screened) and Legacy by Karen Arthur emerged from this tradition.

During the Fifties, actress-turned-producer Ida Lupino set the stage for independent filmmaking within the Hollywood framework when she formed her own production company and directed and maintained creative control of her company's movies, which tackled such taboo subjects as rape, abortion, and bigamy. It was examples such as hers that paved the way for the exploitation houses of the Sixties and Seventies, with Samuel Z. Arkoff's American Pictures International, Roger Corman's New World Pictures, and the blaxploitation film movement leading the charge into new kinds of quick, low-budget filmmaking formulas that exploited topical issues, violence, and partial nudity to sell their movies. As long as certain narrative prerequisites were met, directors were generally allowed great freedom to make the movies they wanted to make. This resulted in idiosyncratic film identifiable by the individual touch of their directors and provided the milieu in which a number of now-top-name filmmakers got their start. Two films in this series, Terminal Island by Stephanie Rothman and Humanoids From the Deep by Barbara Peeters, are representative of this lineage.

Sometimes, although a film may have been made with conventional studio funding and conform to generic standards, the path to distribution is still difficult. Both Elaine May's Mikey & Nicky, a character study about two small-time gangsters starring John Cassavetes and Peter Falk, and Joan Micklin Silver's Chilly Scenes of Winter, adapted from an Ann Beattie novel, were riddled with studio interference during the post-production phase.

Born in Flames by Lizzie Borden is a low-budget independent film made in 16mm that successfully combines an arthouse aesthetic with a futuristic storyline. The most out-and-out feminist film in this series, Born in Flames is fashioned as a politically radical statement that also has roots in science-fiction. It also helped pave the way for independent feminist filmmakers to work totally apart from the studio system. This New York indie features Kathyrn Bigelow in a small role. Bigelow, who has gone on to become one of this country's top action filmmakers, began her directing career with the vampire film Near Dark, the final movie in this series. She has been in demand by the studios ever since.

One more thing to take into account is that these films were all made by American women. For better or worse, each of them shares a commonality of national background that may make their work different from that of female directors from other continents or political persuasions. All have also had to grapple with the givens of the Hollywood movie industry -- its production system, genre conventions, apprenticeship traditions, and so on. These films represent a period during which the wave of modern feminism was to find full flower in the United States, and these works certainly reflect that momentum. In the mechanics of their making and the subjectivity of their female characters, these films illustrate some of the ways in which women have shaped the already existing structures to satisfy their goals. Each of these filmmakers challenged conventional expectations and managed somehow to come into being in the first place. Two out of eight of these directors made films with similar titles: The Working Girls by Stephanie Rothman and Working Girls by Lizzie Borden. That, in the end, may be the most telling commonality of all.

"Dance, Girl, Dance: Women Directors of the 70s and 80s" began May 15 with Barbara Loden's Wanda and continues every Tuesday through July 3 at 7pm at the Alamo Drafthouse, 409 Colorado. Admission is free.

May 22

Terminal Island (1973)D: Stephanie Rothman; Scr: Jim Barnett, Stephanie Rothman, Charles S. Swartz; with Don Marshall, Phyllis Davis, Ena Hartman, Marta Kristen, Barbara Leigh, Tom Selleck, Roger E. Mosley, Clyde Ventura. (R, 88 min.)

"Welcome to Terminal Island, baby." This Seventies exploitation gem has been repackaged a few times since its original release, attempting to cash in on the success of its Magnum P.I. stars Tom Selleck and Roger Mosley (who have always seemed a bit embarrassed by the association -- they needn't be). Back then, they were simply a couple more undistinguished B actors in this island community of B players. By the time Rothman directed Terminal Island for Dimension Pictures, a company she formed with her husband and creative partner Charles S. Swartz, she was an experienced hand at the exploitation gambit, having made a number of movies for Roger Corman at AIP and New World. Films such as It's a Bikini World, The Student Nurses, and The Velvet Vampire established her proficiency with the nuts and bolts of the exploitation formulas while also exhibiting a noticeably feminist bent. Her female characters were always nonpassive independent sorts, the equals of their male counterparts with their own points of view, problem-solving protagonists prone to unconventional, if not utopian, resolutions. Abortion, voyeuristic lesbian vampires, rape, political activism -- all are addressed in these films. And perhaps as her signature statement, Rothman was always sure to include equalizing images of male nudity to go along with all the soft-core female nudity her formulaic plots required. "I have a specific policy when I make films to show naked men whenever I show naked women," she has said. "To have a dressed person with a nude one is to tell you immediately who is the vulnerable one. When both people are nude, I don't think there's that kind of objectification ... I want to establish a precedent which may be more humane for both." Terminal Island is a still-topical drama about a fictional penal colony established by the state of California from which there is no escape and, hence, no need for guards. There are some 40 men on the island and four women, who are forced into becoming the men's chattel. They service the men sexually and also pull their work ploughs. Divisions of sex transcend divisions of race here. A renegade group of convicts (including Selleck as a mercy-killing doctor sentenced to life on Terminal Island) breaks apart from the main group, and the women cast their lot with the renegades and also devise some of the group's savviest weapons. Ultimately, Terminal Island becomes the unlikely home of a new utopian society.

May 29

Legacy (1975)D: Karen Arthur; Scr: Joan Hotchkis; with Hotchkis, George McDaniel, Sean Allan, Dixie Lee. (R, 88 min.)

Legacy is the first feature film made by Karen Arthur, a director who subsequently worked primarily in television, directing series such as Cagney & Lacey and Remington Steele before developing into one of the most in-demand directors of TV movies. Legacy is probably Arthur's least polished work, an outgrowth of a one-woman show developed by its scriptwriter and star Joan Hotchkis. Its theatrical roots are evident, although the intensity of its sexually defined psychological experience can also be seen in such Arthur films as The Mafu Cage and Lady Beware and a sampling of her television movies, which include A Bunny's Tale, The Rape of Richard Beck, and True Women. Legacy is a witty portrait of an upper-middle-class woman's slow disintegration into madness. Hotchkis, who spent four years writing the screenplay and perfecting the role of Elizabeth, has a precision that is matched by Arthur's directorial style, which displays a unique talent for uncovering the hallucinatory nature of reality. Following a visit to her mother, the rest of the film unfolds within the spacious confines of Elizabeth's home, where she is alone and isolated but for the telephone. Ostensibly, the action centers on her preparations for a large dinner party that she is hosting. Her preparations, however, lead her down a path of memories, flashbacks, fantasies, hallucinations, and reflections on body image. The lines between reality and unreality are skillfully perforated, and our ability to distinguish between the two becomes as blurred as Elizabeth's sensations. Gradually, we become suspicious of all presentations of reality. Made around the same time as A Woman Under the Influence, Legacy explores realms of madness never even approached by the John Cassavetes/Gena Rowlands collaboration. Woman explored society's reactions to a woman behaving oddly and, ultimately, unacceptably. Legacy focuses on one woman's reactions to herself and her cultural heritage.

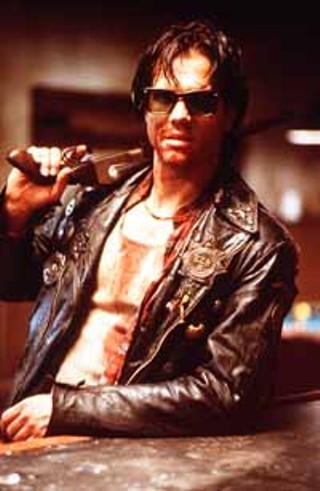

director Elaine May

June 5

Mikey & Nicky (1976)D: Elaine May; Scr: Elaine May; with Peter Falk, John Cassavetes, Ned Beatty, Rose Arrick, Carol Grace, William Hickey, Sanford Meisner, Joyce Van Patten, M. Emmet Walsh. (R, 106 min.)

Before becoming involved in filmmaking as an actress, scriptwriter, and director, Elaine May made a name for herself as one-half of the successful comedy duo Mike Nichols & Elaine May. The sharp, sardonic comedy of her stand-up act has not always translated well to the screen, however. Although she was nominated for an Oscar for co-writing Heaven Can Wait with Warren Beatty, her film career is usually remembered for the financial debacle of Ishtar. Mikey & Nicky is often, and unfairly, categorized as a John Cassavetes knockoff, which diminishes the originality of May's screenplay and this character study she crafted especially for co-stars Cassavetes and Peter Falk. She unleashes the darkest, most mercurial side of Cassavetes, and in Falk finds the actor's moral ambiguity that had been obscured as a result of his then-popular run as TV's Columbo. The movie is basically a two-person drama about old friends and maybe current enemies. Nicky (Cassavetes) is a small-time hood with a contract out on his life. Mikey (Falk) is his lifelong friend who may or may not be trying to help Nicky escape his fate. Ned Beatty is the hit man who circles them rapaciously as they spend a high-wire night together. Nicky charms and chills all he encounters, and Mikey begins to recall all the small resentments that have built into a now-impregnable force. The movie grinds along its dark, mordant, and fascinating path until it culminates in one of the most emotionally harrowing scenes ever filmed. May faced difficulties editing Mikey & Nicky, spending years trying to cut together something that satisfied the studio's desires for more conventional fare without compromising her own vision. The film was re-released to critical kudos in 1984.

June 12

Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979)D: Joan Micklin Silver; Scr: Joan Micklin Silver, based on novel by Ann Beattie; with John Heard, Mary Beth Hurt, Peter Riegert, Kenneth McMillan, Gloria Grahame, Griffin Dunne. (PG, 93 min.)

Joan Micklin Silver first came to national attention in 1975 with her stirring and evocative film Hester Street, starring Carol Kane as an Orthodox Jewish woman who comes to the New World to be with her husband but finds the old ways out of place in this new American society. The independently made movie features strong performances and great period re-creations. Its story of a husband and wife who do not quite connect resonates in Chilly Scenes of Winter. Based on the novel by Ann Beattie, who has a cameo as a waitress early in the film, the movie tells the story of an obsessively heartsick man (Heard) who pines for his lost love (Hurt). Casting the man as the lovelorn character provides an interesting role reversal to the usual romantic comedy. The story of the affair is told in snippets, little flashbacks or memories that provide the story's "chilly scenes," and telltale moments. The movie is chock-full of wonderful character studies and ironically contemporary sensibilities. An added treat is the appearance of film legend Gloria Grahame. The film's self-knowing spirit and sly wit may have gotten in the way of its box-office figures. After a disappointing initial release under the title Head Over Heels, the film's upbeat ending was re-shot to better capture the tone of Beattie's novel and re-released on video as Chilly Scenes of Winter.

June 19

Humanoids From the Deep (1980)D: Barbara Peeters; Scr: Frederick James; with Doug McClure, Ann Turkel, Vic Morrow, Cindy Weintraub, Anthony Penya, Denise Galik, Linda Shayne. (R, 80 min.)

Humanoids From the Deep arrived at the tail end of the drive-in exploitation boom, and in many ways this Roger Corman release resembles his very first solo production, 1954's Monster From the Ocean Floor. Humanoids is a blend of horror and comedy, but by this point, Corman's budgets had grown enough that the mutants looked more "realistic" than the earlier homemade varieties. Still, the theme is the same -- ecological mayhem brought about by negligent scientists and depressed economic circumstances. It is a theme that seemed all the more naturalistic in post-Three Mile Island, post-Love Canal 1980. It's difficult to pinpoint a true villain in Humanoids. The scientists here are trying to alter the DNA of salmon so that they might grow bigger and faster and replenish the depleted reserves of the area and its diminished livelihood. But, of course, mechanical error causes the unfortunate release of a "bad" batch of salmon, and catastrophe ensues. The townspeople's fight to protect themselves also reveals their insidious racism, as the sole exception to the community's so-called progress is a Native American who suffers the citizenry's abuse. If the townspeople are guilty of racism, however, then the humanoids could be cited for their sexism. Men and women are subjected to different fates. Men are mauled to death since they are regarded as territorial threats. But women are the key to the future of the humanoid species and are thus raped by the monsters to perpetuate their genes. Of course, it's a great exploitation plot device to rip more bikinis off the bodies of fertile young women, and reportedly several more inter-species rape scenes were added by other directors after Peeters wrapped shooting. Still, Humanoids features a number of strong female characters, including a lead scientist and another who defends her homestead from the marauding creatures. Also of note is the listing in the credits of Gale Ann Hurd as a production assistant. After this early experience in genre filmmaking, Hurd went on to produce such action spectacles as Aliens, The Terminator, and Armageddon.

June 26

Born in Flames (1983)

D: Lizzie Borden; Scr: Lizzie Borden, Hisa Tayo; with Honey, Jeanne Satterfield, Adele Bertai, Becky Johnson, Pat Murphy, Florence Kennedy, Kathy Bigelow. (NR, 90 min.)Born in Flames is a feminist action/adventure film that is superbly crafted, politically uncompromising, and thoroughly engrossing. The setting is the future: New York City 10 years after the Social Democratic War of Liberation. Rape, day care, and sexual discrimination are still unresolved issues in this new society. With sexual oppression the norm, women in this post-revolutionary world still face the same old problems of how to create a social structure that is responsive to their needs and goals. Four separate groups of women activists reflect different ideological and tactical positions within the women's movement. The Women's Army, led by a black lesbian construction worker (Satterfield), is a racially mixed group that organizes feminist protests, labor demonstrations, and vigilante actions. Phoenix Radio is a black women's underground station with musical roots in soul, reggae, and gospel. Radio Regazza is a white women's underground station rooted in punk rock. And the Socialist Youth Review is a group of women editors and intellectuals who work within the party to establish policy on women's issues. Feminist legal maverick Flo Kennedy also has a role in the movie, much as she did in real life, as a self-styled voice of independent thought. "The film is really about a war of words," says Borden, "about how no group should be allowed to lose the right to define itself through language." She wanted to make a film that was "narrative but not narrative in any way that an audience could find escapist. I wanted the focus of the film on the media and the language." Beautifully made, courageously edited, and swift-moving, Born in Flames assumes a certain intelligence on the part of its audience. It is as much a tapestry of ideas and philosophies as it is a record of actions and characters. A challenging, provocative film, Born in Flames is a work that is both humanist and revolutionary. (June 26)

July 3

Near Dark (1987)D: Kathryn Bigelow; Scr: Eric Red, Kathryn Bigelow; with Adrian Pasdar, Jenny Wright, Lance Henriksen, Bill Paxton, Jenette Goldstein, Tim Thomerson. (R, 95 min.)

Near Dark is the third film directed by Kathryn Bigelow, although the first one to gain wide attention. It's a smart, creepy, violent, funny, and modern vampire movie that benefits from some wonderful performances, a stunning visual texture, and music by Tangerine Dream. Near Dark established Bigelow as the creator of stylish, inventive work that looked great and imbued the old formula with new life. The reviewer for Variety noted, however, that the movie's "main point of interest will be the work of Bigelow, who has undoubtedly created the most hard-edged, violent actioner ever directed by an American woman." A dubious distinction, perhaps, but one that has followed Bigelow throughout her career. She has continued to work within genre formulas and has established herself as the foremost woman director of action movies. Subsequent films include the police drama Blue Steel, starring Jamie Lee Curtis, the undercover FBI/surfer/bank robber movie Point Break with Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze, the science-fiction of Wild Palms and Strange Days, the unreleased romantic thriller The Weight of Water starring Sean Penn, Elizabeth Hurley, and Catherine McCormack, and the upcoming K-19: The Widowmaker, a reportedly $60 million submarine actioner starring Harrison Ford. Near Dark focuses on an itinerant vampire clan whose family security is upset when a newcomer enters their group. Adrian Pasdar plays an Oklahoma farmboy who gets more than he bargained for when he hassles the new girl in town for a kiss. The story, written by Bigelow and horror specialist Eric Red (Body Parts), locates the luridly erotic undertones that are intrinsic to the vampire myth and successfully obscures the comfortable lines separating normal from abnormal. Familial loyalty and love between a man and a woman are the dominant motifs that underscore all the movie's bloody mayhem. The film was also something of a homecoming that reunited three of the cast members from Aliens: Bill Paxton (in an all-out mad performance), Lance Henriksen, and Jenette Goldstein. Bigelow's picture of the darkness residing in the American heartland still resonates today.