House Arrest

APD brass decided they had a problem with Officer Jermaine Hopkins – so they assigned him to stay-at-home duty until they could figure out what to do with him. That was a really bad idea.

By Chase Hoffberger, Fri., Dec. 19, 2014

From the get-go, this wasn't a standard "drunk person's trying to drive home" call. May 18, 2013, 12:38am: Jermaine Hopkins rolled up to a scene that by then had spilled out onto the street.

Jason Roche was out there. He was drunk, and Hopkins was familiar with his history: He was a known drug user and probationer, and the Austin Police Department knew he owned a gun. Hopkins saw him opposite a younger woman – Melynda Trevino – and immediately called dispatch for backup, then questioned the couple. Trevino was only 20. Roche said she'd been "drinking with us"; Hopkins arrested him for furnishing alcohol to a minor, and public intoxication. Later, he'd arrest Trevino for intoxication, as well.

In the interim, Roche's wife, Sarah, walked out of their house and came upon the conversation happening between Trevino, Hopkins, and her husband. Hopkins suspected Sarah was drunk as well. He got stern when she began to walk away, and told her to stay put. Sarah refused; Hopkins insisted: "I could arrest you for evading." He didn't want people coming and going, he'd write later, when he knew that there might be a gun around.

Midway through the stop, while Hopkins was handling Roche's arrest, yet another woman, Vanessa Price, walked from the Roches' house and then into the street to see what was happening. She was belligerent; Hopkins asked her to stay away. After a while, she sat down – "hesitantly," Hopkins noted – after he'd asked her over and over to do so. Price took out her cell phone, and started trying to make phone calls. Hopkins didn't like that, and told her so; his requested backup hadn't arrived yet. He asked Price to put the phone down eight different times, he said, but she refused. So he walked over to arrest her.

Price resisted, which led to Hopkins performing a takedown. His backup, Sgt. Jeff Greenwalt, arrived just after Hopkins got Price into handcuffs. The first thing that Greenwalt saw was Hopkins' knee on Price's shoulder.

Response and Resistance

Months later, at an Internal Affairs review, Trevino described Price as being "emotional" and "belligerent" during the few minutes that Hopkins dealt with her. She "would not stop yelling," she said. "She was screaming. She was not happy." Greenwalt also thought her "uncooperative" after she wouldn't give her name. Even Emergency Medical Services saw it when they showed up to treat her shoulder. "Belligerent," they said. "Rude to them. ... She wouldn't cooperate fully" with any officers.

Greenwalt thought Price's arrest was acceptable, but had questions about Roche's. He passed the arrest report along to the next reviewer, Lt. Stephen Barnes ("response-to-resistance" arrests are always reviewed), and Barnes immediately took issue with Hopkins' arrest of Price. "It never should've frigging happened in the first place," he'd say later. He told Cmdr. Todd Gage and Operations Lt. Joe Robles that the two should begin an IA review, and then had the charges thrown out against Price.

"He should never have put hands on the person," Barnes said during his IA interview. "It's the kind of situation that I've run into before, and I brought it to those above me. ... We had an officer [whose] force was within policy, but we probably could have avoided ever having to do that in the first place if we would have used a different tactic or a different method. This, to me, was poorly handled."

Among the APD reviewers, there were concerns about Hopkins' tone throughout the episode – the way he'd communicated. He was also criticized for intentionally omitting information from the affidavit, and was asked why he didn't wait the five minutes it took for backup to arrive before taking decisive action. Primarily, Hopkins' chain of command took issue with his notion that Price had interfered with the arrests of Roche and Trevino. They noted that she only came within 20-30 feet of the officer, and never physically interfered with him. Even Greenwalt conceded: "She didn't get as close as I thought she was going to, based on what he told me," he testified during his IA review. Indeed, notes from Hopkins' affidavit never record Price's distance from him during the incident.

(Hopkins' pending appeals prevent APD from responding to questions about this story, although Chief Art Acevedo did say the memos "speak for themselves.")

In Nov. 2013, Acevedo handed Hopkins an eight-day suspension as a result of the incident; not for the detaining, specifically, but for the way he handled subsequent coaching, seemingly refusing to learn from the experience. "Officer Hopkins stated that he would not have handled the situation any differently," Acevedo's suspension memo said, "and that he believes the charges filed against Mrs. Price were valid." Acevedo hit him with two separate violations: Responsibility to Know and Comply, and Neglect of Duty. He added that he took "Officer Hopkins' total work and performance history" into account.

Mounting Concerns

To this day Hopkins remains convinced – adamantly so – that he shouldn't have treated Price any differently.

"I had probable cause to arrest her as soon as she stepped off the property," he explained when we met for coffee in late November. "I was actually trying to avoid doing so, because I was dealing with the situation. She entered the scene; I told her to stay back. Her friends told her to stay back as Jason is being handcuffed. So I said: 'Now you are being detained. Stay on the curb.'

"Interference doesn't have to be based [on] distance. If you're hindering me from my job – beyond just speech alone – it is interference. She came into a scene. I told her to stay back. She's drunk. The scene's escalating. If anything, my report downplayed her actions."

The 33-year-old Hopkins says he never writes anything in affidavits unless he knows for sure that he can quantify it. Debate raged over the precise distance, but Hopkins didn't bring a tape measure. It's tough to calculate nine steps for distance after 12:30am.

Hopkins is a sprightly guy – alert and cordial, with a wide, naive smile and a tendency for nervous body language when he gets talking. He joined the APD in September 2009, after a seven-year stint in the Army that included time as a military police sergeant and a one-year deployment in Iraq (during which he earned a Purple Heart). He had worked in law enforcement since he was a teenager, having begun as a cadet with the Vacaville PD in California.

In Austin, he made a positive early impression on his commanders, earning good scores on his evaluations in 2011 and 2012, the records that were available. Recommendations Hopkins provided from members of his chain of command described him as a "highly active officer" who initiated a lot of traffic stops, practiced proactive policing, and accepted training recommendations without being negative. Concerning a transfer request Hopkins made to be moved from patrol to Metro Tactics, co-workers hailed his positive attitude and willingness to accept new responsibilities. One sergeant even called him "a great asset to any team."

However, not everything was hunky-dory. Many within the APD thought that his communication skills needed an overhaul. In fact, he was sustained on a rudeness complaint from one woman (he encountered her three times, and she thought he had it in for her). Later, he was again sustained on a complaint after telling someone who wasn't cooperating to "sit down and shut up." In a 2012 Performance Improvement Plan review, he was given an "Unacceptable Performance" grading after he failed to write a report following a call about a neighbor leaving a bicycle in a sidewalk. He was reported for incidents such as driving erratically and not properly double-locking handcuffs. Co-workers reported problems; they issued complaints that questioned his abilities.

Most concerning to his supervisors was his consistent reporting of a high number of response-to-resistance incidents – that is, incidents in which the officer responds to resistance from a person during an arrest. At one point, he had 20 R2Rs (though many, he says, occurred as he was assisting other officers, and all were ultimately considered within policy). His next closest colleague had accumulated only 11.

In conjunction with those concerns, in May 2012, Hopkins was sent to meet APD staff psychologist Carol Logan for a series of psychological evaluations, though he didn't hear anything of the results until September 2013.

By May 2013, when he arrested Vanessa Price, Hopkins' troubles with APD had been mounting, and talks had already opened for Logan to complete the 2012 psychological review.

The fallout from the Price arrest meant Hopkins would go onto restricted duty. He left his South Austin patrol unit and transferred to Narcotics, only to move again – this time to Warehouse – after his denied transfer sparked his first racial discrimination complaint with the city. Unable to perform the labor the warehouse assignment required after aggravating a military injury, Hopkins was reassigned to HALO (High Activity Location Observation) to monitor surveillance videos around the city.

On Aug. 7, 2013, Hopkins filed an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint, on the same grounds. Six days after APD found out, he was assigned to what he calls his mandated "house arrest": active duty, without duties – just sitting there in his house all day, every day. Four days of 10 hours became five days of eight. He got a pager, and lost his official APD email. Any errand had to be approved by his supervisor, Ely Reyes.

Alone With a Keyboard

Hopkins was earning a base salary of $70,549.44 when he was assigned to his home in Sept. 2013, and he continued to earn that salary until his termination (in civil service terms, "indefinite suspension"), on Oct. 30, 2014. His first stint of "house arrest" took nine months and stretched beyond his first suspension, until he could be considered fully fit to return to duty. Along the way, his reputation within APD continued to deteriorate.

One day after being assigned to home duty, Hopkins filed an amendment to his initial EEOC complaint, detailing what he believed were retaliatory tactics. He filed another one month later: charging more retaliation, restricted access, obstruction from Human Resources, what he considered an "intimidating" email sent by the executive team. During that time, he also accused Ely Reyes of doctoring overtime forms, and argued about the omission of the words "air quotes" in his review statement. He says Reyes denied his request to return to family and friends in California for the holidays.

Later on during that first stint at home, in the middle of his Internal Affairs review, Hopkins discovered (through open records requests) the results of the tests conducted by Dr. Logan. They detailed concerns about his communication skills and mental stability, among others. Hopkins wrote in appeals and personal emails that he considers her report "outdated" and "in contradiction to my performance evaluations," and believes Logan "failed to maintain ethically obligated independence and objectivity."

Texas law says any firefighter or police officer believed to be incapable of fully performing his duties can be made subject to a "fitness-for-duty" examination, which measures an officer's abilities as "able" or "not able" on 115 different subtopics. Topics range from the ability to follow protocol, such as Search and Seizure etiquette, to physical capabilities and behavioral functions. Hopkins commissioned his own physician, Dr. Martin Molina, to give him the fitness examination, and he passed it last October. Soon after, he learned that Acevedo wouldn't accept Molina's findings. Acevedo ordered Hopkins to take a second test, administered by a city-appointed psychologist, Dr. Casey O'Neal, who Hopkins claims distorted his statements. He failed her test in January, eventually setting up a third consultation with a three-member board assembled by the city's Civil Service Commission.

When he wasn't being tested, Hopkins had to remain within his house during work hours, left to fill his days without any official orientation or focus. He considered the conditions hellish, noting to Sgt. David Daniels: "Surviving a year in Iraq is no longer my greatest accomplishment. APD House Arrest 2013/2014 is." He explained to me later: "The anxiety comes from sitting there not knowing what's going on with your job ... not knowing how to prepare for what's going to happen if you lose your career."

His friends couldn't believe what he was enduring. Notably, Tomi Kingi, a 17-year veteran of the Vacaville PD who had taken Hopkins on night-shift ride-alongs when he was a cadet in the late Nineties, took the time to speak with Hopkins nearly every day. "Jermaine doesn't have a wife and kids," he said. "He doesn't have a girlfriend. At least have some compassion for an officer who's sitting at home who didn't kill anybody, run somebody over, or beat somebody up." He said Hopkins "has never had any intention but to demonstrate truth and integrity his entire life. "You come in and question that integrity and character: more power to Jermaine."

To fill the time, Hopkins filed outdated overtime invoices (to recoup wages lost through the suspension), and tried to get supplemental, off-hours work at H-E-B. He emailed APD personnel constantly, as well as other city of Austin employees. He accused the city of being in "violation of sec. 552.223, Texas Government Code," which mandates no subjectivity in responding to public information requests. He discovered, and noted in a third EEOC complaint, that one of his superiors had forwarded his medical information to another sergeant, who in turn passed it along to the Office of the Police Monitor. He argued once again that he was being discriminated against by the department.

"Some of his actions that he took were outside of our recommendation," said Wayne Vincent, president of the Austin Police Association. He said Hopkins came to the union for help when he was first charged with allegations from the Price arrest. "I have email documentation in which he was asking for more assistance later on. We advised that we'd assist in any way we can, but he has just not taken our advice or recommendations, we're kind of at a loss to help him."

Left to his own devices, Hopkins started researching old cop cases – looking into the reasons why APD officers had been disciplined. He made lots more open records requests (29 between Sept. 2013 and Jan. 2014) and started piecing together the details. He noted the reports concerning the officers who arrested jogger Amanda Jo Stephen near UT in February (see "Headlines," Feb. 28), and thought Acevedo's defense of those officers' use of force was bogus.

In mid-April of this year, Hopkins was told in an email from Acevedo that he must "comply fully" with the Civil Service Commission on his fitness-for-duty test. Hopkins believed the investigation was too broad (he had objections to test questions that asked about issues outside of his specific job requirements), and wouldn't agree to it. He emailed City Manager Marc Ott – copying the mayor and one City Council member – insisting that Acevedo had issued an illegal order. He was required to disregard unlawful orders, he said, and contested Acevedo's assertion that the order was lawful.

Though he'd eventually comply with the requests made by the CSC, the exchange over unlawful orders eventually spelled his doom: It became the first chronological point of order in the 96-page indefinite suspension memorandum Acevedo would issue in October.

Enter Antonio Buehler

In late May, the CSC board ruled in favor of Hopkins: fit for unrestricted duty "without the need for accommodations." He responded by notifying Acevedo (copying Mayor Leffingwell, Ott, and others) that the "questioning of my mental/physical fitness was merely in response to my EEOC protected activity." He added that the mayor should initiate an investigation of the claims he had made against the city: "At this point, I believe that one is warranted."

Acevedo told him one day later that he would be returning to active duty as soon as he passed through the Returning Officer Program, considered necessary for those who'd been separated for 90 days or more. Hopkins responded with a 20-paragraph email detailing his concerns about administrative confidentiality and unclear policies. He also cast an accusation directly at Acevedo: "APD claims to be a family, but while I remained in isolation from the Department (probably to force my resignation), not once did the Chief ensure that I was doing well."

He was removed from restricted duty in the middle of June – but sent back home just one week later, after another barrage of his emails to people throughout APD and the city were judged by Acevedo to be harassing and insubordinate. A second IA review followed, and with it, Hopkins' fourth EEOC charge: that this was more retaliation, this time because of disabilities.

Back at home, Hopkins recommitted to beefing up on case law, requested more records from APD and the city (152 requests between last April and this November, though a city employee suggested that many more have been submitted since). He took note when 18 officers (mostly black or Hispanic) sued APD over age discrimination in July, and found an unnecessary-force lawsuit filed by Carlos Chacon in April against Officer Eric Copeland, an equally seasoned officer with a more public track record (see "Investigation Continues in Officer-Involved Shooting," April 20, 2012). He discovered Enemencio Roy Alaniz Jr.'s July lawsuit alleging excessive use of force against Officer Jason Cummins, and took encouragement from black officer Blayne Williams' civil suit against the city in the wake of his 2013 firing (see "Acevedo Fires Officer in Connection With Off-Duty Employment Incident," Oct. 3, 2013).

Finally, in August of this year, Hopkins began taking a growing interest in the case of Antonio Buehler, the police accountability activist who co-founded the Peaceful Streets Project. Buehler became a public name in 2012 after his arrest New Year's Eve at a Downtown 7-11, for intervening in a DWI arrest. Buehler has since waged a very public war against APD and Acevedo, monitoring and video-recording officer activities, taking the city to court to fight Class C misdemeanors (see "Buehler Acquitted," Oct. 31), and filing civil lawsuits against APD and its officers. The Peaceful Streets Project has become a growing consortium of citizens armed with cell phone cameras.

Since its inception, PSP has managed to get under Acevedo's skin; most recently, at a press conference concerning Thanksgiving shooter Steve McQuilliams (see "Hate in the Heart," Dec. 5), the chief commented on PSP's absence during the incident: "When gunshots rang out ... you didn't see some of our critics out there that just love to call us 'coward cops.' ... You didn't see them out there videoing. You saw our men and women riding towards the gunfire."

Since the original New Year's incident, Buehler has been arrested twice more: on Aug. 26, 2012, and a few weeks later, on Sept. 21. Each of his arrests has been controversial, and raised questions concerning APD policies on interference and the use of force. Eventually, Hopkins became fixated on the second arrest: the Aug. 2012 incident on Sixth Street with Officer Justin Berry.

That night, Buehler and other PSP members noticed a young man being detained after a fight with his girlfriend. Buehler filmed the arrest, never getting closer than where he was standing when it began. But after the arrest was completed, Berry walked over to Buehler and arrested him for interference. In justifying the arrest, APD said anybody filming arrests must stand more than 50-60 feet from police activity. "The department takes a strong stance on interference," Cmdr. Troy Gay noted. Hopkins was left to wonder: If someone filming is interfering if they're within 50 feet, why can't the same be true of a drunken, belligerent woman within only 30? Of course, if Buehler had been present the night Hopkins arrested Price, Hopkins might well have arrested him, too. What bothered Hopkins was the difference he perceived between APD's treatment of him and that of Berry.

Response Requested

It's tough to tell when Hopkins realized that he'd have no future with the Austin Police Department, but chances are he knew he was ending whatever remnant of departmental goodwill remained on Sept. 4, 2013, the night before his first suspension's appeal hearing. He fired off 10 different emails to Acevedo and various APD and city staffers between 10:56pm and 11:40pm that night. Topics ranged from information requests to official complaints concerning city staff to requests that somebody issue him a new battery for his APD pager.

Hopkins blew up Twitter that evening, too, asking Mayor Leffingwell and Council Member Mike Martinez what each would do in response to the "unlawful employment discrimination that is occurring at Austin Police." He also tweeted two angry messages to Acevedo (both of which Hopkins has since deleted), and sent another series of emails requesting, among other things, that City Manager Ott place Acevedo on administrative leave "pending a determination by a grand jury."

More emails (there were oh-so-many emails) followed his hearing. Hopkins issued a public information request to Acevedo and Mayor Leffingwell, noting their duty as public officials to comply with the inquiry. Acevedo wrote that Hopkins told the chief "he 'may be notifying' a criminal defendant's attorney of his 'belief' that the City is withholding information." Four days later, Hopkins filed an Internal Affairs complaint against six different superiors for a series of offenses: discrimination, retaliation, and "ignoring or selectively/partially responding to my communications." These were just a fraction of the personal complaints Hopkins filed through the city this summer. Each has officially been either rejected or discarded. Hopkins says the city "never acted" on any of them.

The final nail in Hopkins' professional coffin came on Monday, Oct. 20, shortly after 10pm, when he sent an email to city employees, members of the EEOC, and various attorneys, as well as Admin. Lt. Tyson McGowan and Cmdr. Andrew Michael of APD. The email recounted a number of grievances, many of which he'd spent the past 16 months addressing. But tucked into its second half was the notice that Hopkins had been subpoenaed by Buehler and his attorney, Millie Thompson, to testify against the city, in Buehler's first Class C misdemeanor trial to begin Oct. 23.

Texas Code of Criminal Procedure required that he comply with the subpoena, he wrote, adding that APD policy and Texas Penal Code demanded that he testify truthfully. "However," he wrote, "I understand that the department has previously admitted that the facts contained in the white arresting officer's (Ofc. Patrick Oborski) report/affidavit were inconsistent with the patrol vehicle's video.

"Other video evidence appears to support that statement. I understand that the chain-of-command's review of the R2R in that incident did not result in an Internal Affairs complaint ... Ofc. Oborski was not placed on restrictive duty. Even while his case was pending presentation to the grand jury, I understand that he was still able to work patrol.

"Although it appears that Ofc. Oborski was in violation of Responsibility to Know and Comply and Neglect of Duty because he erred in determination that verbal interference constituted a violation of Interfering with Public Duties ... I understand that he was not sustained/disciplined for dishonesty and for making the false arrest of Mr. Buehler."

The comparisons continue, on and on.

Hopkins received his marching orders the next morning. By Oct. 30, Acevedo made the indefinite suspension public – in a 96-page memorandum. Hopkins was charged with insubordination, unreasonable disruption of the workplace, and acts bringing discredit upon the department.

Hopkins has a ruling pending on his appeal of the original eight-day suspension, and hopes to set a date for a hearing on his termination. Each of his four EEOC complaints is still open, and he has one more: the Travis County District Attorney's Office is currently investigating his complaints concerning the city's unlawful withholding of public information. The U.S. Department of Labor is continuing to investigate Hopkins' claim of unpaid overtime wages, although they did recently award him three hours' worth of unpaid overtime.

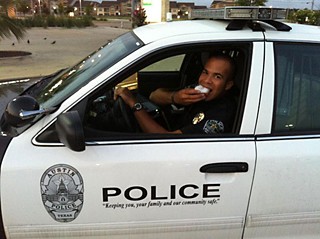

On Oct. 31, the day after he was officially terminated, amidst a hailstorm of tweets, Hopkins posted to Twitter a series of photos commemorating his time with the police department. There's his police badge and nameplate, cadet photo, and shots of him on duty. He's smiling on a squad boat, and writing up a gag citation for a young boy riding a Power Wheels.

In the last shot, he's in a squad car, smiling while chowing down on a powdered donut. "This one is dedicated to you @AntonioBuehler!!" he wrote. "It's an honor to have met someone else who has courage to fight."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.