Water Fall

Between Austin Water's conservation goals and its execution ... lies a shadow

By Nora Ankrum, Fri., June 17, 2011

On the Sunday afternoon this past April when Paul Robbins heard his neighbor pounding insistently on his front door, Robbins happened to be – as those who know him would surely guess – working on his water report: a critical analysis, characteristically unsparing in detail, of Austin Water's conservation programs. He was laboring over the last fine points, intending finally to release the report the following week. It would bear a title – "Read It and Leak" – well-suited to his particular brand of humor, an oftentimes discomfiting combination of the silly and the deadpan, and it would charge that a misallocation of resources and priorities was undermining the Water Conservation Division's achievements, building an impenetrable wall between the utility and the community, and threatening its fiscal health. But the report's debut would have to wait. On this particular day, when Robbins answered his door, the neighbor implored him to leave his house immediately because, just up the street, a wall of flame and smoke could be seen crashing down on his neighbors' homes.

The April 17 Oak Hill brush fire swallowed 100 acres of land and destroyed 11 homes, including the one directly next door to Robbins, but firefighters were able to protect his house, save for his backyard, deck, and part of his front lawn. The wildfire was but one of dozens burning across the state that day, in a year that, only halfway gone, has now seen 2.7 million acres of land scorched, more than double the annual average of the previous five years. Unlike rural Texans, Austinites don't usually experience drought this way. Here, where messages about water come from folksy radio jingles and animated dandelions, nature doesn't show up raging at your doorstep. She tends instead, even at her cruelest, toward drying up all the best swimming holes for the summer, and even then she is politely preceded by a press release – much like the one released May 18 by the Lower Colorado River Authority, announcing that the months since October have been "among the driest in our basin's history" and that the current drought "may be one of the most severe we've seen in decades."

The timing of Robbins' report, delayed till May 4 by the fire, couldn't be more fitting, as Austin faces yet another long, hot, already record-breaking summer, and the city's municipally owned water utility faces budget season. Despite eight years of consecutive rate hikes, Austin Water struggles with waning revenues it attributes to an inconvenient combination of "extreme weather patterns," a down economy, and successful conservation efforts. When rates rise because of conservation, of course, monthly bills for those doing the conserving stay roughly the same if not go down – this "revenue neutrality," as the utility puts it, is the beauty of using less water. But now, ratepayers look to be rewarded for their efforts with a "water sustainability fee," a proposed fixed charge added to every bill to help fund conservation and offset "rate volatility" caused by that triple punch. Conservation is doing what it's supposed to do, says the utility: encouraging the heaviest water users to use less. But "those users pay the highest per-gallon rates," notes AW Assistant Director Daryl Slusher. "So it is not sustainable to depend on these customers for an increasing share of the budget at the same time the utility is seeking to cut their use."

Varying by meter size, the fee would apply to all ratepayers (except qualifying low-income customers), with most residential customers paying an estimated $6. An official proposal will go before council during budget discussions in July. Reaction to the fee has been mixed. Leo Dielmann, chair of the Resource Management Commission, says he's "supportive of the concept." Robbins, on the other hand, is critical, charging that "decoupling" consumption from cost obscures the relationship between how you use water and what you pay on your bill (use more, pay more, or vice versa), taking away the "price signal" – i.e., the inherent motivation to conserve. But Slusher says the measure will help protect AW's "financial health" by stabilizing revenue on "an ongoing basis." The sustainability fee is not, insists the utility, a punishment for good behavior. Those who use less water will still reap financial benefit, and AW's tiered rate structure – which charges heavier users more per gallon, specifically to encourage conservation – will continue to ensure that those heavier users pay disproportionately more.

Still, it's clear that conservation requires more of Austin ratepayers than simply conserving.

Addition by Subtraction

During his hasty evacuation from the Oak Hill fire, Robbins took the time to grab one thing – the computer with his report on it. He did hesitate briefly, intending to spray down his house with water, but, hose in hand, with thick smoke and debris rushing in, he realized he was essentially fighting a fire with a "squirt gun," and abandoned the endeavor. It was a rare concession for Robbins, whose three decades of environmental advocacy have generally inured him to such long odds.

Robbins is probably best known for his Austin Environmental Directory (a sort of green Yellow Pages with wonky policy papers thrown in) as well as his regular Citizen Communications appearances prodding City Council toward better environmental stewardship. But his activism curriculum vitae begins with the dawn of an idea that is now largely institutionalized in Austin: the concept that resource conservation is actually more affordable than waste. In the late Seventies, he was among a handful of locals using this philosophy to fight the South Texas Nuclear Project, arguing that saving energy could actually save money if it freed the utility from the burden of building expensive new power plants. The nuke won that early battle, but today, Austin Energy reflexively promotes efficiency as its lowest-cost resource.

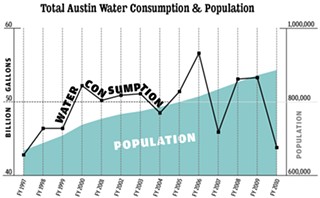

Not so with the city's other municipally owned utility, charge critics, who regularly compare AW unfavorably to Austin Energy in a "why can't you be more like your big sister?" kind of way – especially since City Council's decision in fall 2009 to move forward with construction of Water Treatment Plant No. 4. As AW officials point out, that decision was made only after 25 years in which the utility was able to postpone construction, largely through conservation. But WTP4 critics – chief among them the Save Our Springs Alliance – believed that the strategy would continue to work, arguing that despite population growth (the "real driver" behind the need for more treatment capacity, according to AW Director Greg Meszaros), water use could continue to decline for some time. (So far, it has; see "Total Austin Water Consumption & Population" graph, below.)

Furthermore, critics feared that declining revenues, thanks to declining demand, would make paying for the plant particularly difficult, inevitably leading to "rate shock," a term used at the time by WTP4 critic Kent Butler, a water resources planner instrumental in establishing the Balcones Canyonlands Conservation Plan. Butler argued that conservation needed to happen prior to incurring significant debt (from building the plant) in order to avoid "a pricing conundrum of upward-spiraling rates," similar to what California experienced during the drought of 1987-92: "Customers complained that it seemed like a penalty was imposed on them for conserving water," he recalled, "because they had to pay more on account of using less." When Butler died last month in a hiking accident, the SOS Alliance posted a tribute on its website noting that Austin had "suffered a tremendous loss"; recalling his opposition to the plant, SOS Alliance wrote that "[h]is prediction then that the water rate increases required to pay for WTP4 would be much higher than City staff was willing to acknowledge is now coming true."

Slusher says that regarding conservation, the utility would be in the same financial bind with or without WTP4. Given that the plant's monthly impact on the average residential bill is only 53 cents, he says "the plant is barely in the rate base at this point." By 2016, it will only be about $3.53, he says. Moreover, he argues that AW's rates compared with other cities' are not only "in the herd" but relatively inexpensive at the lowest levels of use, thanks to the tiered rate structure. Robbins counters that in January, AW had "the highest combined residential water/wastewater rates of the 10 largest cities in Texas." Each is using different data in his analysis. Robbins argues his approach is more "accurate"; Slusher says his is the "industry standard." (Much of Robbins' criticism prompts a similar back-and-forth; see "Reading the Meter: The Robbins Report.")

Meanwhile, Slusher offers a slew of reasons why it's better not to have postponed construction of WTP4 – most notably the need for redundancy in the system lest something befall one or both of AW's other, older treatment plants (as briefly did happen last year during Tropical Storm Hermine, when the Davis and Ullrich water treatment plants each lost power for several hours). Opponents dispute this reasoning, continuing to fight the plant even though construction is well under way. Meanwhile, the Place 3 council run-off is proving WTP4 to be the controversy that just won't die, with incumbent Randi Shade – who voted in favor of the plant – accusing challenger Kathie Tovo of unacknowledged designs to halt construction and leave Austin "dry and dangerous." (See "WTP4: Still Bitter Waters.")

With AW citing financial hurdles to conservation, Robbins faults the utility for not at least analyzing potential monetary savings from deferring plant construction. Furthermore, he insists that the plant actually poses a threat to conservation: Given AW's financial commitment to WTP4, "pressure will be high to sell enough volume to justify its expense," he predicts. "There is an inherent conflict of interest in administering programs that save water inside an agency that sells it." Robbins' report includes a list of "immediate" actions the utility should take. The following appears as No. 1: "The Water Conservation Division needs to be transferred out of AWU."

Communication Drought

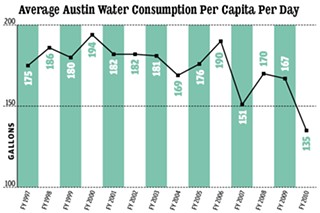

According to Slusher, the utility has a proven record of environmental stewardship. Below its treated sewage discharge in the Colorado River, he points out, the water is rated "exceptional" by Environmental Protection Agency standards. AW's conservation budget is among the highest in Texas, with wildland holdings – nearly 37,000 acres of preserved land – unheard of among the state's utilities. And the Water Conservation Division presides over a variety of water-saving initiatives, including rebates for rainwater harvesting, drought-resistant landscaping, and efficient toilets. As Slusher sees it, the last four years in particular have marked a period of notable achievement, with annual per capita water use trending dramatically downward like a bouncing ball that has suddenly plunged into a stairwell (see "Average Austin Water Consumption Per Capita Per Day" graph, below).

Like Robbins, Slusher has deep roots in Austin's early environmental battles, having covered them in these very pages as the Chronicle's politics editor two decades ago, after a stint at The Daryl Herald (1985-87), a local politics newsletter with a philosophy he later described as being "tough but fair" in scrutinizing "government and players in government, no matter whether their views comported with ours or not." Slusher's time spent in the media trenches is still readily apparent today. "If he doesn't want to answer your question," says Resource Management Commission Chair Dielmann, "he just kind of looks at you and stares with that smile on his face." Slusher left the Chronicle in 1995, served on City Council for nine years, and was later tapped for a new position at the water utility: assistant director of environmental affairs and conservation.

Ostensibly, he was hired for his environmental background in hopes that he'd do for AW what Roger Duncan – the anti-nuke activist turned utility exec – did for AE. Four years later, Robbins sees a different trajectory, in which the Water Conservation Division has become more insular and communication between the utility and the Resource Management Commission – the citizen body charged specifically with advising city staff on matters of conservation – has broken down.

"In the 18 months I've been on the RMC," says Dielmann, "the water utility has been the least cooperative of the departments that have come up in front of us." In a tense exchange at a February meeting, the frustration was apparent. Slusher and Water Conservation Division Manager Drema Gross were presenting their "140 Plan," which aimed to reduce water usage to 140 gallons per capita per day (gpcd) by 2020. This goal was adopted by council in 2010, based on a 2004 recommendation from the Texas Water Development Board. (In 2010, Austin actually hit this target, with water use falling below 140 gpcd; however, the plan aims for a five-year "rolling average" of 140 gpcd vs. Austin's current 163.) The utility had worked on the plan for nearly nine months without any citizen input, despite RMC's repeated requests to be involved; it then presented the plan to council in January 2011 without RMC vetting. Then, when the commissioners saw the report on paper, it seemed still to be lacking in sufficient detail. From the dais, an exasperated commissioner Christine Herbert told Gross and Slusher, "We're getting calls from the public and people coming to speak to us that we can't address [without knowing] where these numbers came [from], what data was used."

"We're supposed to advise council, and in order to advise council, we have to understand the [utility's] thinking," says Dielmann. Instead: "We get the vetted press release; that's it. We don't get anything in-depth. ... That's frustrating at times when you want to kind of dive down into some details or you want to provide some input."

When Robbins set out to write his report late last summer, he hoped to do what the RMC couldn't. He characteristically approached the task like an endurance sport, interviewing current and former AW employees and dogging the utility with a long string of public information requests. ("I think we lost count around 113 separate pieces of information," says Gross.) Robbins says the utility was not always forthcoming. "[S]imple questions, sometimes requiring easy answers, could take 10 working days and longer to answer," he writes in his report. "Material already submitted publicly, such as monthly reports to the City policy makers, could take weeks." After one request took more than two months, Robbins even filed complaints with the Texas attorney general. Gross counters that she actually offered to meet with Robbins in person but that he declined. Robbins concedes that he did turn down Gross' invitation, but says he met on a separate occasion with her and three other staff members to go over his questions.

"I think Paul [Robbins] has done a very good job," says Dielmann, "at diving as deep as he is able to, as a private citizen ... to identify some of those threads that kind of aren't consistent."

The RMC has asked the utility to provide a response to Robbins' report at its meeting on Tuesday, June 21.

What Goes Down Must Come Up

In May 2007, just 10 days after Slusher was hired, council adopted water conservation recommendations put forth by the 2006 Water Conservation Task Force. "That really made water conservation much more of a focus and a much higher city priority, so the division did need to move into a new era," says Slusher. He acknowledges it may have been a "rocky" transition, but not to the extent Robbins claims. Robbins says programs approved then are still languishing today, a charge Slusher and Gross deny. Those programs are part of a plan that's "intended to be implemented over 10 years," says Gross, "and we are actually ahead of schedule" on the overall goal: reducing water consumption by 1% per year.

Nonetheless, she concedes that some programs haven't moved forward as quickly as intended, a setback she attributes to last year's reallocation of staff to develop the 140 Plan. In 2010 council directed staff to look at a new set of strategies for getting Austin to its new goal: a five-year rolling average of 140 gpcd by 2020. Potential strategies had already been developed, at council's behest, by the Citizens Water Conservation Implementation Task Force, but that task force had complied with its directive in abundance, producing some 100 water-saving ideas. "We were really not contemplating additional recommendations to the extent that we received," says Council Member Sheryl Cole, who had served on the original, 2006 conservation task force. Realizing the city couldn't implement "100 different measures all at once," says Dielmann, the RMC approved the recommendations to council with two caveats: 1) that AW "prioritize" measures likely to be "most effective," and 2) that it work with the RMC "to bring in public involvement ... which is really what our charge is as a commission." The first part happened, with AW staff transforming the recommendations into the 140 Plan, but the second didn't.

As staff worked at council's behest on analyzing the recommendations, it became clear, says Slusher, that doing that and also delivering monthly updates to the citizen bodies – not just the RMC, but also the Water and Wastewater Commission and others – would likely push the Dec. 16, 2010, deadline back by a month. "We just didn't have enough people to handle all of that at once," says Gross. Nonetheless, Slusher points out, RMC had already participated in the process, in that two commissioners had been on the task force that originated the recommendations. "I probably failed in that I suggested to RMC I thought we would have an opportunity to bring [the plan] back to them," says Gross. "But it was also clearly intended from the council direction to be a staff-developed plan." As Slusher points out, the council resolution directing AW to create the 140 Plan is mum on the topic of AW working with the RMC. Nonetheless, says Dielmann, "If you read our bylaws established by ordinance, we are to advise council on matters related to water conservation. ... I am not aware that council directed AWU to forgo [that] vetting process."

In any case, when AW Director Meszaros presented the plan to council in January, the RMC had yet to see it.

Selling Short ... or Long

The presentation didn't exactly go over well. Mayor Lee Leffingwell – who as a council member had also been on the 2006 conservation task force – quickly pointed to measures in this new plan that he felt were too extreme. He even called one measure (a limitation on permanent irrigation systems) "draconian," a word that seemed to echo for days, as did the price tag: AW predicted revenue losses of $100 million per year, translating to a 25% to 35% rate hike when combined with the conservation strategies originally adopted in 2007. This presentation of the cost particularly irked Robbins, who felt that Meszaros did not sufficiently emphasize that when rates go up because of conservation, monthly bills will actually go down for anyone using less water. He would later add to his report, in all italics: "There is no net increase in overall costs to ratepayers from the 140 Plan."

The RMC received its official introduction to the plan at its February meeting, by which time Dielmann and commissioner Herbert could barely contain their displeasure. The plan, Dielmann declared, was "set up for failure." One point of contention was AW's approach to calculating the cost. Staff hadn't included cost-savings that would be achieved beyond 2020. For example, the amount of water the city draws from the Colorado River will at some point hit a threshold (201,000 acre feet, two years in a row) at which AW will have to start paying the Lower Colorado River Authority the market rate, whatever it is at that time. Right now, the city expects to cross LCRA's threshold around 2025 – but success of the 140 Plan would delay that trigger point and save the city money: $124 million, Robbins estimates. In other words, the plan looks more feasible long-term than short-term, so why didn't AW calculate those savings?

"That's a good point, and we had internal discussions about that, but ... the resolution says to do a 10-year plan," says Slusher. "You're supposed to do what the council instructs you to do; you don't interpret differently." While he says the utility would "be willing to run things with those numbers," he insists that AW "followed the council directive." The commissioners disagreed. "What's the [directive's] intent?" Dielmann demanded. "It's to exercise water conservation. ... This plan discourages water conservation."

"We think we have a responsibility to tell [council] how much it's going to cost," insisted Slusher. That doesn't mean, countered Herbert, that the plan couldn't have "included some broader vision that would make that plan doable and achievable if that was our goal."

Members from the implementation task force also spoke at the meeting, including LCRA water conservation manager Nora Mullarkey (speaking as a citizen, not representing LCRA). She addressed the measure Leffingwell had called "draconian" – a perceived hard-line approach to limiting irrigated landscape sizes. LCRA had seen success with its customers on similar limitations, she explained, and similar measures had been adopted in San Antonio as well, but if you implement the strategy "without taking into account how it fits into the community, you're going to get a backlash on that, and that was never the intent," she said. Nonetheless, what AW had to work with was not the intent of the measure, says Gross, but only what was written in the task force report – which is exactly, say commissioners, why AW needed the help of RMC members, whose job, after all, is to bridge the gap between citizens and their municipal government.

The RMC approved a recommendation that night asking council to direct AW to work with the commissioners on improving the plan; council has yet to respond.

Regardless of the plan's status, Gross says AW is already moving toward the council-adopted goal of 140 gpcd by 2020, with plans to bring strategies "individually" before council if they require "authorization, including large contracts and changes to ordinances."

Cole says she didn't see the 140 Plan presentation as "negative" but as a "challenge" and a call for change in the utility's business model. "We have not made plans to deal with the financial impacts" of conservation, she says. Others, like Susan Butler, chair of the implementation task force, also take the long view, noting that the 140 Plan has kick-started a dialogue on conservation. But there seems to be a fundamental lack of agreement over what constitutes such dialogue, much less what constitutes progress. Slusher and Gross say they're continuing to work with the RMC, providing updates at monthly meetings; Dielmann counters that "their idea of working with us is presenting a final product ... without any prior input from the RMC."

"An ironic twist in this situation," Robbins writes in his report, "is that while volunteers and AWU staff were working hard on the 140 Plan, the goal was already being surpassed: 2010 was the first year in recent history that AWU has used less than 140 gallons per day per capita." One implication, writes Robbins, is that "careful use, combined with the 140 Plan, may push consumption down even more than expected, making new water treatment capacity even more unnecessary and costly to ratepayers."

Right now, construction trucks rumble on the spot where WTP4 will one day appear near the shores of Lake Travis; it may indeed be the "deepest" lake of the three from which AW can draw water, making it the ideal spot for such an endeavor, according to the utility. But it's hardly as deep as the rift between AW's perception of the task ahead and that of its critics.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.