Reefer Madness

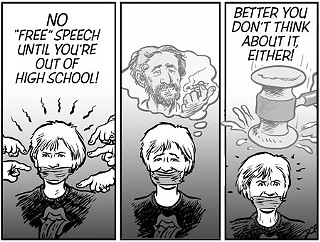

No Bong Hits 4 Students

By Jordan Smith, Fri., July 6, 2007

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, the inane phrase "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" is actually a "pro-drug" message. As such, opines Chief Justice John G. Roberts, the sentiment is unprotected speech – at least when offered by a public-school student, during a "school-sanctioned and school-supervised event." That means that Juneau-Douglas (Alaska) High School principal Deborah Morse was justified in handing senior Joseph Frederick a 10-day suspension after Frederick refused to hand over the 14-foot BH4J banner that he'd unfurled as the Olympic torch relay passed by the school on Jan. 24, 2002.

Frederick fought his suspension, which was upheld by the Juneau school board. He filed suit against the school, which he argued had violated his First Amendment right of free speech. He lost in district court but won on appeal, prompting school officials (represented by Pecksniffian former special federal counsel Kenneth Starr) to appeal to the Supremes. According to Morse and the school board, clearly established school policy prohibits any "expression that … advocates the use of substances that are illegal to minors." The school has a duty to deter drug use, Roberts argues, which "can cause severe and permanent damage to the health and well-being of young people." So it was not unreasonable for Morse and the board to censor Frederick: "We hold that schools may take steps to safeguard those entrusted to their care from speech that can reasonably be regarded as encouraging illegal drug use."

This conclusion, however, relies on the court's assumption that Frederick's "Bong Hits" message was neither political nor religious (two forms of protected speech that could have changed the outcome of this case) and that it was in fact a message meant to advocate marijuana use. This conclusion is valid, Roberts writes, mainly because Frederick couldn't prove that Morse's assumption about the meaning of the message was false. According to Roberts' five-justice majority opinion (he was joined by Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, Anthony Kennedy, and Samuel Alito), the "best Frederick can come up with" to explain his banner's message is that it is "meaningless and funny" – an answer that Roberts says gives the "pro-drug interpretation of the banner … further plausibility." There was simply a "paucity of alternative meanings," Roberts wrote.

In his dissent, Justice John Paul Stevens (joined by David Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg) concludes that the majority opinion does "violence" to the First Amendment. In sticking to the assumption that the message was pro-drug, Roberts and gang have completely ignored Frederick's stated intent, which was to author a silly message that would be broadcast by the media that were trailing the Olympic torch through town. "[T]he school's interest in protecting its students from exposure to speech 'reasonably regarded as promoting illegal drug use' … cannot justify disciplining Frederick for his attempt to make an ambiguous statement to a television audience simply because it contained an oblique reference to drugs," Stevens wrote. "The First Amendment demands more, indeed, much more." Stevens wrote that Frederick's speech should've been protected in part because it did not advocate any illegal conduct. Stevens asserts that the majority has offered only a "gross non sequitur" to justify their position; "laboring" to point out that not all student speech is protected under the First Amendment and concluding that "the school may suppress student speech that was never meant to persuade anyone to do anything."

Although Roberts' majority seems convinced Frederick's speech was not political, it isn't entirely clear that's the case. Frederick has said that the banner was meant to assert his free-speech right – in itself a political act. Notably, when he explained that to Morse during a meeting in her office – quoting Thomas Jefferson, no less – Morse responded by adding an additional five days to his initial five-day suspension.

The majority ruling appears to propose a rickety new standard for evaluating the free-speech rights of students – one that creates a presumption that censorship is fine if the speaker happens to mention the dread bogeyman: "drugs." The backbone of student free-speech rights is the 1969 decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, which concerned a school's attempt to avert a student protest against the Vietnam War. The students weren't unfurling banners but had decided to wear black armbands as a symbol of protest. Apparently school officials didn't like that idea – they argued that the students' comment on the war might lead to "disturbances" that would interfere with school operations – prompting the district to pass a no-armband-in-school rule. The court ruled against the school, finding that "to justify prohibition of a particular expression of opinion, [the school] must be able to show that its action was caused by something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint," the court wrote in 1969. "[W]here there is no finding and no showing that engaging in that conduct would materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school, the prohibition cannot be sustained."

In Frederick's case, Stevens argues that this ruling would now allow officials to engage in censorship based solely on the content of speech – even when, as in this case, the content is ambiguous. Apparently, mere reference to drugs or drug use, even indirectly (as with the words "bong hits"), is the highest hurdle school officials now must clear in order to justify censorship. This, writes Stevens, "invites stark viewpoint discrimination." Here, principal Morse "has unabashedly acknowledged that she disciplined [him] because she disagreed with the pro-drug viewpoint she ascribed to the message on the banner … a viewpoint, incidentally, that Frederick has disavowed."

Roberts does his best to dismiss Stevens' argument (one that would implicate Roberts' participation in viewpoint-based discrimination), but in a concurring opinion, Justices Alito and Kennedy actually validate Stevens' concern that references to drugs alone clear the way for censorship. In the opinion, Alito explained that he joined the majority "on the understanding" that the ruling "goes no further" than allowing a public school to restrict speech that a "reasonable observer" would "interpret as advocating illegal drug use" and that the ruling wouldn't necessarily allow censoring speech that could "plausibly be interpreted as commenting on any political or social issue" – including, perhaps, the wisdom of the war on drugs. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.