The Banks of the Blanco

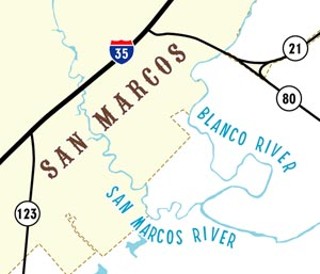

Environmentalists and Hays County clash over river-clearing project

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., July 29, 2005

If you wished to choose a symbol for wanton environmental damage, it's hard to top a clamshell excavator dumping full-grown trees onto a bonfire. That's the scene a group of kayakers found one recent morning at a bend in the Blanco River, just north of where it joins the cool, spring-fed waters of the San Marcos. The excavator, which has a long brontosaurus neck culminating in a clamshell mouth for grabbing things, was rolling toward the very edge of the bank, where a dead, leafless tree lay half-submerged in the water. In one enormous bite, the excavator grabbed the tree, hefted it into the air, and rumbled off to drop it onto the towering fire. The scene was loud and ugly, and it sure looked like evidence of precisely what the kayakers had come to the river to find: that a county-managed river cleanup was progressing more zealously than could possibly be beneficial for its banks.

Sitting in his yellow kayak, watching the tree-eating beast in action, Hill Country River Adventures owner Dub Dietrich looked distressed. "Those fallen trees are necessary for the health of the river," he said. Dietrich was dressed in head-to-toe quick-dry; on trips he drives an ancient, hospital-green Chevy suburban with a cracked windshield, and around his neck wears a stylized fishhook – a Maori symbol for luck on the water. When he first saw the county clearing brush and fishing logs out of the river, he called the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club, which promptly began demanding that the county cease and desist the hacking and chopping. Rivers don't need to be cleaned, the environmentalists insist; both living vegetation and fallen trees protect the Blanco's banks from erosion by buffering the flow of the water. The county just as firmly defends its project, which is funded with a $750,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Natural Resources Conservation Services and $250,000 of state money. They're not out to tear up the river, project managers say, they're simply out to clean up the huge piles of debris that accumulated in the deadly floods of 1998, 2001, and 2002.

When you're floating in the water on a clear summer day, with the smoke from the burning trees hanging in the air, the cleanup sure looks ugly. But like the river itself, things may not always be what they appear. "From a natural standpoint, it would be good for that debris to stay in the river, but if you get enough of it, the next flood that comes through could lift those logs up and float them downstream," says Richard Nelle, a wildlife biologist who writes about riparian habitats. Floating logs blow out bridges, or they jam up into natural dams that send the water spilling out of the river and into people's living rooms. "[The debris piles] are good or bad, depending on how you look at them."

All Clear

Dietrich and his companions had hit the river a few miles north of the work site, carrying their kayaks over bare gravel that, Dietrich said, weeks back had been thick with greenery. The group included campground owner Tom Goynes, who is also president-for-life of the Texas Rivers Protection Association, and two Sierra Club members. Paddling downstream in the silty blue-green water, Dietrich and Goynes pointed out bank-spot after bank-spot that once was brushy, but now was bare. Goynes, who is sunbaked and scruffy as any lifelong river rat, speculated about the managers' motives – whether they were trying to manicure the river to give it a more tame and tidy appearance, or whether maybe it was just all about boys and their big, powerful toys. Whatever the motives, Goynes is certain the long-term results won't be good. He pointed to a pair of cypresses on the naked gravel bank, their root clusters dripping into the water like wax on old candlesticks. "They left these two lonely cypresses with nothing to protect them," Goynes said. "They'll be on an island before you know it."

The kayakers aren't the only ones grumbling about the cleanup. Dianne Wassenich of the San Marcos River Foundation says she's heard complaints all year. From her own experience during 20 years of volunteer work on the nearby San Marcos River, she also has no doubt what the project's long-term results will be.

"We see it all the time," she said. "People buy land and decide to make a nice picnic spot by river, they clear and hack all the vegetation, and the next time the flood comes, it takes half of their land with it. We're very aware of the problem and we're astonished the county is doing this."

Holding the Land

Not surprisingly, the view is somewhat different from above the river banks. It's comforting to think of nature as, well, natural, but the Blanco, like most Texas rivers, is anything but. Every year, development brings more impervious cover to the Blanco's 480-square-mile watershed, which sends more and faster runoff into the river. Hardy but non-native species, like the Johnson grass sprouting up waist-high everywhere, have made a home for themselves along the river's banks. Meanwhile, every rain washes a little more gravel from riverside mining operations into the channel. The river, says Hays County grants administrator Richard Salmon, is changing.

Salmon has lived in the San Marcos area his whole life. He grew up on a sorghum farm; he used to work for the state promoting sustainable agriculture; and as he bounces around work sites in his white Ford pickup, he can point out all the ways the area has changed. It's not just the Cabela's, or the coveys of parrots you see in the trees, which you never used to see north of the Valley – (global warming, he theorizes.) It's the bridge near Texas State he used to dive off when he was a kid, where the water's now barely a foot deep. It's the mobile home park that's not there anymore because everyone got flooded out. And it's those big piles of debris.

"Because the runoff is so much faster, we were finding these humongous piles of trash," he said. "We found butane tanks, septic tanks, people's decks, tires, all kinds of stuff that had just floated off."

Not only were the piles a flood risk, local kids kept torching them one summer when arson was all the rage. The debris, Salmon insists, had to go. While some live vegetation must be destroyed for crews to get at the dead stuff, Salmon insists they are trying to preserve as much vegetation as possible, following a contract that stipulates only downed trees and small-diameter live vegetation can be removed. He admits the cleaned-up areas look pretty raggedy at first, all that bare gravel baking in the sun, but, he says, just you wait. Unlike the landowners who try to keep their tracts cleared and mowed, the county is letting the banks revegetate, which happens almost unbelievably fast. At one spot that was cleared in May, the sycamores and hackberries are already several feet tall, and the willow and pecan seedlings aren't far behind.

And while the project's critics argue that the fallen logs should stay in order to prevent erosion, Salmon disagrees. "The debris doesn't stop the erosion, the plants' root systems do that," he says. "When you take out the debris, those plants can come back stronger," he said.

As the River Runs

Another of the project's managers, Cliff Caskey, agrees. With leather-belted blue jeans and a silvery penumbra of buzz-cut bristle, Caskey looks a little like Hank Hill's obstreperous daddy on King of the Hill, except that he smiles a lot more. Caskey knows the name of every plant in sight, and he's happy to point them out to you while careening around the work site atop a sputtering blue all-terrain vehicle to show off the remaining heaps of logs to be removed. One such pile was a couple dozen feet long and as tall as a man, with a very beat-up Dumpster sitting up top like a maraschino cherry. At the moment, the pile was a good 50 feet back from the bank, but Caskey said a good rain could change that quick. "If all that stuff floats down river, and causes a logjam that makes the river come up out of its banks and kill two or three people, that's not right in my mind," Caskey hollered over his Kawasaki. "If by doing this we save one life, it's worth it."

Caskey has a master's in biology and insists that he knows full well how to care for riparian areas. Frankly, he resents the accusations against the project. "We might be a little on the stupid and ignorant side," he said deadpan, "but I think we have a pretty good idea of the situation and what it calls for."

For as long as Americans have been trying to protect the environment, proponents of a hands-on, managerial approach have always clashed with hands-off, romantic types. However, with houses sprouting up and pavement spilling all over the Blanco's watershed, the question of what exactly the situation calls for will likely be ever harder to answer. The Blanco cleanup project will be finished in a matter of weeks; but the debates on its banks are by no means unique. In Austin, for example, the city is currently struggling to manage an increasingly flood-prone section of Onion Creek – city managers want to buy creekside land for parks, while neighbors urge them to start instead by clearing up the debris.

Down along the Blanco, as the people in the river and the people on the banks peer at each other with suspicion, both have ideas for closing the gap. Wassernich of the San Marcos River Foundation wants public seminars on how to care for the river. Project manager Salmon would love for the critics to help organize volunteer teams to plant native grasses and trees. And the next time the rains come, the river will do what it wants. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.