A Liquid Proposition

We Bought the 'Prop 2' Lands to Protect Austin's Water -- Can the Earth and the City Do the Job?

By Dan Oko, Fri., July 6, 2001

"We've got rattlesnakes on this property, so watch where you step," says William Conrad, as he climbs out of the white Ford Explorer with the city of Austin emblem emblazoned on its side. Dressed in Wrangler jeans and a pale straw cowboy hat, wearing a sizeable mustache that wouldn't look out of place on a walrus, Conrad (who goes by just plain "Willy") looks very much at home on the range. As he makes his tour of several parcels of land recently purchased by the city to help preserve water quality and quantity in Barton Creek, Conrad's caution extends to more than just snakes. Last year, Conrad was hired by Austin's Water and Wastewater Utility to manage lands in what are known as Barton Creek's "contributing and recharge zones": areas in the Edwards Aquifer that eventually drain into Barton Springs and Town Lake and contribute as much as 30% of Austin's annual drinking-water supply.

Before he answered the call to return to Texas, where he was born and raised, the 47-year-old Conrad worked for the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture in Elko, Nevada, where the Sagebrush Rebellion, a movement of private landowners with little tolerance for federal policy, focuses considerable heat on public servants. Fortunately for Conrad, rather than representing the heavy hand of regulation on a resentful populace, he was employed by the USDA's Natural Resource Conservation Service in a program designed to help landowners cope voluntarily with rangeland management issues. To hear Conrad tell it, the work involved designing and implementing conservation strategies and ecosystem recovery plans for a generally conservative group of ranchers. Not incidentally, the work helped him develop superior skills for building consensus across constituencies. "Some people like to call it conflict resolution," says Conrad, "but I consider it conflict avoidance."

Such tools should serve Conrad well as he continues to get used to Austin traffic, and turns his attention to the daunting task of how to wring drinking water out of 15,000 relatively arid acres spread across western Travis and northern Hays Counties. Although the properties for the most part have been taken out of the development matrix (a few landowners have retained partial development rights, and a couple of the properties are being considered for resale), they still have a long way to go if they are to yield the sort of return on investment the city is hoping for -- Conrad believes that with a little love and tenderness, he might be able to increase the amount of water flowing into the aquifer from some acreage by as much as 100,000 gallons annually per acre. With high growth rates and continued development throughout the region, the need for such programs is self-evident, as new residents create a demand for more water, and increased building limits the amount of clean water that flows through area streams.

Conrad has a big job ahead of him, one made all the more difficult by virtue of the fact that he expects to rehabilitate the land and pay for his staff on a shoestring budget of around $300,000 a year. Conrad currently faces what may be the biggest hurdle of his new career: the adoption of his draft management plan for what are formally known as Water Quality Protection Lands (WQPL). Since early June, the plan, which outlines a set of recommendations and not regulations, has been wending its way through the Austin bureaucracy, and is under review by public entities at the municipal, state, and federal level. If all goes well, Conrad will release the document to the public next month and present it before city council before the end of August.

But until he knows what his bosses think of the plan -- which is the result of an intensive, months-long stakeholder process, involving 25 groups ranging from the Texas Cave Management Association to the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce -- Conrad won't say much about what his proposed management strategy might be. "The idea is to focus on the needs of the lands and the needs of the stakeholders," he says, choosing his words carefully. "If we are talking strictly about water quality and quantity, a lot of the land is not quite where we would want it to be." The basic challenge for Conrad and the Utility is to enhance both water quality and quantity by shoring up ecological components on many of the properties, such as by planting native grasses that will help diminish erosion and also help the soil store water. Conrad must also consider demands for public access while contending with the threats posed to Barton Creek by continued development across the Central Texas landscape. In terms of strategic particulars, Conrad allows, "Vegetation management will be one of the keys to our water enhancement program."

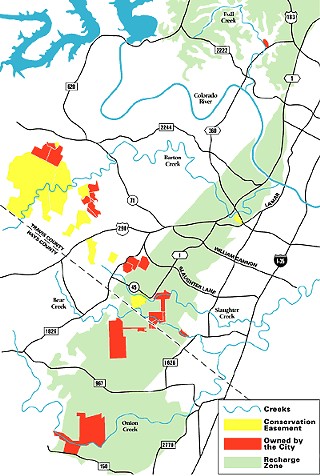

The WQPL effort got its start back in 1998, when Austin voters passed Proposition 2, providing Water and Wastewater with $65 million to buy 15,000 acres of land and development rights over the Edwards Aquifer. With desirable tracts identified, the Utility then evaluated these properties according to a long list of criteria, such as location and proximity to existing public holdings, including parks and preserve lands, size, potential for development, and existing regulations that might protect water quality regardless of ownership. As of last September, the Utility had purchased 7,169 acres outright (meaning the land now belongs to the city) and development rights for an additional 7,709 acres in conservation easements (see "Conserving the Easements," p.26), which means the land remains in private hands but sensitive portions will never be developed.

Despite the fact that many parcels show signs of poor management, overgrazing, and general neglect, the city did manage to find some diamonds in the rough. While budget constraints may hinder some restoration efforts, supporters of the effort note that open space beats development any day of the week. Jeff Francell, formerly with the local chapter of the Nature Conservancy, a national land preservation organization, coordinated many of the Prop. 2 conservation easements and purchases for the Utility before moving on to his current position as Public Lands Acquisition Manager for Texas Parks and Wildlife. Noting that the lands were selected with an eye on not just water quality but wildlife habitat and recreation potential as well, Francell says: "This land is forever. We'll own this land in periods of prosperity, and we'll own this land in periods of poverty. ... Even if we don't have the money to do what we want right now, at least we know it will be there when we are able to pay for it."

A Shifting Mosaic

Conrad's 18-month-long stakeholder process for building consensus appears to have served him well. Turning up detractors for the WQPL project is not easy, but there are several parties still holding their breath. Representatives from a variety of recreational groups who attended the stakeholders meetings, from horseback riders to soccer players, hope that some of the Utility's open space might someday be able to accommodate trails, ball fields, birding blinds, and the like. And members of the environmental community see Prop. 2 as a good first step, but worry that WQPL implementation will limit ecosystem restoration to water recruitment rather than integrating wildlife habitat, especially for endangered species such as the golden-cheeked warbler. Austin greens also worry that the city will rest on its laurels instead of aggressively pursuing further opportunities to buy more open space for such programs as the WQPL and the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve (BCP).

Perhaps predictably, Bill Bunch, lead attorney for the Save Our Springs Alliance, is willing to give voice to a wide range of concerns. "In my view, there's protecting the aquifer as a drinking water supply, and then there's looking at the Springs as the soul of the city," Bunch says. "Unfortunately, this needs to be viewed as a first step -- not a first and last step. We need to ask, what is it worth to Austin to save the Springs? What will it cost Austin to lose the Springs?

"The window is closing on the ability for the city to lay hands on a lot of these [additional] properties. If it costs another $200 million or $500 million, then we've got to figure out how to come up with that money. When we can come up with $150 million for road expenditures, you would think we might find more money to preserve Barton Creek. I really feel it's more important to figure out how to protect the soul of the city than to pave the world." In addition to proposing another bond issue, one concrete recommendation Bunch has for raising money is to make sure if and when any of the WQPL holdings go on the block, the city gets paid full market value for the land. "There's been some talk about offering some sort of limited development deal on some of these tracts," says Bunch. "We have some strong ideas about that, and if they're going to do that, they have to be extremely careful, and make sure to maximize revenues."

For the most part, Conrad appears more comfortable in the role of environmental engineer than real-estate agent (or, Heaven forbid, political point man). Walking the ridgelines and valley bottoms that define his jurisdiction, he points out areas where erosion may be contributing sediment to the watersheds linked to Barton Creek, looks for spots where invasive young junipers might be susceptible to prescribed burns, and discusses the potential to establish grassland savannahs where cows and bulldozers have helped denude hillsides. A former federal employee, he's also sensitive to regulations such as the Endangered Species Act, and has been consulting with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to determine the best way to mitigate potential impacts on endangered species habitat -- especially that of the golden-cheeked warbler, as well as the Barton Springs salamander and invertebrates found in many caves on the new city land.

"People talk about ecosystems and they think about a series of linear events," he muses. "But we think that what we had here was a shifting mosaic, a chaotic system subject to chaotic events." He also says that any discussion surrounding the sale of parcels remains premature.

For the time being, Conrad says, the trick is to figure out how to balance the two central prescriptions laid out in the original bond. His responsibility is to increase water quantity, as well as improving water quality. On some properties, that may require decommissioning roads built by eager developers who sold out to the city, or eliminating copses of trees such as juniper and cedar, which tend to use up more water than the grasses and brush that can be found elsewhere. Soil profiles, Conrad says, were documented throughout Travis County back in the 1970s, and hydrologists and soil experts have continued to examine how and where water drains to Barton Creek and other streams included in the section of the Edwards Aquifer covered by the WQPL (see map, right).

One of the peculiarities in water conservation in Austin, Conrad explains, is that water drains more quickly in the Hill Country than it does in other areas -- in a matter of hours and days, rather than months or years. This raises the stakes when it comes to augmenting the aquifer's carrying capacity, and requires a variety of approaches to help counteract the impact of increased runoff from development and the pollution it carries. In addition to Barton Creek, Bull, Slaughter, Onion, and Bear Creeks have also been designated distinct management units under the forthcoming water quality plan.

Finding Good Stewards

The final hurdle Conrad must overcome is how to accommodate demands for public access. Although Prop. 2, unlike the bond elections for various parklands or preserves such as the BCP, doesn't dictate any recreational access, Austin residents have come crawling out of the woodwork with hopes that at least some of the WQPL will help offset the loss of open space and recreational opportunities elsewhere. For the time being, it looks as if the most likely activities allowed on the water quality tracts will be passive, such as hiking and bird watching. The demands for field care and watering make soccer unlikely, and opportunities for sports like mountain biking and horseback riding remain uncertain. One of the problems with allowing access, says Conrad, is that his department just doesn't have the budget to hire someone to police the properties or maintain facilities.

Still, he says, providing opportunities for the public to get on the land can build a constituency for the program, teach people about the importance of water conservation, and maybe even provide them with some tools to achieve similar effects elsewhere. In the end, it's worth noting that public access will only be permitted on tracts the Utility owns outright, and the more than 7,000 acres of conservation easements included in WQPL will remain off-limits to recreation. "The Utility is not in the parks and recreation business," Conrad says. "We are not going to be able to raise rates to build trails or maintain facilities. Basically, I have my hands full. ... We've tried to make it clear to our stakeholders that they are going to have to provide the resources. I have confidence that if we have a strong commitment on their part, we will be able to provide some level of access."

That proposal suits Hill Abel, owner of the Bicycle Sport Shop and an active proponent of multiple-use trails. In fact, despite the fact that access has only been tentatively proposed at two of the seven sites identified as suitable for recreation, he seems genuinely pleased at the outcome of the stakeholder process. "The challenge is to show that we can be good stewards of these lands," he says. "If we don't do that, people will kick us off. So, we see this as a real educational opportunity."

Amy J. Marvin of the Texas Equestrian Trailriders Association is a little more circumspect in her evaluation of the stakeholder process. "Basically, I have an 'I'll believe it when I see it' attitude," Marvin says. Clearly, she's not the only one wondering what comes next. Steve Windhager, director of the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center's Landscape Restoration Program, performed the biological surveys on the whole WQPL, and says that the efficacy of these lands to help solve the problem of water supply for Austin will ultimately turn on economics as much as it will on ecology. "The biggest problem is that the city has only provided limited finances for maintaining water quality and quantity," he says. "In order to meet the recommendations, they're going to have to increase staffing or budget lines. If they choose to ignore that, they're going to end up going against the bonds." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.