Deep Blues From Gatesville

Reporter Amy Smith Profiles Drug War Casualty Amy Smith: Pieces of a Life From a Texas Prison Cell

By Amy Smith, Fri., March 16, 2001

It's not every day you see a woman chained to her bed in a maternity ward, but that was how Amy Louise Smith spent the first eight days bonding with her newborn son, before saying goodbye for the next 20 years. In 1992, when Amy Smith was seven months pregnant with her third child, she went to prison on a drug conviction. She carried her pregnancy to term in the Dallas County Jail, and had her baby at Parkland Hospital.

Twenty years. No one believed that Amy would get the maximum penalty for possession of $20 worth of crack cocaine, or $40 worth if you include her priors. Nor did anyone believe then that she'd still be locked up today, going on 10 years. She was very small time -- buying a dime rock here and there on street corners or in crack condos in North Dallas. She always knew where to go. Amy had been using drugs off and on since she was a teenager, including prescribed dosages of lithium to treat her manic depression. She had been in and out of rehab for years, but nothing seemed to take. So when a criminal district court judge in Dallas got hold of her case on March 11, 1992, he decided to max her out at 20 years, for less than a gram. Her sentence carried an "enhancement" because it was her second offense. "Good luck," the judge said. Amy reeled in disbelief.

"I thought he was kidding," Amy says, recalling the seemingly relaxed atmosphere of the courtroom as the judge worked his way down the docket. "They had been sitting around talking about where they were going fishing that weekend, and then the next thing I know the judge is giving me 20 years." Amy hadn't bothered contesting the charge. She knew she was guilty. The cops had caught her red-handed, even though she now believes they searched her illegally when they fished a small baggie out of her jacket pocket. When she entered her plea a week earlier, she thought she would get two years, tops. Her public defender had asked the judge for probation, but if he put forth a compelling argument in his client's behalf, you wouldn't know it by reading the court transcript. Not that Amy's own performance was any better. Her testimony conveyed the sweaty desperation of an addict who will say anything for a second chance, or a third. She perjured herself and exaggerated truths with promises of a bright future as a "very good citizen."

In truth, Amy was a complete mess. This is how a lot of drug users end up in the custody of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, when their lives are in shambles and their families, at least the ones without much money, have all but given up on them. Drug offenders -- most of them serving time for possession -- make up about 20% of Texas' burgeoning inmate population. Last year, the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics ranked Texas No. 1 for having the largest prison population in the nation. As of last August, the Texas tally stood at 133,680 -- more than double the number of inmates incarcerated when Amy came into the system. Amy, who turned 41 in November, is also one of nearly 8,000 women in TDCJ custody, and among 2,700 women who are considered nonviolent drug offenders.

Amy's story is not unique. Indeed, her history of abuse, depression, and drug addiction is only too typical: One in three women in prison are there for drug offenses, and the majority of women prisoners have a history of abuse and depression.

In Texas, most female inmates -- including the seven on death row -- are housed in various low-slung prison units just outside the city of Gatesville, about 100 miles north of Austin. For one reason or another, prison management bounced Amy from unit to unit over a period of several years. Now she makes her home in one of seven "satellite" compounds of the Gatesville Unit on State School Road. Amy's satellite is called the Terrace. Except for the imposing eight-foot fence topped with razor wire, the Terrace resembles a 1950s-era elementary school that has survived decades of budget cuts.

Amy works the night shift on a cleaning crew, but usually there's not much to do except read. She drifts off to sleep after breakfast, and then hits the pill line at 3pm for her antidepressant. Mail call comes in the evenings, after chow time. That's the high point of Amy's day. She sees a therapist once a week and has twice participated in a 12-week stress-management workshop for inmates. If she's not on restriction for mouthing off or for some other infraction, she spends time in the day room or the rec area, or she goes to the commissary where she buys her personal items with the money that her husband -- the father of her two young sons -- sends each month. The boys' father, Mark Fair, has stuck by Amy all of these years, and he and the kids travel from their home in the Colony, north of Dallas, to visit Amy for a couple of hours once a month. Mark and Amy met in rehab 11 years ago. Mark has been clean since December of 1988. It's been about three years since she has heard from her 15-year-old daughter, who lives with Amy's ex-husband, and this estrangement leaves her deeply saddened. They say that separating a mother from her children is the harshest form of punishment, but when Amy sees her two youngest kids, Kendon, eight, and Cameron, 10, she feels doubly punished: She is allowed no "contact visits," and a hard, transparent barrier separates her from her sons. "I haven't touched my babies in five years," she says, "because of disciplinary [action]."

Amy can have one non-contact visit per weekend, so she likes for people to come on the days that Mark and the boys don't. One visitor, Jim Berry of New Braunfels, serves as Amy's spiritual adviser and makes the drive to Gatesville about three times a year. Between visits, Berry, a retired government employee, sends Amy books that he buys for a quarter from sales put on by the Friends of the Library. "It's too bad," says Berry, "that people who aren't clever enough, or who don't have enough money for a good lawyer, get sentences like Amy's. Her sentence is just so out of proportion. It's nonsensical."

Ironically, if a judge had sentenced her two years later on the same indictment, Amy would have been home by now. In 1994, the Texas Penal Code underwent changes in sentencing guidelines, making possession of less than a gram of cocaine a state jail felony, meaning drug offenders, along with other low-level felons, are housed in separate state-operated facilities created under the new law. Now the sentencing range for less than a gram of coke includes one of three options: 180 days to two years in a state jail, one year in a county jail, or up to five years probation and a $4,000 fine. Unfortunately, the new guidelines had no retroactive effect on inmates already serving lengthy sentences for drug offenses. Another option judges have now is to place drug offenders in Substance Abuse Felony Punishment (SAFP) programs, where offenders are confined for nine months of intensive treatment. Success rates, however, depend largely on the additional resources available to the offender outside of the state program. The Criminal Justice Policy Council, a state agency acting independently of TDCJ, reports that the fewer treatment facilities there are available to substance abusers, the higher the recidivism rate for those who don't continue treatment after their release from the state program.

Good Time Blues

On the face of it, the drug conviction isn't the only reason Amy's prison time seems infinite. She has lost more than 1,800 days of "good time" -- six years' worth of time that she could have sliced off her sentence had she stayed out of trouble. But even model inmates are having a hard time getting their walking papers. TDCJ implemented some get-tough rules in 1995 under former Gov. George W. Bush, making it harder for inmates to accumulate good time and become eligible for parole review. The policy change effectively guarantees TDCJ a full house, and justifies a bloated budget of $5 billion. Meanwhile, more inmates are serving longer sentences, the annual number of parole board approvals continues to shrink, as does the number of corrections officers, whose work force currently operates with a shortfall of 2,700 officers.

This throw-away-the-key philosophy means that even nonviolent offenders like Amy end up serving longer sentences -- costing taxpayers $40.65 per day for each day served. If Amy is fortunate enough to make it through to next fall without a major disciplinary infraction, her status will be reviewed by prison officials and, based on that outcome, she may get a second shot at a parole board review. Her upgraded status for good behavior would also earn her contact visit privileges with Mark and her kids. The parole board is charged with screening the prison records of eligible inmates every year to determine their readiness for return to society. (After a decade of political pressure to reduce parole numbers, the legislative mood on parole seems to have slightly lightened this session -- if not from compassion, at least from tightened budgetary limitations.) In a case such as Amy's, said TDCJ spokesman Larry Todd, the Parole Board members would study the success of her rehabilitation and weigh the merits of her plan for a life outside of prison.

In her defense, Amy and her family say she didn't start racking up citations until an incident with a corrections officer nearly sent her over the edge. At the time, August of 1993, Amy was housed at the Mountain View Unit in Gatesville. When Amy lodged a verbal complaint against the officer for making sexual advances toward her, officials responded by transferring her to another unit, she says. As it happened, the officer, a captain, was fired a year later for inappropriate behavior with another female inmate. But Amy still wanted to bring closure to her own charge against the officer. In 1996, she filed a federal lawsuit seeking damages for claims that Capt. Porfirio Franco, a 10-year corrections officer, groped her breasts and buttocks, tried to kiss her, and made suggestive remarks. A U.S. District Court judge dismissed the lawsuit without prejudice -- meaning Amy has the option to refile -- because Franco couldn't be located. (Efforts to reach Franco at his last known workplace -- a U-Haul rental shop in Killeen -- were unsuccessful.) Amy also named six other prison officials in the lawsuit, including two assistant wardens, charging that they failed to properly investigate and discipline Franco. In an April 1996 Waco Tribune-Herald story on the lawsuit, Franco denied the allegations and described Amy as a "psych" patient with frequent mood swings. Similarly, TDJC officials went on the offensive and told the Tribune-Herald that Amy had spent time in solitary confinement on six different occasions and that "she had a history of making threats and refusing to obey orders." The story doesn't mention that most of Amy's "history" began after the alleged sexual assault.

For her part, Amy volunteers that prior to the incident, she had been engaging Franco with tales from her days as a topless dancer. "He came on to me and I rejected him. He thought he was this hotsy-totsy thing that I just had to have." Officers are strictly forbidden from having any sexual contact with inmates -- consensual or nonconsensual -- and more recent laws and TDCJ policy changes have deemed such behavior a felony offense, according to a TDCJ spokesman.

"I tried to do things the right way and they basically told me to shut up and not say anything," Amy says. "But you know what I would have done differently? I probably would have let him take down his pants and then I would have screamed rape."

After the Franco episode, it was all downhill for Amy. "They sent me over to Sycamore and then I started getting all of this disciplinary stuff," she says. "Then I found out my little boy was sick, he was barely a year old by then, and I was insomniac really bad because, when something really bad happens to me and there's a change of events, I go kind of off kilter. So I'm over there at Sycamore and I'm just kind of losing it." But if there was anything positive that came from going off-kilter, she says, it's that it forced her to talk more openly with the prison therapist about some issues involving past sexual abuse. "I had to get inside and deal with that," she says. "I just had to."

Nevertheless, Amy's infractions, both major and minor, have continued to add up. Says Mark, the father of her sons: "Amy brings some things on herself because she can be confrontational, but I don't think she brings it on herself all of the time." He recalled one occasion when a corrections officer mistakenly thought Amy had reached the end of her allotted two-hour visit with Mark and the kids. "I was sitting there watching the clock and I knew we had 20 minutes left," says Mark, an applications engineer for a Dallas area tech company. "But the guard insisted our time was up. So finally, Amy got up and questioned the guard about it, and they let us continue our visit. But it was like the guard was saying, 'Okay, I'll let you off the hook this time,' as if Amy had done something wrong. I think if I hadn't been there Amy might have gotten in trouble for questioning authority or something."

Sometimes, Amy says, she feels "set up" by a few of the officers, but adds that she gets along well with most others. "I'm not going to sit here and slam the whole system. It's not horrible. There's some really good people here who are supportive and understanding and compassionate. The ones that I have a problem with are the ones who are kind of stuck here, they have to have this job because of the area or whatever, and they don't have any other choice. So they're kind of resentful toward the inmates." Amy admits that she is sometimes the source of her own troubles. "I know I act out and I can be arrogant, but I try not to be," she says. "I get upset sometimes but if you know me, you'll be like, 'Oh, there she goes again, don't let her drink another soda' ... I mean, I get on my own nerves sometimes. But that's how it's always been with me, you either really, really like me -- or you can't stand me."

Miss Deja and the Vus

In her youth, Amy says, her home life was a study in emotional flashpoints. Her father, who died in 1991 at the age of 55, was a serious alcoholic. He had sobered up in his last years, but a lifetime of hard drinking had already taken a toll on his body. Her mother struggled with depression and tried to hold the family together.

Born in Pennsylvania, Amy grew up in Maryland, the second of three daughters. Her electrician father worked for many years in the pressroom of the Washington Star, until the newspaper folded and Amy's family moved to Florida. Later, Amy came to Texas "on an adventure" and settled in Dallas where she landed a job as a dancer at Baby Dolls. This is where she met the man who eventually became her ex-husband.

Amy's dancing career started at the youthful age of "barely 17," when she discovered the thrill of being in the spotlight. "I was an ugly duckling," she says. "I grew up a tomboy -- my father would even call me his son. I never wore heels or make-up or anything like that." Her entrée into the business happened out of the blue one day when some fellows asked her if she wanted to compete in a topless dancing contest at a club down the street. The top prize was $75. "I had a fake ID and everything, so I went into this club and it looked like fun. The girls took me in the back room and combed my hair and put some make-up on me, and they loaned me some shoes and a G-string. I got up onstage and won the $75, plus in tips I made -- I can't even remember how much I made -- a tremendous amount, and I think I was hooked from then on, because of the attention. I was always one for wanting attention. I'm kind of needy."

Amy is quick to point out that she wasn't just any dancer; she was a classy dancer. She found an agent and she started studying the choreographed steps of the Gold Diggers, a dance troupe, on television. She learned flame-throwing techniques. She dazzled her audiences by setting herself ablaze. She danced seductively with a boa constrictor. Her stage name was Miss Deja and her backup dancers were the Vus. Sometimes she went by the name of April, or Cricket, the nickname she'd had since she was a child. "I got to know the regulars," she says. "They'd tell me all their problems and I would make a point to keep up with sports and the scores and everything. I never liked to be touched, though. They have lap dancing now, it's more degrading than it ever was. At the time, I never, ever drank or used cocaine at work, although after hours my habit developed."

The more drugs she did the less she was able to work. Sometimes she'd stumble into this pattern for months on end, sometimes years at a time. "Then I'd go clean and get on a health kick and I'd take a class -- I loved taking cooking classes, or weaving, or pottery, or whatever."

Amy's younger sister, Karen Monroe of Winter Park, Fla., is familiar with Amy's swings from heavy drug use one year to clean living the next. "If she's doing OK, then her house would be absolutely immaculate, but if she was on a downswing and back on drugs, her house would be a pigsty," she says. "The last time I saw her, it was '88 or '89. I walked into her house and I saw all of her clothes on the floor and a pile of dirty dishes in the sink, and I thought, 'Uh-oh, she's at it again.' What's unfortunate about Amy," her sister continues, "is that she's amazingly brilliant, and so creative and talented, yet she's never really had a chance to develop her talent."

When She Gets Out --

Even with its thriving prison industry, or perhaps because of it, the outskirts of Gatesville creates an aura of a ghost town. It's easy for visitors to lose their direction as they navigate through a web of institutional-style buildings sprawled across a prairie-dull landscape. Amy knows little about this Central Texas vista, except for what she sees from the inside looking out. In the long corridor outside the chow hall at the Terrace, a sign hanging from the ceiling warns the inmates: "No Talking, No Hable." A dozen or so women wearing prison-issued white uniforms file down the hallway in heavy silence, casting curious glances over their shoulders at two visitors, a reporter and a photographer, who have joined Amy in the library.

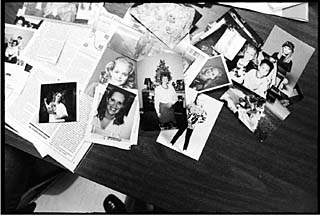

Amy has done her hair up nice and she's wearing make-up. She smiles. "I'm not as nervous this time," she says. The last time, on a dreary gray Friday before Christmas, Amy tried to squeeze her life story into a two-hour synopsis. She choked up a few times, talking about her kids. This time, in late February, Amy brings with her a stack of family photographs. She holds up the pictures one at a time. "This is my mom and my sister, Karen, the one I told you about? They're down in Florida. This one's Brittany as a baby. And this one, I wanted to show you how I've changed over the years. This was right before I got arrested ... and this one here, this is the last time I saw my daughter ..." If Amy were to serve out her full sentence, her eight-year-old son will be 21, her 10-year-old son 23, and her 15-year-old daughter 28 when she gets out of prison.

When she gets out, Amy says she has her work cut out for her. The first big job, she notes, will be to find a home for her and Mark Fair and the boys. The three of them currently live with Mark's parents. "I really want to get situated in my home. I see myself getting adjusted to making meals, being a mommy, getting to know my kids, seeing my daughter ..." She pauses. "I feel like Rip Van Winkle -- I've never even seen the Internet!" And finally, she says, "I want to get out and have a good cry. It's hard to have a good cry in here. Not only are your eyes swollen for a week but you feel like a wrung-out washcloth. And you're so vulnerable and subject to something going wrong ...."

As for Mark, he says he doesn't expect "the clouds to part and the sun to shine" the moment Amy walks out of prison. "It's going to be a huge adjustment for all of us," he says, "and Amy and I have already talked about getting some family counseling when she comes home. It's going to take a lot of work."

There's no guarantee that Amy will stay on the straight and narrow once she's out, but she insists that she will. "I know there's people who are going to say, 'Leave her in here, she's just a drug addict.' But then look at Robert Downey Jr., look at Michael Irvin, look at Roy Tarpley," she says of three celebrities who received probation for their drug offenses. "Yeah, there's people who come back, but what do they do to prepare us so we don't come back? What I say is, look, I was born with the ability to be an addict, and I took it to the extreme. Even though my dad was a drinker and I swore I'd never be a drunk, I was a drug addict instead. Even though I watched him go through struggles in AA and I didn't want to be like him -- I was worse than him. It's a behavioral thing," she says. "I want to stop the cycle." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.