Salt of the Earth

Cesar Chavez Remembered as a Man of 'La Causa'

By Paul Ciavarri, Fri., April 28, 2000

Cesar Chavez ... social activist, celebrity, Hispanic icon -- was a hero to some and a pain in the ass to others. Not everyone in Austin liked or welcomed him, but many did. Chavez's influence on Austin is remarkable, considering that Texas is a right-to-work state with no allegiance to other states supportive of the Cesar Chavezes in this world. While Chavez's efforts, in the end, may not have turned Texas into a labor-friendly state, his influences here still run deep. The farmworkers' rights activist helped serve as both a catalyst for the Chicano civil rights movement of the Sixties and Seventies, and as a role model for many local Hispanic leaders. Last year, state lawmakers passed a state holiday in his honor, which made its debut this year on March 31, Chavez's 73rd birthday. Events in his honor continued into this month in observance of the seventh anniversary of his death on April 23, 1993. I first met Chavez in college a decade ago. He had come to speak on my campus at Colgate University, and I, a shy student activist, was given the opportunity to introduce him to an audience of 700. That summer I signed on as a United Farm Workers (UFW) volunteer and went on to Chicago with volunteers from Amherst and Harvard. We crash-organized a rally for Chavez well-attended by union rank and file, radio columnist Studs Terkel, and 500 supporters and onlookers.

But back to Austin, a few decades ago. Some community activists invited Chavez to march with Hispanic workers on strike here against Economy Furniture, a manufacturing company on McNeil Road. At the time, the company's mostly Hispanic workers -- 260 of whom belonged to Upholsterers Union Local 456 -- had been walking the picket line for higher wages. The strike began in 1968 and lasted nearly three years, with most of the workers ultimately winning back their jobs.

Chavez arrived at a defining moment in Austin's labor history. Monsignor Lonnie Reyes, a longtime Chavez friend, recalls the event as "a very critical time ... one of the big concerns was just to keep the momentum going. The other [was] to keep it from getting violent."

In anticipation of the labor leader's arrival, the Texas Senate narrowly passed a resolution on Feb. 5, 1971, welcoming Chavez to Austin after three previous votes had failed. By the next month, Economy Furniture began reinstating striking union workers on the orders of a Fifth Circuit Court ruling.

Following are interviews with local activists who knew Chavez and helped shape Chavez's idealism in our Central Texas town.

Monsignor Lonnie Reyes

Pastor, St. Julia Catholic ChurchBorn and raised in nearby Lockhart, Monsignor Reyes grew up picking crops with his brothers in North and South Texas. He met Chavez after Reyes took up residence in St. Julia parish -- a frequent resting place for Chavez during his many visits to Austin. "One of [my] strongest memories of Chavez was when he came to Austin ... to help with the Economy Furniture strike. We were right at the crux of where ... workers were ... getting frustrated in their efforts to get management, to get the owners to negotiate with them. La Causa was a struggle ... that can be understood only within the context -- particularly in Texas and really in the Southwest -- of discrimination and the exploitation of workers and families. Even in my lifetime as a youngster, we couldn't just go anywhere, go into any place of business [or] restaurant because of the fact of color. So there was this very definite cry for recognition, for equality, for justice.

"[Because of Chavez] there has been a greater tolerance, if not acceptance, of Hispanics. But there are situations that remind me that things aren't as improved as I'd hoped they would be. Sometimes you look upon I-35 as a barrier, in a sense, with different attitudes on either side. Cesar did a marvelous job. He certainly started something, but it's not completed yet. What's missing now is that voice calling for justice."

Rebecca Flores Harrington

Texas state field director, AFL-CIOHarrington first met Chavez in 1970, and in 1973, she started what would become nearly two decades of working for the labor leader. Joining the movement "focused me in my career. [I was] at the University of Michigan ... the first time I ever saw him in person. [A group of us] had a tiny little chance to talk to him ... and he said, 'You know what you guys ought to do is to join up with us after you get out of school.' So some of us took him up on that.

"[Cesar] was probably the most sincere person you would ever want to meet. He was honest about himself and about what he was doing. On the other hand, he was a very demanding leader. He led the way. He was the example for us, and then he demanded that we work. When Cesar started this movement, he opened the doors to anyone and everyone. He used to tell me it was like a river, a river of people coming through, giving a month, giving two months, giving three months. In the long run, he never knew the impact that participating in the movement had on those folks. We measure ourselves in days ... but that's not really the measure of the impact that working with Cesar or with the union really has on individuals. It's a lifelong impact."

Bishop John McCarthy

Roman Catholic Diocese of AustinBishop McCarthy marks the beginning of his support of the farmworkers back to Houston, where he was serving as a parish priest when he met Chavez. "The Roman Catholic Church has long had a strong tradition of [supporting] the right and even the duty of workers to organize in order to better their economic status and to give them a voice in the world of production," McCarthy says. "Cesar Chavez symbolized hope in what was previously a very barren, difficult situation. The CBS documentary Harvest of Shame sensitized millions of Americans to the extraordinary suffering of families tied into agriculture. The irony was that the people who produced our food could not afford it. Chavez stepped in ... and gave the farmworkers the belief that their situation could improve.

"Chavez was a man so consumed with his pursuit of justice that no price was too great for him. His commitment to justice included securing it by nonviolent methods. That's why his frequent, extreme fasting was so important for the cause, and why it was so effective while he was alive. While the farmworkers' union never became the strong one that Cesar had hoped for ... the followers and supporters [of the UFW] brought about improved conditions for farmworkers and migrants in health, education, and wages."

Lupe Ramos

Bilingual teacher, Harris ElementaryRamos, who was named National Bilingual Teacher of the Year last year by the National Association for Bilingual Education, was teaching first-graders at Metz Elementary in 1987 when Cesar Chavez paid a visit to the school. She recalls that he "came [to Metz] in the morning and we all greeted him outside. We made flags and chanted ... 'Cesar Chavez' as he went by." Years later, in 1993, many of Ramos' former students from that time lobbied the Austin Independent School District to adopt a resolution supporting the grape boycott. But their proposal failed to sway the school board. "[The students said], 'Wait a minute! We went to the board and we showed them why we didn't want grapes and yet ... they're not hearing us,'" Ramos recalls.

"My answer to them was: When you grow up, you need to become a leader. You need to make your voice heard, not with violence, but with your vote [and] by getting people up there that are going to represent you. [Today] I talk to my students about the struggles that farmworkers have had ... to have better homes, better facilities, people listening to them ... and that by speaking up without violence -- that is something I always stressed -- you could get things done. My favorite saying is '°Sí, Se Puede!' [Yes, it can be done. This is a popular refrain of the UFW.] You have to also encourage them to become the leaders of tomorrow. And what better way to do it than to give them an example? 'Well, this was a good leader. He's gone, but you can continue this for the rest of us.'"

Rev. Lydia Hernandez

Executive director, Manos de CristoThe Rev. Lydia Hernandez, a former nurse, has a lifelong record of tending to the health and spiritual needs of U.S. farmworkers. "I met Cesar in 1972 when I went to the grape fast in Arizona. Cesar had sent out this letter asking people to come join him. I got there and Marshall Ganz [one of Chavez's lieutenants] asked, 'Why are you here?'

"'Well, I'm here to help.'

"'Where are you from?'

"'Gainesville, Florida.'

"'Good. You need to get up in the morning and fix breakfast for 150 people.'

"I said, 'Okay ... '

"When I finally saw Cesar, I said, 'Please don't damage yourself.' He said, 'Don't you have faith?' [she laughs] Because he did, right?"

Hernandez recalls another time when Chavez was at her home in Florida being interviewed by a crew from the St. Petersburg Times. Her son, who was five years old at the time, was so excited that Chavez was visiting their home that he burst through the door shouting, "Cesar! Cesar!"

"But my ex-husband stops him. 'Matthew, Cesar's in the middle of his press conference. You can't disturb him,' and just picks him up before he even gets to hug Cesar. Cesar sees this and says, 'Excuse me,' he tells the press people, 'one of my friends has just arrived.' He says, 'Matthew, come see me.' Oh! He gave him a big hug. 'How was your day?' And Matthew asks, 'How is Boycott [one of Chavez's dogs]? Is it big?'

"If I had a camera, that's the story I would have told," says Hernandez. "This person who just stops a press conference, sees this kid, and says, 'Well, how was your day at school?'"

Jim Ellinger

Wheatsville Food Co-opEllinger met Chavez while working for Wheatsville Food Co-op, the first grocery story in town to boycott grapes. Wheatsville still supports the grape boycott, and Chavez visited supporters there in the early Nineties. Ellinger says he paid greater attention to Chavez's cause when he got involved with Wheatsville. "I realized I had all sorts of things in common [with the cause]," he said. "Deep union roots in my family, labor organizing for the disenfranchised, and it was a food issue. Chavez was a champion [of] the men and women who literally and figuratively feed America. Americans just frequently forget why [produce] is so damn cheap in this country. It's because people work for pennies, under extraordinarily bad conditions.

"I don't know what Chavez expected Wheatsville to look like, but he was impressed. All this beautiful produce. We showed him the organic stuff, and we had a few UFW flags up. I do remember having dinner with him a couple times at Wally and Ruth's, my aunt and uncle. The image I always have of Chavez was he was tired. I can remember him scooping up his beans and tortillas in a plate. Looked like he was going to fall asleep ... "

Amalia Rodriguez-Mendoza

Travis County District ClerkAmalia Rodriguez-Mendoza was a student activist at UT in the early 1970s when she met Chavez through her participation in the Chicano movement. "I was at the time with MAYO, the Mexican American Youth Organization, considered a militant organization. The first time that I ever saw him was at the university. [There was talk of] having a demonstration going from the university to the state Capitol, to try to get legislators to meet with him. Of course, he was considered a radical at the time. Nobody gave him the courtesy. We wanted him to address the Legislature ... and nobody was open to that.

"Chavez really signified to us what social activism was all about. You could feel the passion that he had for what he was doing. That was very contagious. It got us all involved. ... What impressed me about him was his ability to organize not at a large level, but to have the presence of mind to say, 'How do we keep these people helping us, how do we keep them from getting discouraged?'"

Rodriguez-Mendoza boycotted grapes, table wines, and lettuce. "One liquor store would agree to remove the table wines and the other ones would say we should go boycott Safeway," she recalls. She and other students also took on the Texas Union when it served lettuce not picked by the UFW.

Chavez, she says, "had a vision, and you have to respect somebody who has a vision for where they're going and what it takes to ... stay the course, not to waver. So when we celebrate for the first time in history a holiday for him, that means something. When 30 years ago the Legislature wouldn't have anything to do with him."

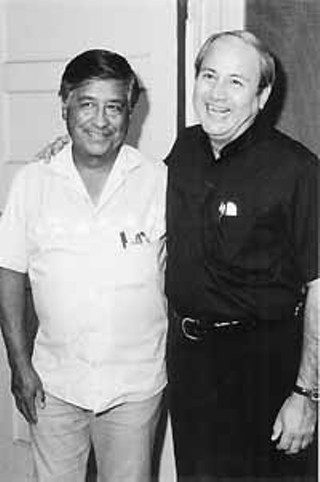

Sen. Gonzalo Barrientos

Texas state senator, D-AustinBefore winning election to the Texas House of Representatives, where he served from 1975-1985, Barrientos, a former migrant worker, served as a community organizer who got to know Chavez during his work with the UFW's grape and lettuce boycotts.

"Every year [from] when I can remember," Barrientos recalls, "we were on the migrant trail. I grew up like that until I was 18. The last year of picking cotton, I said, 'I'm not going to pick cotton anymore. I'm not going to chop it. I hate it.' [I] first heard of [Chavez] in the Sixties ... how he was working with farmworkers. [I] started thinking back ... [on] all the crap that we had to go through. That's what really led me to run for office in the first place.

"I was helping with the huelgistas [strikers] and we brought in Cesar Chavez [to the Economy Furniture strike] to help us motivate the people -- not just the workers, but the city in general [and] the university. And after [people] met him, how cool he was, how gentle, 'Hey! Who's afraid of this guy? What's he going to do to people?' Nothing but [raise] hell.

"We [the State Legislature] did receive Chavez. When I first got elected, 1975, we received him right here, for a press conference, in the Speaker's committee room. We had a big banner stretched out, had the black hawk [the UFW flag], and some of my colleagues [were] very disturbed about that, talking about 'that Communist' ... to the point where I got in one of those people's faces and said, 'Look, this is the people's house. That's not a communist insignia. That is an insignia of hope for poor people and farmworkers, but even if it was a communist insignia, the Constitution of our country guarantees you that we can express that.'

"[Chavez worked] by showing the ideal ... in a very gentle, but affirmative way, so that people start saying, 'Yeah, yeah, that's right! What really matters is human beings living right, raising their children, loving each other and not beating the hell out of each other, or trying to screw each other out of the almighty dollar. You're right! That's what really counts. People.'" ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.