True Believer

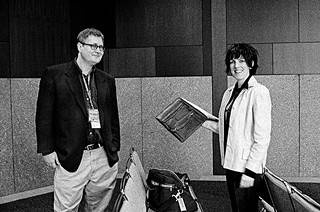

Brent Grulke, the heart of SXSW

By Michael Corcoran, Fri., March 15, 2013

"It either makes sense for you to be at South by Southwest or it doesn't."

That's what Brent Grulke used to say when asked what kinds of acts were meant for the world's largest music festival.

And yet, one of the bookings SXSW Creative Director Grulke worked hardest to put together seemed completely illogical at the time. Why would Tom Waits, iconic songwriting genius, want to come to Austin and play for free in a 1,100-capacity venue? This was before appearances by music's biggest names – this year Green Day, Depeche Mode, Prince, and the guy who turned the "Harlem Shake" into a techno "Macarena" – became routine.

Not only did it make little sense for this folk hero, who almost never performed live, to play a festival of baby bands, but the offer from his manager came just two weeks before the 1999 session.

SXSW Executive Director Roland Swenson, the pragmatist, worried about adding extra work to an already exhausted staff and huge production expenses. Waits wanted to play an old theatre, and the Paramount was already scheduled for SXSW Film screenings.

"I was skeptical," recalls Swenson, "but Brent would not be dissuaded."

Anyone who knew Brent Grulke, who oversaw booking the Music Fest from 1994 until his unexpected passing on August 13, 2012, at age 51, can imagine him trying to convince Swenson that Tom FUCKING Waits would be worth whatever it took. Grulke's memory lingers in any excited stutter where the mouth can't handle everything being telegraphed from the brain. SXSW staffers will tell you they still have conversations with Grulke – still feel him coming into the room with a big smile on his face when something big goes right.

"You don't become a music fan and start a festival so you can say 'no' to Tom Waits!" they hear him saying, in a voice that never really left Nebraska.

"He was so passionate," remembers Swenson. "So I said, 'Okay, make it happen. But if it doesn't, it's your ass.'"

Fourteen years later, we're still talking about that show, wherein SXSW turned the corner from regional to international. Demand for tickets was so high that one die-hard fan gained entry during the day by dressing as a maid and was found hiding in a closet just before showtime.

For once, Grulke and Swenson turned off their radios and took their seats in an opera box overlooking the stage. Grulke had an extra ticket, so he gave it to the faux cleaning lady because he knew what it was like to love music so much you'll do anything to hear the best of it.

The trio, just three fans for two hours, must have jumped a little in their seats when Waits pulled out "(Looking for) the Heart of Saturday Night." Written about small-town boredom and desires – the opposite of SXSW – the tune remains a theme of this week that mixes big business with untold discovery. Saturday at midnight beats the heart of SXSW hardest. It's when we suddenly want more after so much whining about having had way too much.

Consider Brent Grulke SXSW's ambassador of more. When he took charge of booking the music in 1994, there were 482 acts. Within five years that total doubled. Last year, more than 2,200 acts – almost a third from outside the U.S. – played official SXSW showcases on 105 stages. More music, more music, more music. That was mostly the doing of Grulke, who traveled around the world in the off-season – to Korea, Chile, France – to get more countries to feel that SXSW was where you showed the world your indigenous musical charm.

How Will the Wolf Survive?

"Playing music is a noble calling" was always Brent Grulke's creed. The worst part of his job was rejecting 80% of the acts who had applied to the Conference. That's another reason he found a way for 2,000 to perform.

With the start of every new year, SXSW becomes a stress factory for decision makers. Grulke met it head-on with a goofy laugh, even in early March. His easygoing personality helped make SXSW a friendly, music-first type of industry juggernaut.

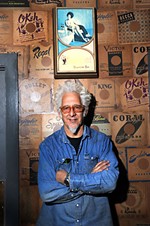

"He had an inner gyroscope that kept him centered," says Louis Black, the SXSW co-founder who was Grulke's T.A. at the University of Texas in the early Eighties, then his editor at The Austin Chronicle when Grulke put his passion for music into words. Unflappable, egoless, handsome, and nerdy – that was Brent. Austin had a big crush on him.

"He wasn't an ordinary person in any way," Black continues. "Brent was an extraordinary person in every way."

He had crazy eyes when he got excited, which was the basis for the tattoo he received from Mike Malone in 1986, the symbol used at GrulkeFest in September.

"That kid," Malone said on meeting Grulke, "has the eyes of a horse in a burning barn."

He was a fan, first and foremost. A fan of good food and wine. A fan of women and long conversations. Someone who sought out the best in life, especially music.

"When I'd just barely met him and we really didn't know each other, he made me feel like he admired me and was on my side," recalls Britt Daniel of Spoon, who was forced to get a day job in 1997 after his band was dropped by Elektra, and whose new band Divine Fits dots this year's SX schedule. "That meant a lot."

So many bands and writers can say the same.

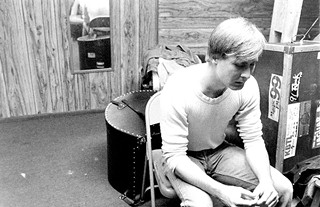

Many of us ended up where we are today because we heard some songs on the radio when we were kids. We wanted to be in the middle of that magic, even if the guitar strings hurt our fingers, so we looked for other ways. Grulke, who nurtured a lifelong love affair with records, made his mark initially as a soundman, road manager, and the co-producer of 1985's Bands on the Block compilation. He liked music loud and mixed sound accordingly.

All of a sudden there were all these bands. That's how the scene started in the mid-Eighties, with Austin groups like True Believers, the Reivers, Big Boys, Glass Eye, and the Offenders showing that Austin wasn't simply the providence of white blues bands and long-haired country. The cool thing about the Austin of that time was that people who went to see Wild Seeds and Doctors' Mob also went to hardcore punk shows and the Neville Brothers at Liberty Lunch and, of course, Willie Nelson. Grulke went out on the road with most of the so-called "New Sincerity" bands (the Troobs, the Reivers, Wild Seeds, Doctors' Mob), but also crossed the country with reggae band the Killer Bees.

Wanna test your passion for music? Go on tour in a van with a marginally known band. Driving for hundreds of miles a day, dealing with a cranky bar staff upon arrival, sleeping six to a room – when there's actually money for a motel – and loading and unloading, loading and unloading. Believe me, most of us would cry mommy within days.

"I'd never done it to make money," Grulke told the Geek Weekly fanzine in 2001, almost a decade after he'd retired from the road. "I'd done it with my friends, and that was the fun of it."

Everyone was figuring it out, eking out a living playing music.

"Bands didn't know how to go about getting recorded and going out on the road, and Brent helped with that," says the Wild Seeds' Michael Hall, now a writer for Texas Monthly. "Besides having great taste in music, Brent knew technical things, like how to set up a P.A."

With Grulke, you not only got a soundman and roadie, you got a musical conscience.

"He was like our younger big brother," says Hall, "always pushing us on writing, touring, recording."

Too many musicians don't have someone like that, whom they can trust. When the True Believers completely kicked ass, Grulke was there with the kudos, full of faith and belief in a band so full of doubt.

"He helped us stay together," says the group's frontman, Alejandro Escovedo. "He'd say, 'You guys are great. You've gotta just keep going.'"

I lived with Brent and a bunch of other guys in a big house on West 30th in 1987, the year SXSW started. There was absolutely no money for anybody, so Grulke volunteered as stage manager at the Continental Club that first year, when some 172 acts played 15 venues. Wristbands were $10 and didn't sell out.

He married Kathy McCarty of Glass Eye and they ran production for the growing Festival the next couple years. Grulke was also the Chronicle music editor during that time. When the marriage broke up, he moved to L.A., eventually returning to Austin in 1993 and organizing panels for SXSW. Once co-founder Louis Meyers left, Grulke was Swenson's only choice to replace him.

It either makes sense for you to be at SXSW or it doesn't.

"South by Southwest was the ideal job for Brent," says Hall. "It translated his passion for music. Brent had this way of going on about a band. He loved Los Lobos and he'd say, 'This is the best band in the world,' and he'd find ways to talk about them that would never get boring."

Now he was in charge of finding the next Los Lobos.

Things didn't happen overnight for Brent Grulke. He dedicated his life to supporting those whose music he admired. It was never about money, except that when he started making some it allowed him to buy more records, more guitars. He did hard time in the trenches for over 10 years before he got the dream job, which wasn't one when he got it.

That first SXSW there were 700 registrants. This year, just the music portion of the Fest will have over 19,000 badge holders. Those coming to SXSW to make it big are missing the point. Look at the slow, steadily rising trajectory of Grulke's career. First you learn to become a professional, and then you never stop.

You live it like you're going to die.

I Second That Emotion

People get married and try to stay that way because it's easier to make big decisions. Should we buy a house or rent? Fix the car or buy a new one? You need a sounding board. Grulke and Swenson were that for each other.

"[Because of the pressures of SXSW] you bond with people in a way that's unique," asserts Swenson. "We were always on the same page."

Asked to recall a disagreement, Swenson laughs.

"We used to have this procedure of stuffing the wristbands for each band into envelopes," he explains. "It would take all night, so the music staff would get beer and pizza. I'd come in the next morning and the office would be a wreck. So I said, 'That's it, we've gotta find a new system.'

"Brent fought me, but I won that one. Then I realized what he really loved was the party."

Both men were on a mission to preserve the integrity of their Conference even if it meant occasionally taking a public relations hit. Grulke became the enemy of comments sections after he declared in an interview that SXSW was designed as an event for the music industry, not the general public. This was in answer to all the townie bellyachers who complained they couldn't get in to see Smokey Robinson or Sonic Youth or some other favorite act. They didn't understand that the bands were playing for free, virtually, so that the music industry – club owners, agents, managers, writers, record labels, soundtrack supervisors, TV bookers, etc. – could see them perform and perhaps help their careers. Smokey Robinson doesn't care if the desperate housewives of Hyde Park can't get their "Tears/Clown" on.

Grulke and Swenson were almost telepathically aware of what was best for SXSW, so if one disagreed with the other and demonstrated more passion in his stance, that's usually the way it went. Meeting with Swenson at his office at the SXSW headquarters Downtown takes on the distinct feeling of sitting with a man who's lost his spouse.

"Brent used to keep me apprised of everything," he says. "He instinctively knew what I would want to know. And this year, I'm not finding out about stuff until later."

It's hard on him. It's hard on everybody.

"I relive these late-night arguments I used to have with him," says Julia Ervin, who worked closely with Grulke on the Music Fest for several years and is now an aide to Special Events Director Darin Klein. "We would just scream at each other, partly as a way to handle the stress."

She misses that passion. Just minutes earlier, Ervin received a disappointing email and thought, "Brent's gonna shit." It's like he's still there.

There's "a deep hole, a big space to fill," says Escovedo, whose True Believers decided to reunite after blowing the doors off the Moody Theater at September's GrulkeFest (see "One Big Guitar," Feb. 22). The tribute raised $75,000 for a college fund set up for Brent's six-year-old son, Graham. "It doesn't even seem like SXSW [this year]. He was SXSW, the best part of it."

The spirit of this annual 10-day blowout came in large part from Grulke's huge appetite for what he knew, but especially for what he didn't know.

"Brent had a way of pulling you into his world," says Black. "There was almost nothing Brent was afraid to do."

Life is a feast. You can nibble away until you're too old to taste anything or devour the goodness with gusto and hope for the best.

Last July, in the midst of the Olympics, Grulke and Swenson were invited by the British government to attend a symposium of international movers and shakers in an opulent building on the Buckingham Palace complex. There's the guy who wrote Downton Abbey, and over here fashion designer Stella McCartney. Howard Stringer, then chairman of the board of Sony, spoke as Champagne was served. Grulke and Swenson met in the Eighties when they had to check under seat cushions for money to buy a cheeseburger, and here they were in a room with other arts industry elite.

"Yeah," Swenson whispered to his closest business confidant. "This is okay."

A laugh came in reply. Those who knew Brent Grulke remember it well.