The Girl Who Met Robert Johnson

Shirley Ratisseau, living history

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Aug. 3, 2012

Memory and history. Both have a way of being skewed by, and into, context, especially when delivered orally. Oral history has been overwhelmed by Internet history, and it's easy to get lost in cyberspace.

Ask Shirley Ratisseau, 82, in failing health with heart problems, living in California, and wanting to move home to Texas.

"Texas doesn't want me!" she cries.

It probably feels true to Shirley, but it's not. Shirley Ratisseau is more than living Texas music history with eye-popping stories to tell. She blazed trails by blurring the distinctions between black and white music communities, and not just in Austin, but everywhere she lived.

"Shirley was the first white lady blues singer I knew, maybe the first in Austin," recalls local blues great W.C. Clark, powerful affirmation of Ratisseau's almost unbelievable life.

She crossed paths with Duke Ellington, the Rolling Stones, T-Bone Walker, Mance Lipscomb, Billy Eckstine, Albert Collins, Count Basie, and countless blues and jazz legends. Her family was built out of tragedy and flouted racial mores of the day on the South Texas coast. Her sage experience in the early Seventies led her to a teenage guitarist named Stevie Vaughan, whom she recorded and mentored.

Even so, her name has slipped through time's back pages.

"If Shirley says so, it's true," states W.C. Clark unequivocally.

That the venerated guitarist adds no questionable ifs, expository ands, or qualifying buts to his statement echoes corroborations by Austin author Joe Nick Patoski (Willie Nelson: An Epic Life), Texas Music Office director Casey Monahan, and numerous blues musicians. That's important because memory can be tricky, and among the buried treasures of Shirley Ratisseau resides a bit of history to send music scholars scrambling to their computers.

When she was a little girl, Shirley Ratisseau met Robert Johnson.

Kind Hearted Woman Blues

Mississippi-born Robert Johnson (1911-1938) remains a touchstone for the blues, a call to arms for Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones, among many other British Invasion acts who discovered his handful of recordings through Columbia Records' landmark collections. Only two known photos of the guitarist exist to illustrate a grand total of 29 songs.

On the way to Shirley's tale of a 30th song, understand what it meant to be a Ratisseau. Look no further than the Galveston hurricane of 1900, a natural disaster that wiped out one-fifth of the island's population overnight. The Ratisseaus lost more family members than any other; according to lore, more than 200 in all. George Ratisseau – Shirley's father, age 12 at the time – survived only because he'd ventured downtown with the laundry and was stranded there when a wall of water and wailing winds wiped out most of his family.

Ratisseau resilience extended also to mother Thelma. When Shirley's arrival into the world appeared imminent, her grandmother and aunt couldn't get Thelma to the hospital until a young black man in a truck offered to transport the three white women. They arrived in the nick of time – Shirley was born on the lobby floor to an audience – but in their haste, they left their purses and suitcases in the truck.

"Shirley, you were born to great applause," recalled the driver years later.

Aaron Walker had waited through the birth to return the women's belongings. As T-Bone Walker, he went on to electrify the blues on six strings, primarily playing Texas and the Gulf Coast. The bars and clubs around Houston in the early Thirties were linchpins in the development of blues, and George Ratisseau owned two, the Barn and the Cave.

"Many of the young guys who worked there became well-known musicians," writes Shirley in an email. "My dad said he spent many times getting Lightnin' Hopkins' guitar out of hock so he could keep the boy's mind on washing dishes or whatever his job was."

When Shirley was 5, the Ratisseaus weathered the Depression summer in a tent near Rockport, Texas. They owned the Jolly Roger Hunting and Fishing Club. Nothing out of the ordinary, but it was known as a place where blacks could frequent and vacation. Musicians, too, since Rockport was a Gulf Coast town accessible from both Houston and San Antonio.

"I thought he was just a boy, so I took him fishing on the pier," recalls Shirley more than 75 years later. "Johnson and I wrote a song about it. The words only exist because my mother wrote them down. She said later, 'That boy insisted I write down the words! Who was that boy? He was so ill.' And my mother never did realize who he was, but she wouldn't have known B flat from C sharp, either.

"In my memory, it was fall; my mother was getting Thanksgiving together. He sat at the table, but was so sick he nearly fainted. He jumped up and ran to the door. He'd never sat at the table with a white family. My mother said, 'I've got to feed you, you're very sick. And I'm going to put you to bed.'"

The life of Robert Johnson is among the most mythologized in all of music. From his largely undocumented 27 years springs rock & roll's infamous supposition of selling one's soul to the devil for musical stardom. What is known is that during that same year Ratisseau cites, 1936 – in November – Johnson made his best-known recordings in San Antonio at the Gunter Hotel. The following June in Dallas, he completed a second batch. Also cataloged from this period is that Johnson was arrested in San Antonio for vagrancy and beaten. Don Law, who produced the Gunter Hotel sessions, sprang him from jail and rented a room in a boarding house for him while the songs were recorded.

What did Robert Johnson do between November 1936 and June 1937?

Shirley's account of meeting a young musician her family described as "ill," "sickly" – one in a state of physical disrepair as though he'd been roughed up – is beyond tantalizing. Given the Ratisseaus' reputation for tolerance and welcome at the Jolly Roger camp, it's entirely possible Johnson got advice that a few hours south of San Antonio on the coast, he could rest and recuperate. And fish.

During the Depression, fishing was eating. To eat was to live.

I Say Me for a Parable

Born to applause, life and music are synonymous to Shirley Ratisseau. In fact, T-Bone Walker brought her onstage in Houston when she was 11. She met guitar great Albert Collins at "about 12, 13, or 14, when we would run down the block on West Gray Street to the Bar-B-Que Stand and play and sing for nickels, dimes, and quarters." His was another enduring friendship. In Austin at Antone's, "The Ice Man" would often mutter, "Where Shirley?" into the microphone.

In one Gulf Coast band, she subbed for a girl singer who'd left to try her hand at singing in Hollywood Westerns (and had some luck after changing her name to Dale Evans). Singing made it into Ratisseau's formal education as well; she was inducted into the national honorary band sorority Tau Beta Sigma at Texas Tech University in 1947. At college, she married saxophonist Mickie Sweeney, which opened a new chapter for the young singer.

That's where Shirley Denise Ratisseau starts slipping between the cracks, actually. On the East Coast in the late Forties, her last name was Sweeney. When she married a second time the following decade, she used her married name, Dimmick, professionally and in bylines is often quoted as such. Googling any of her names offers little return, but what does appear is enticing.

Detailing Navasota bluesman Mance Lipscomb's autobiography I Say Me for a Parable, author/compiler Glen Alyn documented the friendship between Shirley Dimmick and Lipscomb.

"In 1951, Shirley was in New York, talking to one of the members of Count Basie's orchestra. After learning she'd spent time in Texas, he told her if she really wanted to hear what the blues was all about, go listen to a guy named Mance Lipscomb. She could find him in Navasota. She surely did. On several occasions, all before Mance packed up and moved to Houston."

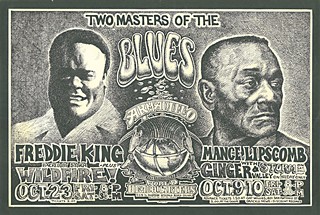

More than two decades later, booked for Armadillo gigs with Freddie King in 1975, Mance Lipscomb slept on the couch at Shirley's house.

"Even then, it wasn't accepted for a black man to stay over at a white woman's house," sighs Shirley on the telephone.