The Greatest Gift

When Scratch Acid scorched the earth, an oral history

By Greg Beets, Fri., Sept. 1, 2006

The afternoon high tops 100 for the umpteenth straight day. Lawns are tinderbox brown. Traffic is at a standstill. Nerves fray; minds curdle.

It's a beautiful day for a Scratch Acid reunion.

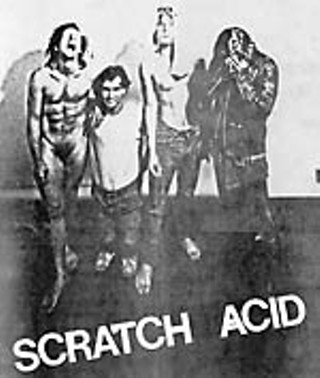

From 1982 to 1987, Austin's Scratch Acid roared with unrestrained ferocity while landing their kicks with precision. Between vocalist David Yow's theatre of confrontation, Brett Bradford's jagged guitar spirals, and the rhythmic lockdown of bassist David Wm. Sims and drummer Rey Washam, the quartet created a monstrous, lashing sound that influenced bands long after their breakup.

Scratch Acid's most direct descendant was the Jesus Lizard, formed in Chicago by Yow and Sims with guitarist Duane Denison and drummer Mac McNeilly. The Jesus Lizard parlayed their springboard from Scratch Acid's sound into a major label deal and a Lollapalooza slot in 1995. Scratch Acid also counted many of Seattle's prime movers among their most ardent fans, including Soundgarden's Kim Thayil and Nirvana's Kurt Cobain, the latter of whom once listed the band's 1984 debut at No. 7 in a Top 50 ranking of favorite albums in his journal.

Yet even if they hadn't been the link between Nick Cave's Birthday Party and Sub Pop, Scratch Acid remains one of the quintessential Austin punk rock bands, literally throwing themselves into performances and generating enough mad fever to blow up a blast furnace. Austin has changed a lot in two wild and wooly decades, but on a late summer afternoon, Scratch Acid still makes perfect visceral sense.

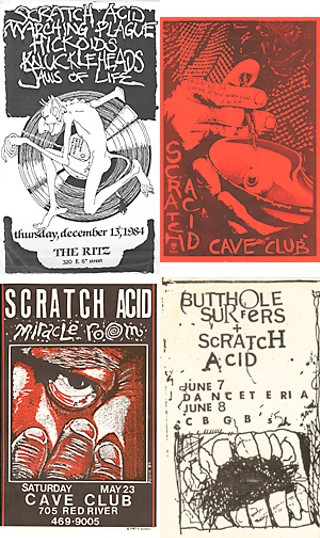

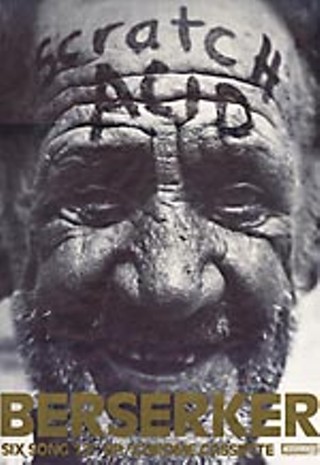

The band played just 146 shows in their five-year run. Their initial EP and sole full-length, 1986's Just Keep Eating, were released on a plucky local label called Rabid Cat. A final EP, Berserker, appeared on Touch & Go in 1987.

Having turned down reunion opportunities in the past, Scratch Acid agreed to play Touch & Go's 25th anniversary celebration in Chicago September 9 as a gesture of gratitude toward T&G head Corey Rusk. With that booked, an Austin gig was only natural. Given how much Scratch Acid informed the musical groundswell that birthed Emo's, having them play the club's 14th anniversary is a particularly rich stroke of kismet.

So how did a bunch of twentysomething punks (save for Sims, who was only 19) become progenitors of a musical movement? The saga begins as the Eighties dawn, Austin's population is about 350,000, a few hundred of whom have kick-started a vibrant punk rock scene in the wake of the headline-grabbing 1978 riot at Raul's, instigated by Huns singer Phil Tolstead's punk-on-cop kiss. One person influenced by those headlines was David Yow, well-traveled son of an Air Force fighter pilot and recent high school graduate.

David Yow: One Halloween, a friend of mine and I went to Raul's to see the Huns play. We'd read in Rolling Stone about the time the police showed up. That completely changed the way that I thought music should be presented.

Brett Bradford: Austin was a city with a small-town atmosphere. For some reason, the underground music scene just took hold and exploded. That whole "go start your own band!" thing was for real.

David Wm. Sims: I went to Austin High. I probably went toward being in a band to get away from the high school experience.

BB: I moved from Dallas in the fall of 1980 and put up a poster at Inner Sanctum Records saying "guitarist looking for band." There was this guy behind me who said, "Oh, we're looking for a guitarist." I turned around and saw this crazy looking guy with blue hair. It turned out to be Chris Wing of Sharon Tate's Baby. I started playing with him and then we picked Rey up as the drummer.

Rey Washam: The suburbs of Dallas were very uncultured and stale and safe and white. When I moved from there to Austin, a whole other world opened up to me. I started going to UT and met some friends there who knew a lot more about music. They turned me on to the Ramones, and it just went on from there.

Chris Wing, Sharon Tate's Baby/Jerryskids vocalist: We did tons of acid. Austin had a great flood on Memorial Day 1981. We were practicing and trying to think of a new name. Brett said, "Let's be Jerryskids." We were weak in spirit, so we said okay. Then we stopped practice and said, "Let's go out and save lives." That's what we did. We actually did save a couple of lives during that flood. We would come across scenes of disaster and pull people out of stranded cars with torrents of water washing down around 51st and Guadalupe where the creek rises. We were all tripping like madmen.

DY: It didn't occur to me to be in a band, but with the whole do-it-yourselfness of punk rock, I thought, "Shit, I'll play drums or bass or something." Next thing you know, I was playing bass in a punk rock band called Toxic Shock. We did Ramones/Sex Pistols kind of punk rock. Nothing too thought out. We were making posters for it way before we had the band.

Steve Anderson, Toxic Shock vocalist: We played a couple of times together, then I split the band. The Butthole Surfers opened for us at our first show. Everybody showed up to see this poster band play at Club Foot. We were being spat upon and beer was being thrown on us. There was a mezzanine around the stage and people were throwing trash down on us. They'd been waiting for a year to fuck with us.

DWS: David and I were roommates. We had a house at 51st Street and Avenue H. That was where we lived when Scratch Acid started. Jerryskids had broken up and I think Brett and Rey invited David to play bass in a band they were starting. I just kind of made a pest of myself by showing up and acting like I was in the band until I was.

While Scratch Acid began rehearsing in 1982 as a quintet with Toxic Shock's Steve Anderson on vocals, David Yow on bass, and David Wm. Sims on second guitar, the California hardcore of Black Flag and the Circle Jerks was the underground sound du jour. Having embraced the weirder, artier sounds of groups like Public Image and the Birthday Party, the new band eschews the loud, fast rules of hardcore as everything they don't want to be.

DWS: The big compliment among those bands was, "You guys are really tight." Being innovative and weird had taken a back seat.

RW: We all just started hanging out, listening to music and drinking beer. David [Yow] would make these fliers with his weird art and we'd put them up.

DY: At the time, so many Texas bands were not only cool to listen to but really, really cool to watch: The Dicks, the Big Boys, the Butthole Surfers. There were a lot of them, but those three in particular.

BB: To me, the Big Boys and the Butthole Surfers were like going to church. It was a religious, spiritual experience for me.

DWS: We made long lists of two-word combinations and settled on Scratch Acid. We wanted something evocative but nonspecific, something that indicated an atmosphere but wasn't bogged down with wordplay or specific allusions.

BB: We wanted to be our own favorite band. That was stated, and it came to be.

Scratch Acid played its first show at Studio 29 on Jan. 20, 1983. The band only performed three instrumentals because they dismissed Anderson by booking the show without telling him. "The decision they made was the right decision," says Anderson, who remains friends with the band. By the time Scratch Acid made its proper debut on March 10, 1983 at the Skyline Club, Sims was on bass and Yow was the frontman.

DWS: The bill was TSOL, the Big Boys, the Butthole Surfers, and Scratch Acid. We made $20.

BB: Somebody had passed out 100 half-hits of acid to anybody who wanted it. So there were a lot of big eyes. It was pretty interesting. I'm not advocating that, but everybody seemed to have a good time.

DY: I was throwing up all day. I was terrified. But I think it was fun. I always got nervous before shows. It would usually go away about three or four seconds into the first song. I really liked the music in the band, so I could kind of get lost in it. That helped a lot. That and drinky-poos.

Shortly after this show, Washam left Scratch Acid to replace drummer Fred Schultz in the Big Boys. Washam's replacement was Rich Malley, future drummer for Happy Family and the Horsies. The switch didn't take, and the band went on hiatus until Washam rejoined at the end of 1983. When the True Believers briefly enlisted Washam a couple of years later, he split his time between the two bands.

Rich Malley: We practiced for a month, and then we did a month of shows, and it all fell apart. There was so much chaos between Brett and David Sims. They were sort of perpetually at odds because David was totally together and Brett was totally not. David Yow was sort of in the middle. When you have a drummer like Rey Washam, he can bring a whole structure to that. I think that's what made them so great.

DWS: We played five shows in that time, and then Brett moved back to Dallas. Rey rejoined, Brett came back to Austin, and we started playing shows again in January, 1984.

RW: I'm really glad those guys didn't get rid of me when I joined other bands. I wouldn't have blamed them if they did.

In July, 1984, Scratch Acid entered Austin's Earth & Sky Studio to record their eight-song debut. Between the sledgehammer surf psychosis of "Greatest Gift," high-desert horror of "El Espectro," and the eerie string arrangement that drives "Owner's Lament," Scratch Acid remains the band's most potent recorded distillation.

Stacey Cloud, Rabid Cat Records: Laura Croteau had started Rabid Cat by signing the Offenders, and when I came on, we wanted to do a record with Scratch Acid.

RW: I remember when we first went in to track that record at Earth & Sky. We played live and went back to listen to it and I was like, "Fuck, man! Is that how we sound? That's pretty interesting!" I'd never really heard David sing because we usually practiced with a shitty PA, but when I heard him track that first song, I was like, "Goddamn, that's pretty cool!" We all looked at each other with these big shit-eating grins and started laughing.

BB: I wrote "Owner's Lament" and thought it would be cool with strings. David Sims' girlfriend at the time played viola, and we got some other people from the UT music department. Rey wrote out a string section. I'd always loved cello, and there was a part where I had a guitar solo, so I asked the cellist if he could come up with a solo to go in the solo. He listened to it once and then ran the track. What's on there is what came out of his head, totally improvised and on the spot.

DY: Once this reunion looked like it was coming to fruition, I started listening to the records. I hadn't listened to them in years. I think that first record is pretty good. There's a lot of stuff on Just Keep Eating that's pretty good, but overall it sounds like poop. With Berserker, it had been so long since I'd listened to it that I could separate myself and really listen objectively, as if I had nothing to do with it. I think that record is really, really good. I remember we really labored writing those songs.

DWS: Other than trying to go on tour, we left the promotion to Rabid Cat. I don't think we were astute enough to realize how important it was to promote a record. But Rabid Cat did what they could.

SC: It was kind of like being blind and walking through a forest. We were just taking one day at a time, and hindsight is 20/20. You can't blame them for wanting to go to Touch & Go because, hell, I would. That was the label of the time to be on.

DWS: I think Stacey and Laura's hearts were in the right place, but they were kind of making it up as they went along. It got very tense for awhile, which was unfortunate. We all underestimated how difficult and daunting it can be to keep the business correct.

Although Scratch Acid was Sims' first band and Yow's first turn as lead singer, the group quickly developed a riveting performance aesthetic. As the EP made its way around the country via fanzines, college radio, and word-of-mouth, the band mounted short tours to the Midwest and the East Coast. In 1986, they opened for Public Image Ltd., illustrating the pitfalls of meeting your idols.

RM: Sims was just rock solid. He didn't move very much. He never smiled. Rey was totally intense on the drums, holding everything together. Then you had Yow and Brett, who were completely crazed. Yow was unbelievable. You'd go and marvel at how he could give up his body with so little regard for his physical well being. Brett was playing these crazy-ass parts, and you never knew if what he was doing was intentional or not, but it sounded really good.

DWS: There were two shows that we played on consecutive weekends. David hadn't shaved or cut his hair in awhile, and he did this Jesus getup and played part of the show on a cross he built. The next weekend, he cut his hair and shaved almost all the facial hair off and did the show as Hitler. He had the brown shirt and armband. Some people weren't happy about it.

DY: The Ramones played the Back Room one night when we played at the Cave Club. I was backstage after finishing our set and there was a tap on my shoulder. I turned around and it was Joey Ramone. He said, "Nice show, David." I tried to keep my cool and act like it was no big deal. I said, "Oh, thanks a lot, Joey. How was your show?"

DWS: We played at a place called Muggins in Indianapolis, opening for the Beatles cover band that played there every Thursday night. David put a bag of flour, water, and food coloring in his pants and started flinging it around, telling the crowd he had crapped his pants.

DY: When we opened for Public Image at the City Coliseum, they had a nice spread backstage, and I went to go get a beer. Some English guy says, "Oh, you can't have none 'ah that." I said, "We're in the opening band," and he said, "You have to talk to the promo'tuh." So I asked the promoter if we could have some beer and he said I'd have to talk to the band. John Lydon was standing around, so I thought, "I'll go ask Johnny Rotten. He'll let me have a beer." I go up to him and say, "Hey, do you think we could-" and before I could even finish my sentence, he goes, "No-ahh!" and walks away. One of the guys in the band saw this going on and brought us some beer. That was really nice, but while Public Image was playing, we took all their beer, all their booze, and all their yummy food items, stuck 'em in our van and drove away.

Scratch Acid's final months were packed with higher highs and lower lows. Touch & Go released Berserker, and the band embarked on its most ambitious tour, venturing to Europe and the West Coast. They enjoyed a particularly warm reception in Seattle, where legend has a young Kurt Cobain being denied entry to their sold-out show. Despite the recognition, the quartet grew more frustrated with their career trajectory, as well as each other. The frustration finally boiled over one night in Minneapolis.

DY: The venue we played in Seattle was crazy sold out. People who couldn't get in were pressed up against the wall outside trying to listen. Those inside were spilling onto the stage. It was cram-packed, crazy, and really fun. I think a lot of the bands that got really big and popular were into Scratch Acid. There was a guy having problems getting in. I went outside and someone said, "Hey this guy is having trouble getting in. Can you put him on the list?" I said sure. It ended up being Mark Arm from Mudhoney.

BB: That last tour, where we were out for three or four months, made everyone tired and irritable.

Scratch Acid, 2006, pre-reunion rehearsal (bottom, l-r): Bradford, Yow, Sims, and Washam. Photo courtesy of Brett Bradford

RW: When we went to Europe in 1986, we spent Christmas Eve playing to one bartender and one drunk person at the bar.

DWS: Rey and Brett had a big fight on stage in Minneapolis and Rey left the band at the end of the tour.

BB: Rey and I had a blowout. I wouldn't call it a fight. There were no fisticuffs or anything like that, but we had a disagreement. I'd been drinking a little too much before the show. I didn't feel that I was messing up, but he didn't like that I was drunk.

RW: I still loved Brett and I always will, but you work with someone that closely and it's really hard. You let egos get in the way. I started letting my expectations take control. I wanted Brett to be this certain type of person and certain type of musician. I was asking him to be something he wasn't. It was stupid ego bullshit and it blew up on stage one night.

DY: I think we only had a few more shows. We got home, played one more show in Austin, and that was it.

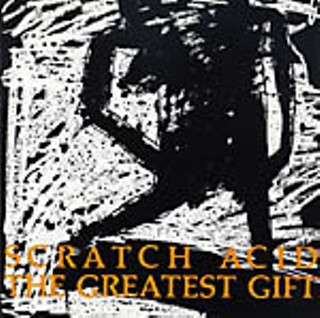

Scratch Acid's last show was on May 5, 1987 at Austin's Cave Club, but that wasn't it. In 1991, Touch & Go released The Greatest Gift, a compilation of most everything the band recorded. Whenever Scratch Acid is cited as an influence, The Greatest Gift is there to provide inquiring minds with the evidence.

By 1988, Sims, Yow, and Washam were living in Chicago, where Washam and Sims formed Rapeman with Big Black guitarist/vocalist Steve Albini. When Rapeman disbanded in 1989, Sims reunited with Yow in the Jesus Lizard and played together for another 10 years. Today, Sims, 42, is an accountant in New York City while Yow, 46, is a commercial photo retoucher in Los Angeles.

While Sims confines his musical aspirations to his home studio these days, Yow stays peripherally active in L.A. "There's a new band Juan [Monasterio] from Brainiac and Todd [Philips] from Bullet Lavolta have called Model Actress, and I sang a song on their record," he says. "I'm doing a couple of songs with the Melvins in October, too."

After Rapeman, Washam played drums with Ministry, Lard, and the Didjits, among others. He also played in Euripides Pants, an Austin swing quintet that was a scene mainstay in the mid-Nineties. Washam, 45, now lives in Los Angeles. He's the only Scratch Acid member who considers music his occupation.

"I came out here because I wanted to work hard at it," he says. "I wanted to try and bring in an income doing something that I love and that I've been doing for 30 years. It's hard, though. Some of the greatest players in the world are out here. I did a teeny bit of studio work, and I'm trying to start a band from scratch. I'm staying busy. I'm not doing exactly what I want to, but I'm happy."

Bradford, 46, still lives in Austin, just around the corner from the house where Big Boys vocalist Randy "Biscuit" Turner lived prior to his untimely death last year. When he's not working as a landscaper or bow hunting, Bradford continues to make delightfully harrowing noise with Insect Sex Act.

"Every time I think about Scratch Acid, it's like, 'Wow, how did that happen?'" he muses. "We wanted to be our own favorite band, and we turned out to be some other peoples' favorite band, too.

"So it's a happy ending." ![]()

Scratch Acid returns from the annals of music history to play Emo's, Saturday, Sept. 2.