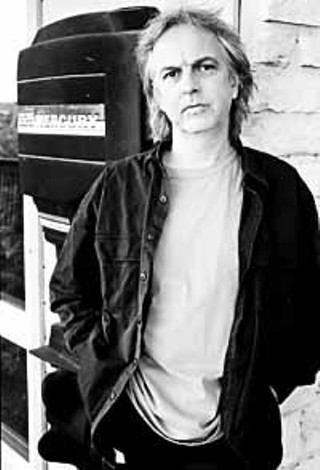

I Come From the Water

20 Questions with Gurf Morlix

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Feb. 8, 2002

Onomatopoeia. It's a good, funny word learned in high school English, a term meaning "sounds like what it is."

Morlix is the onomatopoeic surname of the noted local guitarist whose first name is equally unusual, Gurf. It's Welsh, "from way back," he allows, and the first of many quirks about the man and his music. The veteran musician's second solo album, Fishin' in the Muddy, on Chicago-based micro indie Catamount, is as good a hunkered groove as his first for the label, 2000's The Toad of Titicaca. Maybe better since Morlix is still growing into his songwriter's skin.

Songwriting is only the most recent of his accomplishments given that Morlix is a prized sideman and session player, working with the likes of Jerry Lee Lewis, Lucinda Williams, Buddy & Julie Miller, and Michael Penn. As a producer, he's overseen albums by Williams, Ray Wylie Hubbard, and Slaid Cleaves to name only three.

Morlix drove in from his Lake Travis abode to talk about his career, recording, and producing. And why he keeps going back to the water.

Austin Chronicle: How did you get so Southern-fried? You grew up outside Buffalo, New York.

Gurf Morlix: When I was 18-19, I left home. I went as far south as I could go, Key West, and ran outta road. Spent a couple of years there, '70, '72, and got dragged back to western New York. I wanted to do rock & roll and country and couldn't find anyone in New York to do that. Left again in '75 and moved to Austin.

AC: Did you listen to a lot of radio growing up?

GM: I used to fake being sick so I could stay home and listen to the radio. My mom would go shopping, and I'd go to my sister's room, turn her radio on, and twist the dial until I heard something I liked. One day I heard [the Everly Brothers'] "Cathy's Clown." It was like, "That's what I want to do!" It was earth-shattering music to me. Really amazing.

AC: Is that what inspired you to join a band?

GM: When the Beatles came out, everyone started bands, whether you had instruments or not. You'd start the band and worry about the instruments later. People I knew printed up cards in shop class for bands that never had instruments to play.

AC: What was the name of your first band?

GM: The Plague. Played rhythm guitar and sang harmonies.

AC: Who were your country heroes?

GM: I got into pedal steel because of Bob Dylan, he had that pedal steel on "Lay, Lady, Lay." I thought, "I can do that," so I ordered one. When I got it, I decided I better get good, so I played in a really bad country band. I don't remember the name, but I was bad, and they were bad, too.

They gave me records to listen to, though, like Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, and that was amazing! I couldn't believe how good Hank Williams was. It was hick music in my town, no one listened to that, but it hit me hard. Throughout the Seventies, the main thing I was listening to was the Band, Bob Dylan, and Hank Williams.

AC: What was your first experience producing?

GM: I guess it was with Lucinda [Williams]. I was living in L.A. and playing these gigs in Hollywood for $8 a night. I was about to quit and was trying to figure out how to tell her I didn't wanna do it anymore. Before I could tell her, she called up and said, "Good news, we got a record deal! You're producing!"

So I slowly pulled my foot out of my mouth and said, "Yeah, I can do that," even though I'd never really done it before.

AC: Was producing in the plan?

GM: I knew I could do it. I've produced a song here and there, but not a whole album. I figured it was time. I fell into more work after that. It was pretty amazing.

AC: The record company bio says that the press treated your split with Lucinda Williams after Car Wheels on a Gravel Road "with sensitivity." Do you still get asked about it?

GM: They do sometimes. It doesn't do me much good to talk about it. I could say some things.

AC: It says she gave you a gold record for Car Wheels, but you have it sitting out in the toolshed. Is it still that sore a point?

GM: It's been almost six years, which is a really long time. I don't think about it any more. Like I said, I could say some things, but ...

AC: The bio says "Your Picture" is about the split.

GM: It's conjecture. I was never asked about that. It was made up. I never saw that biography before.

AC: She misses you. She told me so.

GM: I'm sure she does.

AC: Who makes music you like?

GM: I like Johnny Dowd, Lonesome Bob, T-Model Ford. I like all the people I work with, Jimmy LaFave, Willis Alan Ramsey, Ray Wylie, Slaid Cleaves ...

AC: There's a very down-to-earth, rootsy spirituality to your music. How do you craft the songs?

GM: When I think about my music, it's kind of blues-based, roots-rock, little bit of country, with an accent on the groove. Then I find a phrase and hack out a couple of verses that don't sound too stupid.

AC: So the music comes before the words?

GM: They come at the same time, but I don't feel like a poet. I don't feel like I'm necessarily saying anything, although I feel like I'm getting better at writing songs. For years I worked with so many great songwriters, I always compared them to these people I worked with, who were great. And I'd go, "Wow, this sucks!"

AC: Anyone who can rhyme "lettin' flies in" with "risin'" has the soul of a poet.

GM: That's one of my favorite rhymes, I was proud of that. On the rest of the album, there's not a rhyme I've thought about since except that one.

AC: What does Fishin' in the Muddy refer to?

GM: Fishin' in the Muddy refers to that ground in between rock & roll and country, that swampy neverland where I feel most of the record is.

AC: Where was the back cover was shot?

GM: That's Lake Travis. On the back, I've got a wild Sixties Italian guitar, then there's a Thirties K-Craft American cheapo guitar. Fishin' in the Muddy is halfway between those two guitars. It's the middle ground. I was hunting for a title and looked at the two guitars, and it came to me.

AC: What's with all the water themes, Toad of Titicaca, Fishin' in the Muddy?

GM: Well, I grew up around the water. Love fishing, love boats, it just made sense to me.

AC: How did you come up with Toad of Titicaca? I went into hysterics as a kid the first time I heard that name.

GM: Jacques Cousteau made a map of the bottom of Lake Titicaca on the border between Peru and Bolivia. It's the world's highest navigable lake and really deep. No one knew how deep it was. He used sonar to map the bottom of the lake, and as he did, he found 2-foot-long underwater toads no one knew existed.

I liked the term "Toad of Titicaca" and jokingly told a friend I was going to name my album that. "You don't have a hair on your ass if you don't do it." So it was kind of a dare.

AC: Or is it just a good, funny word?

GM: It's just a good, funny word. ![]()