Unpardonable

The Bush record of 'compassion' began long before his sojourn in D.C.

By Lucius Lomax, Fri., June 11, 2004

It's conventional among some Texans to say that George W. Bush became more extreme as president than he had been as governor. He didn't try to invade Mexico on his Texas watch, after all. He didn't brazenly curtail civil liberties in the state, nor try to ban abortion, did he? According to bar talk and casual philosophizing, W.'s more extreme tendencies were held in check at the Texas Capitol by the last men standing in the Democratic leadership. With their remaining strength, Texas Dems kept W., people say, from being W. – that is, what we see in the White House, a WASP avenging angel, determined to smite the infidel and right liberal wrongs.

It's an interesting theory – but very difficult to document from the actual Bush record.

Because there was an area of state policy where the then governor plainly made his unyielding intentions known to the world, even from backwater Austin: crime and punishment, especially punishment. A statistic W. left behind from his tenure in Texas is astounding for what it says about his sense of compassion, and also about his apparently limitless moral certainty.

Of 154 capital cases presented to Gov. Bush for possible commutation of sentence, W. sent 151 men and two women to their deaths. In the 154th case, that of serial murderer Henry Lee Lucas, the governor relented only because two attorneys general confirmed that he was on a job in Jacksonville, Fla., when he was supposed to be in Williamson Co. committing the crime for which he was sentenced to die.

It's widely believed but not quite true that W. refused all mercy – every opportunity to grant a commutation – during his six years as governor. In fact, in 20 noncapital cases he granted pardons. (A commutation is the executive limitation of a sentence, usually to prison time already served or, in a capital case, to life imprisonment; a pardon is an official release from a penalty, can be full or conditional, and can occur during or after a sentence has been served.) Most involved relatively minor nonviolent offenses and were early in W.'s tenure in office, before his views hardened – or his national political prospects jelled. (For almost two years after Henry Lee Lucas' commutation, W. didn't sign another.) Three pardons were issued not long before the governor became president. They were not grants of clemency – they involved sexual assaults in which new evidence of actual innocence had been found.

But apart from the Lucas case, there was only one additional commutation – a reduction to time served. The facts of that case might show, when it comes to a question of right and wrong, what it takes to bend W.'s heart.

In this instance, though, the actual wrong was on Gov. Bush's part. He left a woman to languish in prison, years after her sentence was complete.

Shocked Twice

The case originated in Brazos Co., home to Texas A&M – perhaps the single most conservative, law-and-order community in the state. The perp was Sharon Denise Stewart, a 23-year-old black woman from College Station who was busted in the neighboring city of Bryan on New Year's Eve 1992 for trying to sell 1.6 grams of crack cocaine – enough for a good high, but hardly a "major seizure," even by small-town standards.

There was never a question of guilt or innocence. "I had it in my mouth," Stewart said later. "When she [the arresting officer] asked me to open my mouth, I took off running." So did the police. With the assistance of her court-appointed attorney, Stewart pled guilty to possession of a controlled substance and agreed to a 10-year sentence with the provision that she receive "shock probation."

Still in favor in Texas courts, shock probation is one of the brightest ideas of 20th-century American criminal jurisprudence, up there with Miranda rights and stun guns. A first-time offender can be sentenced to a prison term – say 10 years, like Sharon Stewart – and sent to Huntsville, like any other convicted felon. But after 90 days to six months – and in theory, completely unknown to the inmate until that moment – the judge (aware of the plan at sentencing) grants probation. The "shock" is meant to be 90 days of daily life in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, the Texas gulag, after which an inmate theoretically will never break the law again.

Shock probation is not simply disguised leniency, but is considered a good deal for the state – a cost-saving alternative to lengthy incarceration or recidivism. Keeping the inmate in the system any longer than 90 or 180 days is not just additional money from the treasury but, worse, runs the risk of creating a hardened criminal. But partly because of overcrowded prisons, in time the "shock" has degenerated into just another tool of plea bargaining, something to move the docket along, with the defendant knowing before he or she even leaves the courtroom that in a couple of months someone will come to open the cell door. That was the case with Sharon Stewart. Shock probation was part of her plea bargain. It was why she pled guilty.

For Sharon Denise Stewart, the shock was that no one came to let her out.

Pay Her No Mind

We pick up Stewart's case in December of 1994, a year after she had gone to prison. It seems that the judge who sentenced her forgot his promise to get her out.

Learning of his mistake directly from the inmate, but no longer able to rectify it personally, District Judge John Delaney wrote to the Board of Pardons and Paroles to ask that Stewart be set free "as soon as possible." "I make this request because the inmate would have been released from prison on March 3, 1994, on 'shock probation,' but for a mistake made in my office," Delaney wrote. "We failed to take action to suspend further execution of the sentence when I had jurisdiction to do so. Due to the passage of time I no longer have authority to order her release from prison.

"The oversight didn't come to my attention until yesterday when I received a letter from the inmate asking what had happened."

In the meantime, however, Stewart had begun to "act out" in prison. (The record indicates that the beginning of bad behavior coincided with the time Stewart was supposed to be released.) She was transferred from what she considered soft time at the Hobby Unit, near Waco, to a more serious disciplinary stay at the infamous women's prison at Gatesville, north of Austin. The following year she wrote a polite letter, in a clear, well-shaped hand, to the district attorney who had prosecuted her, and explained how she felt she had been wronged by The System.

"I didn't plea bargain to a 10 yr sentence," Stewart insisted. "It was a 90 day shock probation, and I came and did what I was supose to do. after awile I felt like I couldn't trust anyone if I couldn't trust the state" – big mistake – "so I began to do things to get attention. which only got me in trouble. I'm asking that you please look over my case and read the letter the judge wrote and you will understand why I'm asking that you consider me the chance for a time-cut."

The D.A. (longtime Brazos Co. District Attorney Bill Turner, a Democrat) wrote back to Stewart with the bad news that the Board of Pardons and Paroles wouldn't release her until she cleared her disciplinary status. (That refusal apparently led to more acting out.) What followed was a Kafkaesque experience, as Sharon Stewart descended into the state-sponsored hell known as the Texas prison system. Everything she did to be noticed – to remind the state of Texas of its obligation to her – only got her deeper in the hole.

"I gave all my property away," she explained in a recent interview, recalling the end of her "shock time," as she approached what she thought would be release. "I said, 'I'm only here for a 90-day shock probation.' I was good, like the judge said, until my time was up. After that, I didn't care."

No one at the prison knew anything about her being there for only 90 days. The sentence the guards read said 10 years. Time passed and Stewart was put to work on the "hoe squad," chopping the red Brazos River Valley soil, with her only company "just a bunch of bosses on horses with guns, talking about you, talking about your mama.

"Heavy-set girls, guards ask how much you weigh. They tell you, you gonna lose some weight out here." Stewart is a short woman, a little, yes, on the heavy side, with a pretty active mouth on her. She answered the guards back – sometimes discussing the weight of his or her mama – not the way to go in TDCJ, at least not if you want to get out of the sun and escape the hoe squad. "I got so much disciplinary they put me on the 'pay-her-no-mind list.'" Eventually she was transferred to Gatesville, where there is administrative segregation – the infamous "ad-seg," for disciplinary cases.

Dear Governor

As governor, W. denied five commutations and 357 full-pardon requests.

During his term, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles recommended seven commutations and 152 pardons. But in total, during six years in office (January 1995 to December 2000), the governor granted only 21 commutations and pardons.

In fairness to the future president, he was burned once, early in his term in office. In 1995, W.'s first year as governor, on the advice of a Republican legislator outside Dallas, Bush granted a pardon to an Ellis Co. man who had a misdemeanor marijuana conviction. In this case, the clemency recipient wanted to pursue a career in law enforcement, but couldn't be certified as a cop as long as the weed was on his record. Not long after being pardoned, after being commissioned as a constable, he was popped for stealing a handful of cocaine during a drug bust. That's always the fear with pardons and paroles – that someone will get out of jail and commit another crime – leaving the officeholder who granted mercy to take the blame.

But the Stewart case was different because she was not asking for real clemency, for forgiveness, just as she wasn't going to take any shit off guards. She was asking that George W. Bush correct a mistake that everyone in the criminal justice system admitted had been made. In November 1997, after Stewart had been in prison three years, and was finally well-behaved and back on the list for review of her sentence, the Board of Pardons and Paroles voted 17 to 1 to recommend commutation. She had the support of the sentencing judge, the district attorney, the county sheriff, and the police who had arrested her. (A handwritten note by one of the governor's staff, apparently written about the same time, reads, "This lady needs to be out.") The file was sent to Gov. Bush, but the wheels in the governor's office moved slowly, indeed. In February 1999, 16 months later, a lawyer from the governor's office finally called the sentencing judge to ask for information about the case.

In the meantime, Stewart had begun a one-way correspondence with the Texas chief executive. One of her cellmates had a typewriter, and so she alternated between typed and handwritten letters. She had a lot of time to herself in stir, and she did a lot of reading – romances and the Bible – with the result that her grammar and spelling were much improved by the time she adopted W. as her unacknowledged pen pal in Austin.

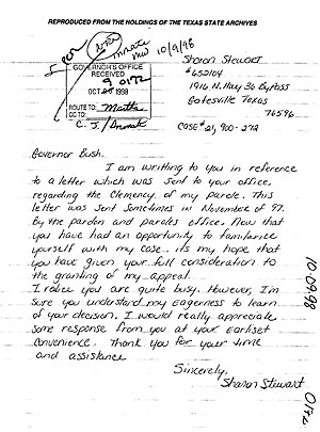

In October 1998, she wrote: "I realize you are quite busy. However, I'm sure you understand my eagerness to learn your decision. I would really appreciate some response from you at your earliest convenience. Thank you for your time and assistance." Actually W. hadn't given her his time or assistance, and apparently wasn't planning to, but in the Big House, hope springs eternal.

The following year, having heard nothing, she wrote again: "Sometime in November '97 the Parole Board wrote to you and recommended a clemency petition. It's my understanding my file has been forwarded to you for final disposition. I hope you've received my file and had the time to review all information and have or will make a decision soon."

In 1999, Idell Stewart, Sharon's mother, telephoned W in Austin. "I called his secretary and told her what happened and she said here it [Sharon's file] is, it's on the bottom of the pile and she said she was going to show it to Bush." A few months later, according to Idell Stewart, her daughter was released.

But W. had nothing to do with it.

Great Expectations

What had been stopping the governor is unclear, although his reluctance to act may have had psychological roots. George W. Bush himself has a drug-using past, when he was "young and irresponsible" as he likes to say – officially alcohol, reportedly harder substances – and since being born-again he has been particularly hard on users and purveyors of narcotics.

There's some support for that theory. There's an unsigned, undated note by a staff member in the Bush files, referring to Stewart, "She's clean but her 2 brothers are known drug dealers," as if family affiliation were enough to keep her in Gatesville forever. Actually her older brother Tommy Ray is halfway through a 45-year sentence for murder, but what that had to do with anything isn't clear either. The Stewarts could be a family of axe murderers and the only issue would still have been whether the state, in the person of George W. Bush, was going to keep the sentencing agreement with the inmate, to right the wrong that everyone agreed had taken place.

But the governor refused to act. The Board of Pardons and Paroles moved unilaterally to release Sharon Stewart on parole on her birthday in 1999. She had been in prison five years longer than her original agreement.

That didn't mean commutation of her sentence was no longer an issue. On Jan. 5, 2000, Judge Delaney wrote to W.'s general counsel, Margaret Wilson, and threatened to out the governor. "Today I am marking my desk calendar on Monday, Jan. 31, 2000. If Ms. Stewart's matter has not been acted on by that time, I will ask the press to make inquiries."

Suddenly, with W. running for president, things began to move in Austin. "It is my recommendation that Ms. Stewart's sentence be commuted for the reason that Ms. Stewart served much more time than she had bargained for in her plea agreement with the state," the general counsel informed W. a week later, repeating the same explanation that the judge had been making for the last five years. "The State should stand by its agreements. In my view, by granting the commutation request the Governor can right a wrong that has been admitted by the judge who presided over Ms. Stewart's case." Even though she was already home by that time, Sharon Stewart was on parole and could still be written up for a violation and returned to prison to finish the 10 years. She had just gotten a traffic ticket for not stopping at a railroad crossing in Bryan, and the police found her without a driver license, a minor affair for anyone except a parolee. In any case, on Jan. 17, after receiving the judge's threat and the general counsel's recommendation, W. signed the commutation later that same day.

"I know I got screwed," Stewart says now, sitting in her apartment in Bryan, waiting to go to work in the laundry of the nursing home where's she's worked for the last four years. "But when you ain't got anybody, what you do?"

"It's impossible for me to know whether the delay by Governor Bush's staff in handling this matter," Judge Delaney, who has since retired, wrote at the time he forced W.'s hand, "is due to insufficient manpower, inefficiency, political timidity, or something else. Whatever the reason, it's a poor example of 'compassionate conservatism.' It doesn't inspire confidence about what to expect from a Bush presidency."

So we were warned about what to expect with W. in the White House. It just seems that nobody was listening. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.