Being Robert McNamara

Through 'The Fog of War,' Errol Morris gets inside a mind full of hindsight, regret, and the lessons of Vietnam

By Marc Savlov, Fri., Feb. 20, 2004

Errol Morris' new documentary, The Fog of War, might just be the most important film in the world right now. Culled from 20-odd hours of interviews with Kennedy- and Johnson-administration Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara – the man widely regarded as the architect of the Vietnam War – the film is broken down into 11 "lessons" drawn from McNamara's crux-of-history lifetime. Among the lessons: "Empathize with your enemy," "To do good you may have to commit evil," "Never say never." That last one is particularly fitting in light of McNamara's 1996 book In Retrospect, viewed by many as a too little, too late mea culpa regarding the author's actions during the Vietnam War.

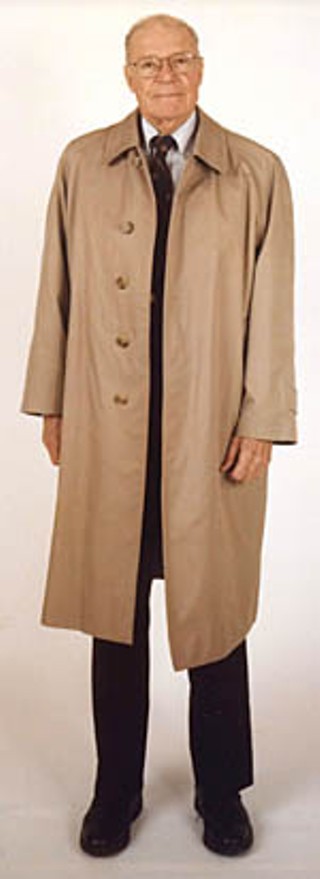

McNamara was 85 in May of 2000 when he began sitting for Morris' questions, but on screen he wears the years well, sitting ramrod straight in a comfortable chair and relating not just his Vietnam experiences, but also those during World War II, during which he served under the super-hawk Curtis LeMay and was partly responsible for devising the fiendishly effective firebombing of some 67 Japanese cities. On one single night in Tokyo, in March 1945, more than 100,000 civilians were immolated.

McNamara never quite apologizes on camera for "McNamara's War," as Vietnam came to be known, but while watching The Fog of War, one senses that – by dint of offering these lessons in warfare and the finer points of how to stay out of war, or at the very least to enter into the crucible with your wits about you – he's doing just that.

The parallels between McNamara's experiences in both World War II and Vietnam and the current administration's bellicose, absolute stance are disturbingly blatant, and watching the former secretary of defense – one of the last surviving members of Camelot's inner circle – speak about the unavoidable strategic errors that arise in times of crisis and the notion that hindsight is a luxury wartime never provides is discouraging when viewed against the current Rumsfeld/Rove template.

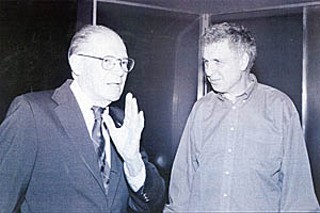

Morris sporadically cuts away from his subject with footage and taped interviews between McNamara and Kennedy, McNamara and Johnson, and battlefield footage, and sets the film to a compelling, melancholy score by Philip Glass [see The Ambience of Existential Dread], which makes The Fog of War all the more powerful, a woeful 95-minute series of lessons that nobody seems to be able to learn.

Austin Chronicle: What was the initial impetus behind Fog of War, and how did you go about approaching McNamara?

Errol Morris: The opportunity to make a movie with one person seemed like it would work in this instance for many reasons. One important reason: The more and more I found out about his story the more and more it became clear it encompassed the significant elements of the 20th century and the photographic record of that history. And there's a photographic record of McNamara, certainly in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

As for approaching him, I just called him and invited him to come up to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I live, and he agreed.

AC: Had you harbored opinions on Mr. McNamara before embarking on this project? Certainly he was as reviled by as many people as anyone in this century. How did you view him previous to Fog of War?

EM: To the extent that I remember clearly, I probably hated him as much as most other people. I describe him in the film as "the man who pulled off the hat trick of being hated by the left, the right, and the center."

AC: What was your initial impression of the man upon first meeting him?

EM: Endlessly fascinating. He's one of the last surviving members of the Kennedy administration, of Camelot, and it's sort of amazing to be connected to history in this way. The stories are remarkable. After all, he was there.

AC: I'm curious to hear what might be in the 18 hours that didn't make it onto the screen.

EM: Some of that will be on the DVD. And on top of all that I've actually continued talking to him since the movie's been finished. It occurred to me that here you have all of these presidential recordings, some of which have just come out in the last year, and no one has gone through them with McNamara. One of the things that we've done is reading through a conversation and then asking McNamara, "What were you trying to say to the president in this conversation, what was the president trying to say to you?" and so on.

AC: Was there anything that McNamara said in his interviews with you that came as a revelation or perhaps caused you to reconsider your line of questioning?

EM: Certainly that remark about being a war criminal with respect to the firebombing of Tokyo was a surprise. A lot of the material about Vietnam was not exactly a surprise, but it did give me reason to believe that the standard interpretation of McNamara and Vietnam is not right. It may not be better, but it's different. You know, I'm struck by comparing the accounts of that time in The Fog of War with the various movies made of these issues. HBO did a TV movie, John Frankenheimer's last film, called Path to War, where Alec Baldwin is playing McNamara. And then there's the film that was made about the Cuban missile crisis, Thirteen Days, and it's interesting. Maybe history is always distorted. Maybe that's one of the things about history, that it's always told from some point of view or with some end purpose in mind. But the Cuban missile crisis in the movie was very much a historical crisis taken out of history. And there's this very curious moment in my own film where I interrupt McNamara – which is very uncharacteristic of me – but I felt some of these instances were necessary. When I say to him, "Well, after all, didn't we try to invade Cuba?" And he seemed somewhat sheepish in his answer: "Yes, of course, and we tried to kill Castro." And then, of course, in Vietnam, these conversations give strong support to the notion that it was not McNamara pushing Johnson into Vietnam but the other way around.

AC: How did your experience of interviewing McNamara impact your notions on the current state of U.S. politics, which are incendiary to say the least, with many striking parallels? And have you looked into screening the film for any members of the Bush administration?

EM: I would love to have this film shown at the White House. I would say that the more successful the film becomes, the more the likelihood that it will be shown, if not in the White House, then possibly to people in the government. And I think it's an instructive film, certainly, for what is going on now. I never intended the film, when I first started to make it, as a commentary on the Bush administration. The first interview was conducted pre-9/11 in May 2001. But the movie has become a very powerful commentary on many of the issues in the Bush administration, such as the silence or puzzling support of Colin Powell with the administration. The question often addressed to McNamara – "Why did you resign?" – seems to have ironic resonance with the question of why Powell lent his name and prestige to what most people believe was something he knew better about. The question of multilateralism, the whole question of the Gulf of Tonkin and imagining an event that took place, which, in fact, never took place. That certainly recalls these WMDs. The McNamara story in The Fog of War is replete with errors, false ideology, confusion, self-deception, wishful thinking, arrogance, and it is sadly ironic that it seems to be happening all over again. Maybe not in exactly the same form, but in a similar fashion as to be clearly recognizable. You know, I've never liked the quote, "Those who are unfamiliar with history are condemned to repeat it," and so I have my own version, which is, "Those who are unfamiliar with history are condemned to repeat it without a sense of ironic futility." And that is the question! I mean, can we learn from anything?

AC: Did your time with McNamara offer up an answer on that one?

EM: I'm something of a pessimist. I don't know. Something has to be done. I'm actually happy that I've made this film. I've never thought of myself as a political filmmaker per se. Quite the contrary. But I'm very glad to have made a political film. I feel that we live in really perilous times and the country has gone off in a direction that is just frightening, and to remain silent and not to speak about these issues seems to me to be wrong. It's one of the arguments that I still have with McNamara, about his reluctance to speak out.

AC: Did you end up discussing 9/11 with him at all?

EM: We haven't really talked that much about 9/11. The attitude toward this current war and the current foreign policies of the U.S. involve themes that are in his books and certainly in this movie. There's one point in the movie where he says that when you can't find countries with similar values to endorse your policies perhaps you should rethink your position. He also tells the story of how we were never able to get the support of the French in our efforts in Vietnam.

AC: We spoke to Philip Glass a while back regarding his work with you and on The Fog of War and I was curious, what was it about his work that initially appealed to you and brought the two of you together? It's a perfect match, him and you.

EM: I remind him, on more difficult moments, that I've been a fan from the very beginning. And I remain a fan. I'm always puzzled by people that say he's just written the same thing over and over again because it seems to me that he's written an extraordinarily diverse amount of music. And he's collaborated with so many, many diverse people, you know, just this amazing list, from Allen Ginsberg to Godfrey Reggio to Martin Scorsese to Twyla Tharp to me.

AC: Can you describe your working relationship with him? Do you hand him the finished film and offer some clue to what sort of tone you're looking for? How does that work?

EM: I edited The Thin Blue Line with scratch music by Philip Glass. I went out and bought a lot of CDs and used the music from Glassworks, from Mishima, from a set of Twyla Tharp dance pieces, and the music worked extraordinarily well, and I was quite worried of what I was going to do to replace the scratch music. How was I going to find someone to write Philip Glass-like music? And then eventually it became, "Will Philip Glass write the music?" There's something very odd about how music combines with film. There's an unpredictable element. I'm always amused when it works as well as it does. I do a lot of commercial work, and people ask me, "What kind of music do you have in mind for this material?" And the truthful answer is I'm not sure until I actually shoot something. And then I put music up against it. Because it's always surprising. Music combines with images in ways that can't always be predicted or, to a certain degree, even anticipated. And I have an additional problem: Unlike traditional movies where you just have a movie scene where music is playing over it, I have these monologues, and the music in many instances is playing over the monologue, and it has to work in such a way that it doesn't destroy the voice, that it doesn't make it impossible for you to listen to what the person is saying but in some very real sense enhances it. So that's always been tricky. From The Thin Blue Line on, and this is now our third collaboration, Philip would write music, and I'll put it in the movie where he intended it to and more often than not it won't work there! So there's a process of shuffling. Shuffling the music from one place to another. And eventually we get a score, but it has always been a struggle, and perhaps this has been the worst struggle of all. However, it's also the best score he's written for me. He did great. It's to be remembered that often it's very, very, very hard even for a composer to predict how his music is going to interact with a movie.

AC: Ultimately what is it that draws you to your documentary subjects? The range of topics you've covered practically defines verisimilitude, but at the same time there are similarities that crop up.

EM: It's usually some kind of mystery, some kind of unresolved question. It's interesting because interviews are human relationships in a laboratory setting. Or something like that. And you're sitting there listening to a person tell a story about themselves in their own words, and there's this enormous mystery: What is inside there? I'm fascinated by factual questions about what really happened, but I'm also fascinated by questions of intent. If you like, the stuff inside people's heads. What was McNamara thinking at these crucial junctures in history? What was going on inside his head?

AC: How reliable do you think his answers to your questions were? Might they not also be fogged or filtered by the passage of time?

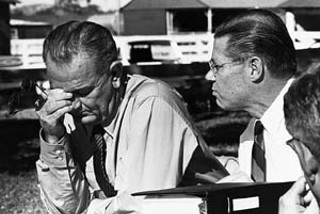

EM: Well, I keep going back over certain kinds of questions. One question that's been asked over and over and over again, is that counterfactual question, "What would Kennedy have done if he had lived? Would there have been half a million ground troops in Vietnam? Would we have bombed the North?" And there's this account that I've heard so many, many, many times, that Johnson was vacillatory and McNamara pushed him into war, that McNamara was the hawk, that it was McNamara's war. One can never know if you take a piece of historical evidence and make too much of it. But I was struck by these two presidential recordings that I put very close to each other in the movie. And they seem to address this issue of intent. McNamara returns with Maxwell Taylor from a trip to Vietnam; he meets with the president on October 2, 1963; and he tells Kennedy that he's in favor of removing advisers. In fact, he's in favor of removing all of the 16,000 advisers currently in Vietnam, and setting a schedule. Kennedy has to run for election in '64; presumably it would be impossible to take the bulk of the advisers out until after the election, but he suggests that they remove 1,000 by the end of '63. And then we find in the national archives all of these newsreels from December – this is after Kennedy's death – showing 1,000 American servicemen boarding planes in Vietnam, coming home, quote unquote, in time for Christmas. Maybe no one will ever know for sure what Kennedy's intent was with regard to Vietnam. And endless amounts of material have been written on this question. To be sure, there are contradictory pieces of evidence, of information. But here you hear McNamara, on a tape, saying to the president, "We need a way to get out of Vietnam and this is a way of doing it." This is what I mean by mystery, by the way.

And then you hear Johnson. The Johnson conversation is extremely powerful to me for a number of reasons. Johnson is chastising McNamara, going back to that October conversation – he makes explicit reference to it – so the two conversations are locked together, for me. Johnson is there lecturing McNamara: "I sat silent and listened while you and the president talked about removing the advisers and I did not agree." And this also goes to intent. So, hopefully, the movie creates this kind of mixture of historical exposition mixed with the denial of certain aspects of history – self-deception, confusion, wishful thinking – set against these pieces of raw historical data. I don't want to make too much of them, but it is the president of the United States of America and McNamara talking in the Oval Office. Or Johnson on a phone in the Oval Office talking to McNamara in the Pentagon. It's that reality, the reality that you feel through the documents and the recordings. Or just finding those documents in the national archives from the firebombing of Japan. McNamara's notes from that time, when you see, in the film, those numbers falling over Tokyo as it burns, those are his actual handwritten numbers from 1945!

AC: I'm wondering if the current administration is keeping similar notes on their military actions.

EM: I don't know. I do think that it's a remarkable and a useful thing that this kind of evidence has been preserved because it is important to see how government works. I sometimes point out that if you're kindly disposed to McNamara, you see some of the things he says as explanations. If you're not so kindly disposed, you see them as excuses. But one thing is absolutely true: There are very few cabinet-level officers who resign and then speak out against the administration. Although ironically such a thing has happened within the last month with Bush's secretary of the treasury, Paul O'Neill! But that's clearly the exception to the rule.

AC: There's obviously a personal risk, career or otherwise, to coming out and speaking out against one's former employers.

EM: Will Paul O'Neill move the policies of this current Bush administration? I somehow think not. After all, you're talking about the weight of this gigantic bureaucracy. It's all very interesting to me. I have talked quite a bit about this issue with McNamara, and McNamara will repeatedly say to me, "Well, I served at the pleasure of the president, he is elected and I was not, and I would never air my disagreements with the president in public." Maybe we need more O'Neills and less McNamaras and Colin Powells. ![]()

The Fog of War opens in Austin on Friday, Feb. 27. Check next week's Film listings for a review and show times.