Naked City

UT neighbors' balancing act

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., Jan. 16, 2004

"The final outcome desired by the majority of ... stakeholders is to create an urban village and true 'uptown' residential district across from the University of Texas while preserving the adjacent historic neighborhoods." That text from the draft of the city's Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan pretty well sums up the grand bargain forged during the yearlong planning process: In return for keeping large-scale student housing and commerce out of the upscale single-family neighborhoods around UT, the city would allow developers to massively increase the density of the core of West Campus.

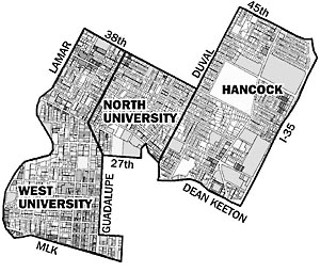

The CACNP, as the name implies, combines three different city planning areas -- West University, North University, and Hancock -- surrounding the UT campus. All have in recent months and years been embroiled in land-use controversies before the City Council -- cases like the Villas on Guadalupe, the Bellmont cottages, and various superduplexes -- that sprang from a common stimulus: the inexorable demand for student housing. For the most part, the neighborhoods have lost before the council, and the lack of an adopted neighborhood plan for these areas (in contrast to Hyde Park or the Eastside neighborhoods adjacent to UT) has been a sore point for their leaders. But the trend of council decisions has also made clear that any draft plan that didn't incorporate a "fair share" of new multifamily infill was going to go nowhere. Hence the CACNP compromise -- lots of new housing and infill, but all in one place.

Elsewhere, the plan aims to recommend downzoning existing multifamily properties, establishing design guidelines, discouraging on-street parking, creating historic-district protections, and otherwise forestalling unwanted change in the combined area's single-family enclaves. North University, in particular, wants to go the whole distance -- creating a "neighborhood conservation combining district," as did Hyde Park, and thus implementing tighter controls on development and redevelopment than are normally possible under city code. The NCCD, says the draft plan text, would "foster the preservation of the neighborhood's original development patterns." Other parts of the plan are more specific about the nature of the threat: One objective calls for neighbors and UT to "develop orientation materials that educate students on how some behaviors adversely affect their neighbors' quality of life."

But in West Campus -- under the terms of a proposed University Neighborhood Overlay -- the current urban fabric, which is already rather dense for Austin standards, could be totally transformed into a district where 15-story buildings are the norm. (Mayor Will Wynn thinks they should be even taller, which existing buildings like Dobie Center and the Castilian actually are.) Within the UNO, auto traffic would be discouraged, streetscapes would be enhanced, and, proponents hope, a real big-city neighborhood will emerge. (One that, according to the plan, may even be occupied "365 days a year" with more than just students.)

This is the exact opposite of what the city has tried to do in West Campus for 20 years, since a 1984 moratorium on high-density development. So far, the nascent opposition to the UNO has come from West Campus property owners who like things as they are -- with an artificial shortage of near-campus housing driving stratospheric rents for low-quality properties, putting students of more typical means way out on the shuttle lines. Several of those owners have announced the formation of a new neighborhood association and their intent to fight the UNO and CACNP tooth and nail. Meanwhile, some of the leaders who've helped craft the CACNP have expressed a converse concern: that City Hall will eagerly embrace the new densities of the UNO and then drag its feet on the subsequent protections for their neighborhoods.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.