What's in a Face?

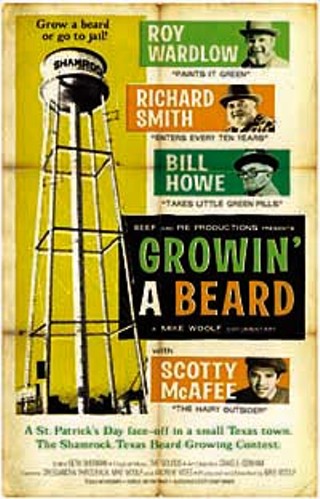

A lot, Mike Woolf discovered while making his short doc 'Growin' a Beard' -- and especially If the face Has got whiskers on the chin and Jowls

By James McWilliams, Fri., Feb. 21, 2003

At the end of the Shamrockers' dirgelike track "Hangman Drums," Kevin Russell erupts into a fumarole of guttural tongue-speak. It's a startling moment. What he emits is nothing short of a primal wail, a hairy crossbreed of a gurgling mountain yodel and a Chickasaw war chant. It's a heart stopper of an eruption, evoking the din of the Earth's core, signifying at once nothing and everything. And yes, I'm talking about Kevin Russell of the Gourds, and you bet I just used the adjective "hairy."

It's apt. The Gourds morphed into the ephemeral Shamrockers to do the soundtrack for Austinite Mike Woolf's short documentary "Growin' a Beard," which follows an annual beard-growing contest in Shamrock, Texas. A Donegal beard-growing contest. The Donegal is, well, here's how the Shamrockers' Jimmy Smith -- voice dripping with brogue -- describes it in the track "Lion's Mane":

There's a beard that's like no other

And here's the reason so

We dispense the whiskers

That grow beneath the nose

The mustache is unwelcome

And what's that all about?

Why who would sweep the kitchen to put the broom beneath his snout?

Right, that's Jimmy Smith, also from the Gourds. And if you still don't get the Donegal business here's a further clarification from Russell:

I got whiskers on my chin and jowls

I got whiskers on my chin and jowls

I got whiskers on my chin and jowls

Got me the Donegal beard

Think Abe Lincoln, a leprechaun, or Captain Ahab. The hipster kids call it an "indie rock beard." In any case, it pleases Woolf to no end that his film is set to music made by men who -- in the follicle department at least -- are especially well-endowed. "They're very much a facial hair-oriented band," he explains, stroking his own trimmed goatee, eyes narrowed in mock contemplation. "Actually, they're just a bunch of hairy hillbillies." Be that as it may, these hairy hillbillies played an unusually influential role in the documentary's production, as Woolf, 33, actually found himself editing his clips around the music that the band generously doled out late one evening at Tequila Mockingbird, an Austin recording studio.

"Kevin saw the film's cuts, told the rest of the Gourds about it, and they all showed up with great stuff -- it's like they were showing up for a test," says Woolf. Which is much more than he has to say about his own preparation as an artist. With characteristic self-deprecation, he sums up making "Growin' a Beard" with this assessment: "I had no clue what I was doing." After compiling 20 hours of footage from the 1997 contest, which he discovered in a generic "off the beaten Texas path" tour book, Woolf picked it up a year ago and began to edit. Based on the tried-and-true premise that "you fuck up, you learn," he first cut everything except the parts where "the camera doesn't shake and the sound was audible." Then (with only a few hours left to trim) he set an ambitious standard for himself, vowing to keep in his film "whatever doesn't suck." Woolf claims to have just recently learned what a tripod was. Like his film -- it's pretty unbelievable.

But back to that unshakable outburst by Russell. After all, it's an especially visceral pump of raw emotion for a feel-good film about a (literally) topical subject. This documentary ostensibly does nothing more than trace the growth of a small town's collective scruff from New Year's Day, when the contestants shave, to St. Patrick's Day, when a randomly chosen judge from the annual Shamrock parade presents the hirsute victor with a smooth plaque. Woolf scoffs at the notion that there's some kind of deeper cultural meaning being explored, some larger point to be examined. "I grew up in Baltimore," he explains. "I just wanted to have fun, I had nothing as big as a theme in mind when I made the film." So then what's with all this heavy growling?

Russell, for his part, recalls that late-night (really, early-morning) recording session, but he can't quite remember from whence the tempest came, much less letting it out. However, at a recent private screening of "Growin' a Beard" at a Tequila Mockingbird studio, he was among the assembled viewers who fell into a rare moment of silence during a helicopter shot of Shamrock -- which is located on old Route 66, about 90 miles east of Amarillo. Woolf steadied his camera (sort of) on the fabled route at the point where it bisects the town. But, with the chopper droning, it's not the intersection that stands out. Instead, one notices a line of traffic streaming down a much newer interstate (Highway 40) and doing a quick jig around Shamrock, evading the town (population 2,200) like tread marks around roadkill. "Shamrock shouldn't exist," Woolf says. "The highway bypassed it -- but not quite enough." With this bypass, its history -- like the history of small-town America in general -- gradually became a last-resort substitute for the present.

For Shamrock, this meant that daily life assumed a bittersweet flavor. Shamrock owes its existence to an old man who lived in a hole and wanted his mail. In 1890, an Irish immigrant sheep rancher named George Nickel built a dugout home and applied to open a post office. Postal officials accepted the application and Nickel evoked the sentimental homeland by naming it Shamrock. Unfortunately, before the post office was built, Nickel's house burned up (not down), he wandered off with his furry flock, and Shamrock had to wait until 1902 to become official. For the next half-century, Shamrock thrived as a plucky incarnation of economic diversity, blending industries such as agriculture, cottonseed oil, gas, and petroleum into a profitable recipe for small-town stability. Declining oil prices and the bypass, however, sapped businesses, shut down industries, and moved services like hotels and restaurants out to the new highway. Reflecting the luck and courage that its name implies, Shamrock hung on into the 1980s with a chemical plant, a nursing home, and a hospital. Today, though, Shamrock is pretty much comatose. While planning a visit to the town, I discovered that several motels that Woolf had frequented back in 1997 were now closed. When I finally managed to call an open motel, the Blarney Inn, the manager and I found ourselves in a Laurel and Hardy routine because the guy thought it was a week earlier than it actually was. "Good thing you didn't ask him what year it was," remarked Woolf.

All of which is to say that any Shamrocker worth his salt would be completely justified in blurting out the occasional tortured moan. Woolf has certainly made a funny film, but he readily acknowledges the town's backdrop of quiet despair. For young people in Shamrock, he says, "there's no reason to stay; as soon as you can get out, you do." Indeed, I had to cancel a weekend trip to Shamrock because a 29-year-old resident had killed himself the day before my scheduled visit. "The entire town knew him of course," Lynn Smith, wife of seasoned contestant Richard Smith, explained over the phone. "Plus," she continued, "I've got a backhoe stuck in my yard and Richard's getting a kidney removed -- you'd better stay home." Not exactly the ideal context to be asking people questions about facial hair. Woolf was saddened upon hearing this news, but wondered just what a 29-year-old was doing there in the first place.

For the urban sophisticate, the old folks of Shamrock might seem like mockable material, not unlike the Michigan yokels skewered throughout Michael Moore's Roger and Me. But here is where "Growin' a Beard" differs -- and flourishes. Woolf's genuine sensitivity to the plight of Main Street America manifests itself in a sweet kind of humor that never condescends and, instead, reveals an honest appreciation of the film's subjects. It's as if whatever goodness the town has lost over the years has been preserved in the warm hearts of its citizenry. Woolf captures that warmth without maudlin affection or ironic distance. "He didn't paint these guys as bumpkins," says Scotty McAfee, the film's "hairy outsider" who traveled from his home in Austin to participate in the St. Patrick's Day judgment. "These people graciously let me into their homes," explains Woolf. "They all thought I was crazy. I mean, I'm coming into their house, setting up a tripod in the bathtub, and asking them about their beard. This is a town of 2,000 people. It's not normal. You look back, and you wonder, 'What was I doing in a tub watching a strange man shave?' You can't dwell on that." Then he dwells on it and says, "But they welcomed me."

And he welcomed them. In a sense, Shamrock's St. Patrick's Day parade was a custom-made cultural piece for Woolf's idiosyncratic professional puzzle. He studied communications at Boston University, where he recalls answering test questions about Tony the Tiger. His education, he explains, "was not a real thing. It should not be allowed." During a short visit to his hometown of Baltimore, where Woolf was raised on a steady diet of John Waters, he shot (with a camcorder) his friend participating in a Polish-sausage-eating contest, an event capped with an award ceremony presided over by Art Donovan. After taking a job in Austin writing commercials for GSD&M in 1994, Woolf made a short film of his same friend participating in the annual Spam Cram, a choice piece of cinéma vérité whose dramatic denouement consists of the hapless gentleman puking into a plastic cup. By these standards, a beard-growing contest seemed downright ho-hum, but definitely worth a look into.

"Real situations involving real people" is what ultimately pulls Woolf to events like the Donegal contest. It just so happens that the real people Woolf stumbled upon in Shamrock are men like Richard Smith, the town's normally smooth-faced "chief fuzzer." Smith has entered the contest -- and won -- every 10 years since 1958. He limits his participation to once a decade in order "to give everyone else a chance," and owes much of his success to a strict vitamin regimen and the fact that his beard has gradually turned from jet black to stark white over the last forty years, lending it an aura of sagacity and unpredictability. With misty admiration, Woolf says of Smith, "He just grows a strong beard, plain and simple -- big, full, thick -- he has history on his side." Or Roy Wardlow, another regular contestant who always tries a new gambit, such as a tasteful green stripe down the center of his well-set Donegal. "You never know what he'll bring to the party," says Woolf. Then there's Bill Howe, editor in chief of the Shamrock Texan and a man never seen wearing anything but a bright green jumpsuit. On any given St. Patrick's Day, Howe can be found with a pale green Donegal beard. Strange thing is, the hair really appears to be green. No paint, no roots betraying a dye job. "He takes little green pills from Ireland that make his hair turn green," Woolf explains, a bit too matter-of-factly.

Not least, there's Scotty McAfee, the Austin participant cajoled by Woolf to grow the Donegal and participate in the 1997 contest. Why McAfee? "First of all," Woolf explains before his private screening, "he's Irish-Lebanese. And you have to give him credit." He continues. "The man grows hair at an exaggerated rate. It's not unnoticed. After four days his face is a conversation piece." McAfee described his experience as something akin to "joining a fraternity" or "drinking out of the same whiskey bottle." After watching a younger and slightly thinner version of himself on screen, he says, "I don't remember being that clever." To wit: As Woolf films McAfee shaving his upper lip the night before judgment day, McAfee hacks away at the black thatch covering his face and remarks, "It's like chopping down the Muir Woods with a Weed Eater."

After the screening, the crowd buzzes around Tequila Mockingbird under the impression that they've just seen something remarkable. Funny as hell, for sure, but something more. Woolf announces to his staff that the film has officially been accepted to SXSW. People are obviously thrilled. Seth Sherman, the film's editor, seems stunned. Woolf rushes around, saying hello and thanking everyone for one favor or other. Someone makes a joke about a ponytail-growing contest. Several men consider aloud the possibility of entering next year's Donegal contest. Woolf says something to me about truth being better than anything you could ever make up. Then, after filling his mug with Guinness beer, he takes a frothy gulp and says that he can't wait for Shamrock to see the film he made for them. ![]()

"Growin' a Beard" will screen at Symphony Square (1101 Red River) on March 10 at 7:30pm. Admission is $1. The Gourds will perform live after the film.

The film will also screen during the SXSW Film Festival on March 8 11am, at the Convention Center; March 12, 3pm, at the Hideout, and March 15, 1:30pm, at the Alamo Drafthouse Downtown.