Can Lazarus Rise Again?

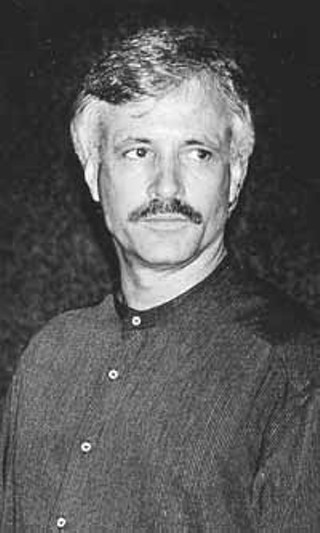

Will Gary "Bankrupt" Bradley live to fight -- and spend -- another day?

By Amy Smith, Fri., Oct. 11, 2002

Until just a few weeks ago, the more cynical folks keeping tabs on Gary Bradley's bankruptcy were giving odds that the high-rolling developer would coast through the process, win a dismissal of his $73 million debt to the taxpayers, and be back in action the very next day. End of story.

Then came a bolt from the blue. Last month, a Travis County family law judge delivered a startling ruling in response to Bradley's request to reduce his $4,000 per month child support payments. Not only did Associate Judge John Hathaway deny the motion, he candidly explained the factor that weighed most heavily in his decision: the mysterious Lazarus Exempt Trust -- the Rubik's Cube of Bradley's bankruptcy that's keeping various lawyers up at night. Bradley's sister Kay Bradley Hulse established the trust two years ago, naming her only sibling, Gary, as the sole beneficiary, and a cousin, Brad Beutel, as the trustee. The total value of the trust is uncertain, but in Judge Hathaway's account of Beutel's testimony, the seemingly impenetrable treasure chest is "land rich, cash poor," and its handlers aim to sell the land in order to make the trust as "liquid as possible." As Hathaway noted, the trust owns about 1,800 acres of land worth $32 million, and a number of business entities.

Though Bradley claims no control over the trust or its entities, the trust nevertheless serves as Bradley's personal savings and loan, the judge found -- an S&L which the developer repays "if at all, at some uncertain, unspoken time in the future ..."

Hathaway's transcribed ruling -- played on page one of the Statesman the day after its filing in district court -- jolted Bradley's creditors awake. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., for one, suddenly took a renewed interest in collecting on the developer's debt to U.S. taxpayers, who have borne the brunt of Bradley's failed loans. In 1995, the federal courts levied a $53 million judgment against Bradley, and with accrued interest the debt has since grown to $73.5 million.

The key question now is whether the state court ruling -- that Bradley has ready access to his sister's trust for the purposes of child support -- is also strong enough to pierce Lazarus in federal bankruptcy court in order to pay the developer's creditors.

All eyes are on the characteristically tight-lipped FDIC, as the agency weighs its next move. The current deadline for filing objections to a discharge of Bradley's debt is Oct. 15 -- also Bradley's 54th birthday. Because of the complexity of the case, bankruptcy trustee Ronald Ingalls has filed a motion to extend the deadline for 60 days. The judge has scheduled a hearing on Oct. 16 to consider the motion. Bradley's attorney, Stephen Roberts, says he'll oppose the motion. "There's been plenty of depositions and he's given [the FDIC] all the information they've asked for," he said. "I'll tell you, in my 20 years of doing bankruptcy cases, I've never had anyone ask for an extension."

But cases like Bradley's don't arise all that often, so Ingalls recently recruited additional help -- Austin bankruptcy attorney Pat Hargadon -- to help unravel the labyrinthine details of Bradley's finances. And in the wake of Hathaway's ruling, the FDIC has also told trustee Ingalls it wants to schedule another deposition with Bradley, although Roberts says no one from the agency has contacted him in that regard.

During a two-day deposition in May -- arranged after some prodding by U.S. Congressman Lloyd Doggett at the behest of the Save Our Springs Alliance -- federal lawyers questioned Bradley extensively about his finances. But the feds' pursuit of Bradley was short-lived; the mission sputtered to a stop in July when Bradley filed under Chapter 7 of the bankruptcy code. In his filings, Bradley claims $500,000 in assets, $136,000 of which is exempt from creditors. He lists debts totaling almost $78 million, with $73.5 million owed the FDIC, and nearly $4 million owed the IRS. Six remaining creditors include his ex-wife and the Lazarus Trust, which Bradley's filings show he owes $270,000 (see "Bradley's Creditors," p.28).

Bankruptcy trustee Ingalls says that while Hathaway's ruling provided more information to work with, it wasn't necessarily specific enough to be applied in the bankruptcy case. In most cases, he said, "if there's one court that decides an issue, then all future courts can rely on that decision. But what the judge ruled is that Bradley has enough access to the trust [to pay the additional child support]. That's not the same as saying [Lazarus] is an invalid trust" -- meaning more evidence is needed to justify cracking the trust and disbursing its assets. Trusts are typically untouchable in bankruptcy cases -- unless there is overwhelming evidence showing that the assets of the trust are indeed the debtor's assets.

Beyond that issue, an equally formidable challenge would arise if the FDIC moves to object to the debt dismissal to recoup some of taxpayers' money. The feds would have to produce evidence that Bradley committed fraud in connection with $100 million in loans that he and partner James Gressett secured from Gibraltar Savings Association in 1985 to develop the Circle C Ranch -- Bradley's most visible imprint on Austin. The institution that succeeded Gibraltar after its collapse in the S&L crisis tried a similar strategy when Gressett filed for bankruptcy in 1994 (see "Gibraltar v. Bradley," p.26).

Despite widespread speculation that Lazarus serves as a safe house for Bradley's assets, there is thus far no hard evidence. The speculation is understandable; the trust, its entities, and other Bradley-affiliated businesses all bear the same address as the developer's office -- 1111 W. 11th -- where a 132-year-old turreted structure perches atop a hill in regal splendor. Originally built for the Texas Military Institute, to Bradley and his associates it is simply "the Castle." Though some observers suspect that Bradley controls the trust and its many tentacles -- and Bradley's name inevitably appears prominently in news reports on the various projects supposedly underwritten by the trust -- his name does not appear as legal owner of any of the trust's assets.

Bradley agreed to be interviewed for this story only via e-mail, and even in writing, Bradley is vehement on the subject of the trust: "I have not hidden money, set up offshore accounts ... and I didn't establish a trust," he insists. "My sister created a trust for me a couple of years ago. She is my only sibling and we are very close. If the purpose of the trust was to hide assets, and I was the type of person who would consider doing such a thing, then I think it would be reasonable to assume that I would have done it 10 years ago."

Eric Taube, the attorney for the trust, echoes his client. "People think it's somehow inappropriate to create a trust for someone without something sinister going on," Taube said. "No one has been able to identify any assets that Gary ever had -- no one has ever come close to it." One bankruptcy attorney familiar with Bradley's case agrees that Lazarus will be tough to crack. "When you see transfers going into a trust and coming out of the trust, it doesn't mean something is wrong, it just raises a lot of questions." In the end, the lawyer predicted, Bradley will pull through just as he always does. "There's a lot of chatter out there about what's going to happen with him, but I think he'll survive -- because he's a survivor."

Whatever ruling Judge Monroe makes, said trustee Ingalls, "he's not going to hammer Bradley just because he's Gary Bradley, and he's not going to go easy on him just because he's Gary Bradley."

Lifestyle of the Bankrupt and Famous

The 23-page transcript of Hathaway's ruling, delivered from the bench, reads like a folksy Mark Twain oration on wealth and the moral obligations of parenthood. "Some in the community might be amazed, be bewildered, be disgusted that you would spend tens of thousands of dollars fighting over $1,500 versus $4,000 a month in child support," Hathaway observed, "when many people in the community don't have a net income of $1,500 or $4,000 to spend on children, much less one child."

Based on testimony and evidence gleaned from about 90 boxes stuffed with assorted papers that Bradley submitted in the discovery process, the judge flatly rejected the flamboyant developer's claim of financial hardship. He did, however, rule that both Bradley and former wife Lisa are good parents. "And the proof is in the pudding," he told them, "and that is your son." Nevertheless, Hathaway found no reason to reduce the support payments, particularly when Bradley himself lives quite comfortably on loans, advances, and other perks he receives from Lazarus and its entities, as well as from his employer of record, Castle Hill Realty Management, where he makes $12,000 month as a consultant, or dealmaker. According to testimony in the bankruptcy proceedings, despite his official penury, Bradley has also been able to lavish his fiancée with expensive gifts -- a $60,000 engagement ring here, a $19,000 pair of earrings there, and, for whatever reason in Texas, a chinchilla coat.

Testimony also showed that Bradley's sister pays $1,000 to $2,000 a month for Bradley's "medicinal supplements," and that Lazarus Investments, an entity of the trust, is letting him slide on the rent at one of its residential properties -- a $1 million swankienda in Pemberton Heights. At a May hearing, the court learned that Bradley has sufficient income for personal training sessions as well as weekly facials and massages. Statements for these luxuries are mailed to his office, and the bills get paid. Remarkably, Bradley says he doesn't know whether those bills are paid from his personal account or someone else's.

Considering that these cumulative expenses far outweigh the balance in Bradley's personal bank account, Hathaway concluded that the developer has a pretty good life. The current monthly child support payments of $4,000, plus an additional $2,200 for extracurricular activities, might seem extravagant for a 9-year-old boy -- and Ted Terry, a prominent divorce lawyer who is representing Bradley's ex-wife -- agrees. But, he said, "those are the [legally] proven needs of this child. That's not every kid's proven need, but Gary agreed to that amount in 1999 [when the divorce was finalized]. Gary wants to maintain the same lifestyle he had in 1999, but he shouldn't do it on the back of his child -- that just doesn't fly at the Travis County Courthouse. His house of cards fell apart completely in front of Judge Hathaway."

Bradley, on the other hand, argues that his support payments for his son are also subsidizing his ex-wife's expensive tastes. "I obviously did not agree with Judge Hathaway's ruling," he wrote, "but as Chevy Chase might say, 'He's the judge and I am not.' I will do whatever it takes to meet the needs of my son, but I no longer want to pay for my ex-wife's lifestyle. Even if I knew the money was going directly for my son's benefit, I would not want $5,000 to $10,000 a month spent on a 9-year-old boy. I do not want him spoiled. I want him to understand the challenges and hardships that most people face every day. In other words, I want him to grow up in the real world."

Enemies and --

Austin environmentalists, who have fought Bradley over his development projects since the early Eighties, have maintained a keen interest in the case. Said Brad Rockwell, deputy director for SOS: "Unless the FDIC does a thorough investigation and determines that Bradley has not committed fraud, and that there is no basis for the pleadings that accused Bradley of fraud, the FDIC should make the same objections to discharge that were made against Gressett." The fact that the agency has historically dragged its feet on the issue, he said, "leads us to be concerned that the FDIC will let Bradley off the hook, at the taxpayers' expense."

Bradley and SOS have been at each other's throats for years, and Bradley professes little fondness for Bill Bunch, the group's executive director. Bunch, says Bradley, "would definitely meet my definition of a bully. Like most bullies, he is also a liar and a coward." In an e-mailed response, Bunch wrote, "I'll gladly stand on my public record of integrity. At the same time, I would say that the public record is abundantly clear that Bradley is a liar and a fraud, [and] morally bankrupt...."

Less publicly vocal are the surprising numbers of people -- many of them lawyers and politicians -- who are gleefully watching from the sidelines. Bradley has made many enemies as he's climbed his way to the top, fallen, climbed again, and so forth. His whole life has been marked by a series of sharp ups and downs; more so, it seems, than even the cyclical nature of his business. There are others who have stuck by him over the years, and at least some who have profited from that relationship -- although at the moment it's a bit difficult to locate Bradley's defenders. When the Chronicle contacted three prominent players in the real estate community seeking comment on Bradley, two didn't return the phone call while a third -- Kirk Rudy, president of the Real Estate Council of Austin -- had his assistant call back to say that he doesn't know Bradley all that well and he couldn't think of anyone else who did. "An interesting aspect of filing bankruptcy is you definitely find out who your friends are," Bradley said. "It may be the most important thing I have learned from this experience."

Trust Me

Yet the child support and bankruptcy cases confirm that Bradley, for all of his woe-is-me refrain, enjoys the richness of life in the fast lane. He may be broke, but he still has eight suits, 40 shirts, 15 pairs of shoes, 33 ties, $7,000 worth of accessories -- watches, rings, cuff links, and belt buckles -- and collectors' copies of both gold and platinum records of the Beatles' Hey Jude album. He may be broke, but judging at least from Bradley's extravagant gifts, his fiancée hasn't yet felt the pinch. "Gary is between a rock and a hard place when it comes to explaining his financial situation," Terry said. "I'm thinking he's got a lot of explaining to do."

Bradley says he's being unfairly attacked for a bankruptcy which, he believes, would not have drawn nearly as much attention had he filed when every other developer in town was throwing in the towel. "Name me one developer that was active in Austin, Texas in the 1980s who borrowed over $1 million and repaid all of his loans," Bradley challenged. "If [Tony] Sanchez can stiff the taxpayer for $161 million ... yet he is worth hundreds of millions of dollars and can waste $75 million running for governor, as opposed to paying the $161 million debt that most people would say he owes the taxpayer, tell me what you really think about that and how it compares to my situation." Bradley, referring to the bailout of Sanchez's Tesoro Savings & Loan, may have a point about the Democratic candidate for governor -- but it's qualified by Bradley's own close friendship with incumbent Gov. Rick Perry, a friendship that resulted in Perry's enrichment on a real estate deal that began with a tip from Bradley.

Through the years of ups and downs, Bradley has maintained political friends of every stripe -- including prominent Democrats and Republicans -- at least in part because he's always spread around plenty of the most important political commodity: ready campaign cash. It's partly that benevolent history that has political onlookers predicting that whatever happens in the courts, Bradley will come out financially smelling like -- perhaps not roses, but certainly not like stinkweed.

Lazarus, Phoenix, Alien --

Gary Bradley wasn't born rich, but says he vowed early on that he'd make his first million by the time he was 30. And he did. Texas Monthly's Gary Cartwright recounted Bradley's rags to riches story in May 1984, shortly before Bradley and James Gressett bought nearly 20% of the Houston Rockets. Years before the article ran, Bradley had already become a media lightning rod, a bane of environmentalists, and friend or foe of seemingly every mover and shaker in town. He was rich, handsome, daring -- and he always got the girl. John Wooley, the CEO of Schlotzsky's and Bradley's former partner in the West Austin Rob Roy development, told Cartwright, "He had a James Dean image. It was a dominating theme in his life -- fast cars, women, flash."

In 1979, reported Cartwright, Bradley teetered on the brink of ruin -- then hit the jackpot. The proposed Rob Roy residential community was running up against stiff opposition from city staff and environmentalists, and he and Wooley were deep in debt from trying to get the project off the ground. The stress took such a toll on Bradley that he ended up in the hospital "puking blood," and nearly despaired of his million-dollar deadline -- he was only months away from turning 31. When he recovered, Bradley borrowed $15,000 and gave it to the University Baptist Church, whose pastor was Rev. Gerald Mann (more recently renowned as the preacher who prayed with President Clinton the day he apologized for the Monica Lewinsky scandal). Mann told Texas Monthly that Bradley "promised the Lord that if he became successful, he wouldn't forget Him. Then he handed me the envelope."

A few weeks later, the City Council overruled staff recommendations on Rob Roy and approved the project. Yet Bradley and Wooley still needed to sell the lots before they could build. Along came yet another divine intervention: white flight. When word spread that the Austin school district was about to begin busing students for desegregation, many white homebuyers headed west -- to the Eanes School District and to Rob Roy. According to Cartwright, Bradley and Wooley sold 100 lots in 30 days. Since then, Rev. Mann and his Riverbend Church -- now interdenominationally located out on Loop 360 at the Colorado River -- have continued to reap the rewards of Bradley's success. His bankruptcy filings list his most recent contribution to Riverbend on Oct. 1 of last year: the considerably less princely sum of $575.

Bradley's instincts for financial survival -- indeed virtual reincarnation -- are explicitly reflected in the names of his sister's trust and his companies: "Lazarus" (who at Christ's command rose from the dead); "Phoenix" (the mythical bird that rises from its own ashes); and "Alien," after the unkillable outer-space monster in the blockbuster Hollywood film trilogy. During an August bankruptcy hearing, Bradley drew guffaws when he recalled how he selected that name: "I saw that monster ... could survive in any environment and I thought I would, but I didn't, so there won't be an Alien II."

That particular testimony also reflects the opposite aspect of Bradley's character: his reflexive self-pity when his affairs are going badly. Each time he publicly stumbles, he laments his fate, points fingers at his detractors, and wonders why such terrible things happen to him. But each and every time -- thus far -- he has also risen from the dead. That's why so few observers are betting that this time Bradley's down for the count. It's true that the script for the current sequel features really heavy artillery -- the federal government -- but front-row critics are already pointing out that if the FDIC hasn't tried diligently to recoup the taxpayers' losses in the last six years, why should anyone expect the agency will now go the distance to prove fraud against Bradley? One insider suggests that at worst, the FDIC will seek a settlement -- for how much, and from where, one can only guess.

Will Lazarus rise again? Can the indestructible Alien return for one more sequel? Those who think otherwise might recall the 30-year-old debtor who, as promised, became a 31-year-old millionaire. Asked to make his own judgment, Bradley responded, "I guess you might say that I am a compulsive finisher. To me there is nothing more rewarding than to have a vision or goal and to complete it exactly as it was originally envisioned." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.