Serve Chilled

The Summer Reading Menu

By Rebecca Chastenet dé Gery, Fri., Aug. 3, 2001

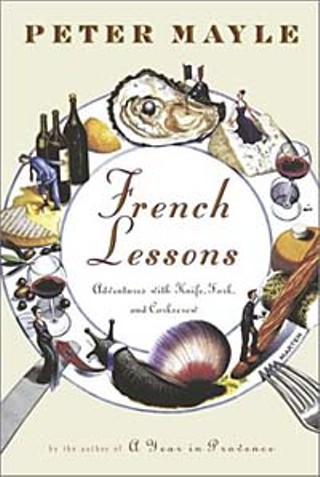

French Lessons

Adventures With Knife, Fork, and Corkscrewby Peter Mayle

Knopf, 256 pp., $24

The French have a love-hate relationship with Peter Mayle, the British-born, French-resident author of the bestselling books A Year in Provence, Toujours Provence, and Encore Provence. As a general rule, they love that Mayle loves France and that through his hefty book sales, he has kept the dream of France alive for millions of other less-traveled souls. What they don't love -- indeed complain about vociferously -- is Mayle's frequently condescending tone when describing French life and customs.

American readers, of course, have gobbled up Mayle's books with as much avarice as their British counterparts, regarding the passages that most French find offending as enjoyably accurate, often comic descriptions of the "quaint," curious ways of the French.

If Mayle hadn't stirred up enough controversy already, his latest book, French Lessons, assures plenty of cross-cultural sparring. The book delves into the subject closest to French hearts: Food.

In French Lessons: Adventures With Knife, Fork, and Corkscrew, Mayle travels far beyond his adopted home of Provence, serving up tales of small-town food fairs, fraternal orders dedicated to food, and outrageous meals at out-of-the-way restaurants. He even dedicates a chapter to demystifying France's revered Michelin Guide, and in another, attempts to explain "the Inner Frenchman," whom he credits with an innate appreciation for fine food.

Mayle opens the book with the admission that he first ate -- really ate -- in France as a young man. Because Mayle never claims to be an authority on food, much less French food, French Lessons reads like a tasty travelogue, not a cookbook or gastronomical journal. In most cases, the author has done his homework. Foodies and Francophiles will enjoy Mayle's take on the increasingly famous messe des truffes (Mass for Truffles) held annually in the village of Richerenches, his discovery of the blue-footed Poulet de Bresse, and the story of his official initiation into the Brotherhood of the Frog Leg Tasters of Vittel.

Occasionally, Mayle gets things wrong. For example, he erroneously says the top-of-the-line sea salt known as fleur de sel comes exclusively from France's Camargue region. (It is harvested in all sea salt-producing regions and is the result of a particular set of climatological conditions.) But what the book occasionally lacks in accuracy, it makes up for with atmosphere.

Mayle is at his best when describing the people and circumstances surrounding French foods. There's the man who instructs him on the finer points of escargot eating, the Japanese woman competing for the title of the biggest eater of Livarot cheese, and the half-dressed crowd at Club 55 near St. Tropez.

My favorite chapter covers the 16-year-old Marathon du Medoc, a marathon through Bordeaux's finest vineyards dotted with wine tasting stations for the runners along the way. In fact, I just may have to go into training to get a taste of the 15,000 oysters, 900 pounds of entrecote (steak), and 350 pounds of cheese paired with some of the world's finest wines.

Although I began French Lessons prepared to be slightly annoyed, I found myself increasingly absorbed by it. The stories are as delicious as can be, and they did indeed get me dreaming. Tuck the book into your beach bag. It's light and lively -- a scrumptious little vacation in itself.